Power-washing the Paleozoic Petersburg Pluton

300 million years ago, vast quantities of magma intruded the Earth’s crust deep beneath what would one day become Richmond, Virginia. The magma that reached the surface fed a legion of volcanoes which no doubt erupted their fiery wrath over Ol’ Virginny, but much of that magma crystallized at depth, forming granite with its distinctive constituents of coarse-grained feldspar and quartz. The volcanoes have long since been eroded away, but the granite remains and geologists know it as the Petersburg Granite. The Petersburg Granite forms the bedrock over a large area in east-central Virginia, and one of the best places to see it is along the James River in Richmond.

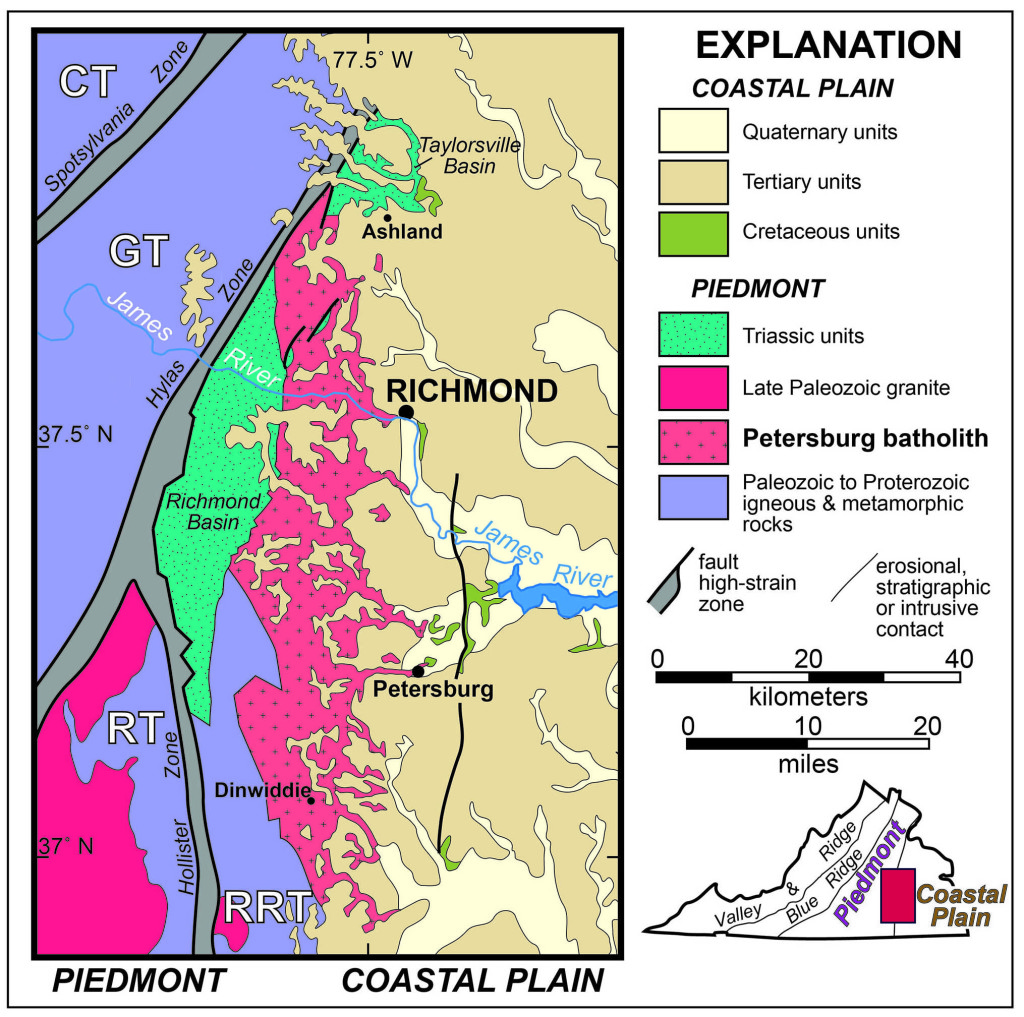

Generalized geologic map of the Petersburg batholith in east-central Virginia. CT- Chopawamsic terrane, GT- Goochland terrane, RT- Raleigh terrane, RRT- Roanoke Rapids terrane. Modified from Owens, B.E., Carter, M., and Bailey, C.M., 2017, Geology of the Petersburg batholith, eastern Piedmont, Virginia, in Bailey, C.M., and Jaye, S., eds., From the Blue Ridge to the Beach: Geological Field Excursions across Virginia: Geological Society of America Field Guide 47, p. 123–133. doi:10.1130/2017.0047(06)

The Earth’s surface is a complicated place, as some surface processes erode and remove material (collectively we’ll call these processes Pe), whereas other processes weather, alter, and cover materials (these we’ll call these Pc). When Pe > Pc, bedrock is exposed at the surface, but when Pe < Pc the bedrock is covered and commonly mantled by sediment, soil, and/or saprolite.

In eastern North America, Pc typically routs Pe, and the Earth’s surface is cloaked in soil, typically with vegetation growing out of it. However, the waters of the James River, as they dash towards sea-level in the Fall Zone at Richmond, are effective agents of erosion exposing acres of bedrock in the channel. Year-after-year we take William & Mary geology students to the south side of Belle Isle to see and feel the Petersburg Granite, because it’s an exceptional spot to learn about deep Earth processes as the rocks are so well exposed.

Expansive outcrops of Petersburg Granite exposed in the old channel of the James River, south of Belle Isle.

But there is a problem: over the past 10 to 15 years, the outcrops exposed on the south side of Belle Isle have lost some of their luster. In many cases these classic exposures have been covered; at some locations there’s a patina of graffiti or earth-tone paint (ironically used to cover the graffiti), while at other locations it’s a veneer of sediment or a Fe- and Mn-oxide coating produced by cyanobacteria. The James River is the geologist’s tricky friend as the river creates the bedrock outcrops, but also covers outcrops with the detritus it transports and then deposits. In the past decade, high-flow events (floods) have not been vigorous enough to wash away the grimy silty-sand that clings to low outcrops.

On Sunday, we decided to do something about this problem; we bolstered Pe by taking matters into our own hands. More precisely, we put a power-washer into our own hands and cleaned up a few of the outcrops at Belle Isle.

William & Mary geology major Tyler Skelton power-washing an outcrop, Professor Brent Owens works on his managerial skills.

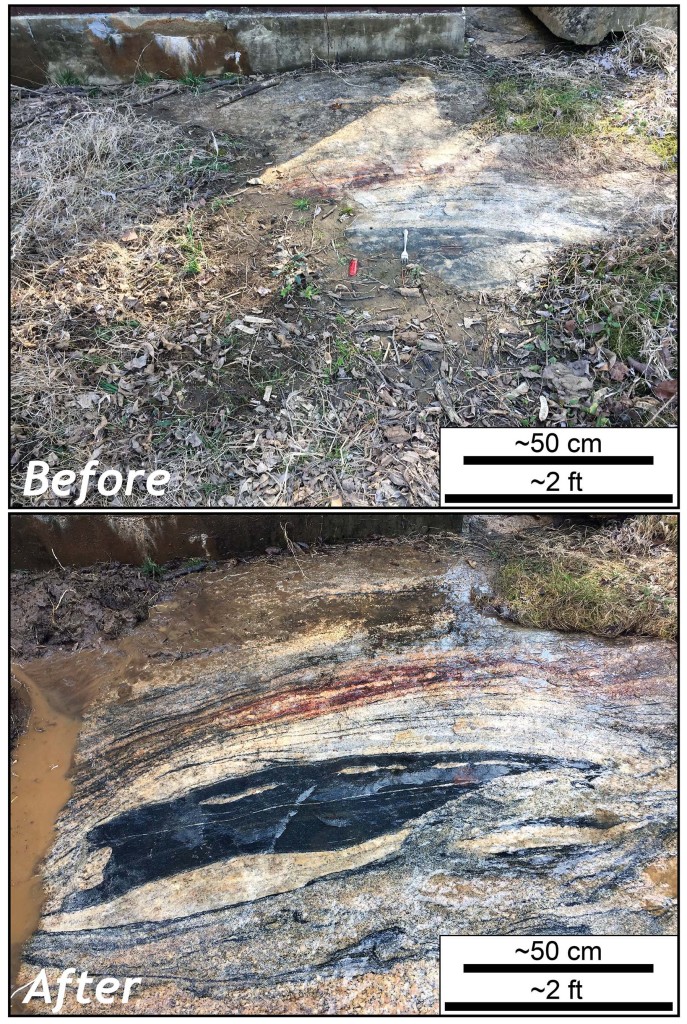

In some locations, well-exposed only a decade ago, the rock was barely visible. Check out the ‘before’ image below – yuck! Not much bedrock to see, although there was urban detritus (look for a fork and a lighter). After 15 minutes of power-washing something wonderful re-emerged. The dark rock is a biotite-hornblende schist, and forms a boudin that’s surrounded by both coarse-grained granite and banded granite. The schist is older than the granite; as the granite intruded and flowed, the schist was stretched and boudinaged. But look carefully at the dark schist; it contains a whitish feldspar-rich layer that also forms boudins. Boudins inside of a boudin! And no boudin aficionado could fail to appreciate the different shapes at either end of the big boudin. This is the stuff of a structural geologist’s wildest and most wonderful of dreams.

In total, we power-washed between 40 and 50 m2 at three locations. But we could have power-washed for days and not cleaned off the vast expanse of outcrop. Progress was made, but it’ll be interesting to see how our effort holds up in this dynamic environment. The exposures south of Belle Isle are a popular spot, especially on a warm mid-February Sunday, so there were lots of people out-and-about, most curious about why anyone would power-wash rocks.

Pavement exposure with well-exposed xenoliths in banded granite south of Belle Isle. Photo from March 2008, William & Mary geologists Denton Willis and Ali Snell for scale.

This spring, Brent Owens and I are leading a field trip after the Geological Society of America’s Southeastern section meeting in Richmond to examine granitic rocks of the Petersburg pluton (or more properly: a batholith). The purpose of the trip is to examine outcrops and quarries that expose the Petersburg Granite and tell the story of the magma’s genesis, emplacement, and later deformation. We’ll be taking participants to see the fruits of our power-washing endeavors at Belle Isle. Interested in joining us? For more information check out the field trip website.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.

From the posting title, I thought I was going to click and learn about some recent flooding event that exposed a bunch of covered outcrops…I chuckled when I learned that you meant literal power washing.

Sidenote: do you have to register for the meeting to attend a field trip?