The Long Arm of Authoritarianism: Possibilities for Repression and Opportunities for Change

By Katherine Armstrong ’20

For most of my life, I thought of migration as possibility. The possibility to live, work, put down roots, and prosper in a new country. I learned and thought about the ways that host countries restrict immigration or make immigrants feel unwelcome. Yet it wasn’t until I read Tsourapas’ piece, “A Tightening Grip Abroad,” that I recognized sending states’ capacity to negatively shape emigrants’ experiences long after they leave. In today’s world of social media and smartphones, sending states have infinite possibilities to control and silence dissidence within their emigrant communities.

This practice is known as transnational repression. You have likely heard of some examples, even if not by name. The murder of Jamal Khashoggi, threats against Uyghurs’ relatives in China, and hacking of Iranian-American social media accounts are some of the most well-known instances, but they represent only the tip of an iceberg. In the early stages of my research, I was struck by the limited scope of scholars’ and practitioners’ discussions of transnational repression. Most importantly, what are the consequences for U.S. security and how can these be mitigated through U.S. policies? I endeavored to answer these questions as a research fellow with the Project on International Peace and Security (PIPS).

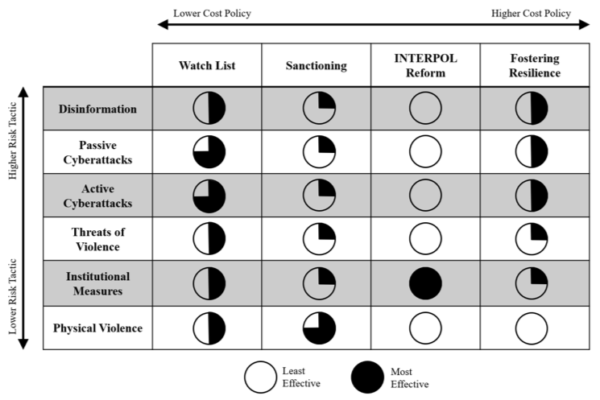

I began by thoroughly examining this modern phenomenon, from its historical precedents to its current manifestations. I catalogued and categorized incidents of transnational repression. I encountered six primary types: disinformation, passive cyberattacks, active cyberattacks, institutional measures, threats of violence, and physical violence. Dividing non-democracies’ repressive toolkit into categories made it easier to understand why tactics posed different levels of risk and could be addressed by various policies.

A key distinction among the tactics is that the first three are technology-based, while the second three are technology-enabled. Technologies that created opportunities for repression—especially smartphones and social media—not only reshaped the toolkit, but also made the tools more dangerous to host countries like the United States. Tech-based tactics are affordable, effective over long distances, and difficult to attribute. They are easy to use against targets outside of emigrant communities, something that we already observe in attacks against journalists and NATO personnel. The toolkit of transnational repression threatens our national security: non-democratic regimes are learning to exercise control across borders over military servicemembers, intelligence agents, politicians, and civil society leaders.

Fortunately, there is a framework in place that could combat this threat, including individual sanctioning and INTERPOL reform. Yet I want to highlight the most novel and, I believe, the most efficient component of my proposal—a watch list of victims (confidential) and perpetrators (public). The watch list would centralize existing information collection and provide educational cybersecurity resources to targets. Modeled after indices such as the Freedom in the World project, it would hold perpetrators accountable and act as a decision-making tool for politicians and practitioners.

I began my research disheartened by the seemingly endless possibilities for repression. I concluded it, however, hopeful about the opportunities for the U.S. government, NGOs, and multilateral organizations to make a difference in the lives of migrants across the world.

Read Katherine Armstrong’s full findings in her white paper (pdf) or watch her video briefing.

For more information on the Project on International Peace and Security visit the GRI website.

No comments.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.