Nine Down, Seven Across for Planetary Geology

Meara Carlin ’23

There is an interesting grey area when dealing with planetary geology. The first thing someone usually thinks of when geology is mentioned is rocks. However, in the case of planetary geology a lot of times (not all), rock samples are not part of the science. So, what is geology without rocks? It’s a crossword puzzle. Unlike many other forms of puzzles, crosswords provide small clues and once you fill in one word it helps solve the others until eventually the entire puzzle is complete. My journey into planetary research, under the guidance of Dr. Alyssa Rhoden and Dr. Jon Kay, was not a slow walk into the shallow end of the pool, but more like a head first dive into the ocean. I had no experience with anything planetary or even how to start learning about it. All I knew is that I loved geology and I loved space, so I decided I’d throw myself into it and see where I ended up. One of the most prominent thoughts I remember having was my research is a puzzle to solve and once I started filling in those words everything started to fall into place.

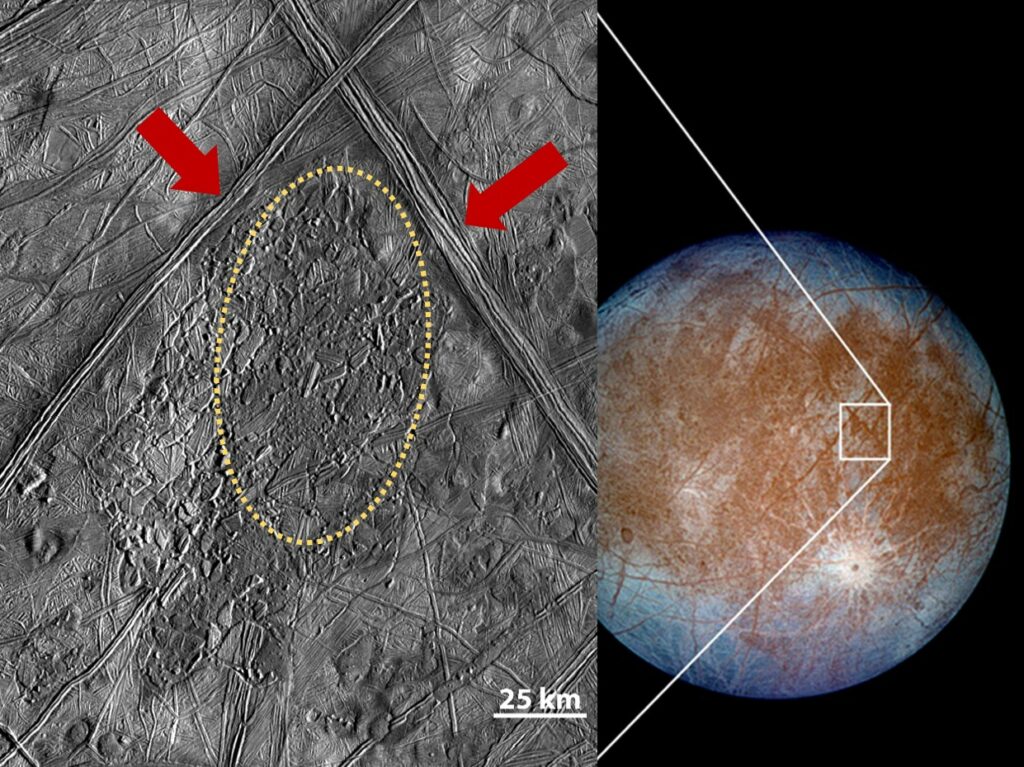

Figure 1 (above) are images of Europa’s surface taken by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft in 1996 and 1997 (NASA/JPL/DLR). Image on the left shows an area of Europa called Conamara Chaos. It displays non-ice material that formed from geological activity (dashed circle) and the red arrows point to ridges and fractures in the ice shell (Cox et al., 2008).

My research is focused on Europa, the sixth closest moon to Jupiter. It is a tad smaller in size than our own moon at 3,000 km (1,900 miles) in diameter. Its outer layer is a large ice shell with a body of water underneath and a solid rock center. Europa is a curious moon with many ‘what ifs’ and not many concrete answers as to its processes and internal structure. My goal is to understand the relationship between surface features/microfeatures (different types that are less than or equal to 100 km2 in area) and any tectonic plate motion. Understanding the relationship, or lack thereof, between them can give further insight into the processes that have affected Europa.

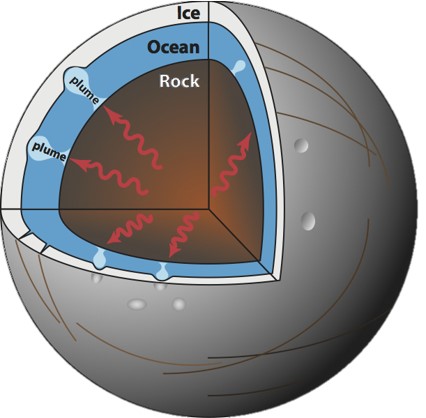

Figure 2 (above) Cross section of Europa showcasing the ice shell, liquid ocean, and rock core. The plumes are theorized to cause some of the surface features. There is still speculation as to the chemical composition of the ocean (Life beyond earth, 2019).

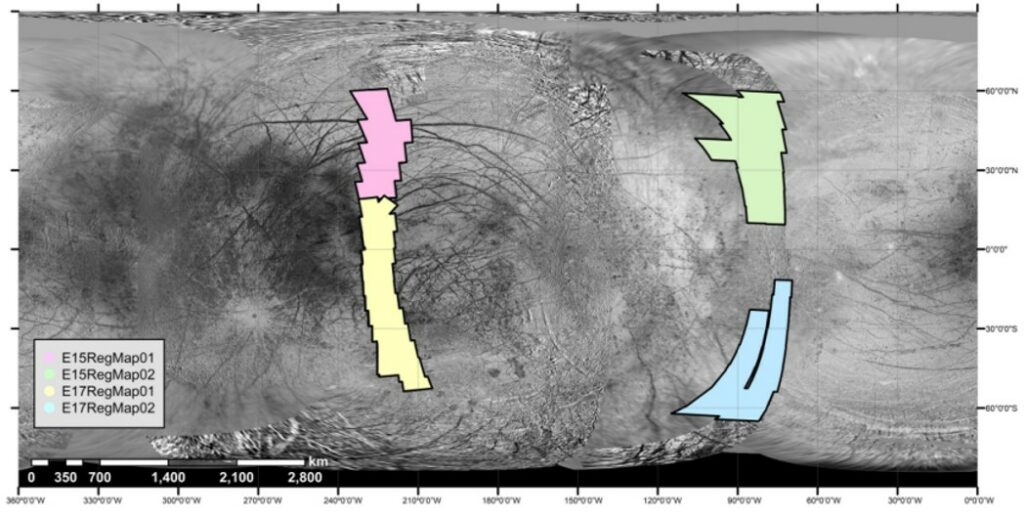

So how do we study a moon without any samples? I use images that are stitched together to create a high-resolution mosaic. These are called RegMaps. This is the point where my research got tricky. In order to map and analyze these four Europa RegMaps, I used ArcGIS Pro: a geographic mapping information system. ArcGIS Pro would help me visualize the surface features and later calculate their orientation.

Figure 3 (above) USGS (2002) basemap with four color coded overlays that represent the RegMaps. Pink: E15RegMap01 (top left), Green: E15RegMap02 (top right), Yellow: E17RegMap01 (bottom left), Blue: E17RegMap02 (bottom right). This image is a part of Mapping Europa’s microfeatures in regional mosaics: New constraints on formation models published in volume 329 of Icarus. It was written by a former William & Mary student, Jessica Noviella, in 2019.

Learning ArcGIS Pro was a feat. For four weeks last summer, I learned how to use the program alongside doing my research. I would recommend learning Arc first before attempting research, but on the bright side I learned a valuable tool and Google became my best friend. So, all the tears from accidentally deleting my work, not once, but three separate times was all worth it in the end. During those four weeks, my first task was to line up the four RegMaps on top of a basemap of Europa. This proved to be more difficult than just making sure everything was projected into the same coordinate system. Since that didn’t work, I had to manually place control points around all the RegMaps to shift them into place over the basemap. After fiddling for a few days with the alignment of the maps, I finally started on the surface feature analysis of the Bright Plains area of Europa.

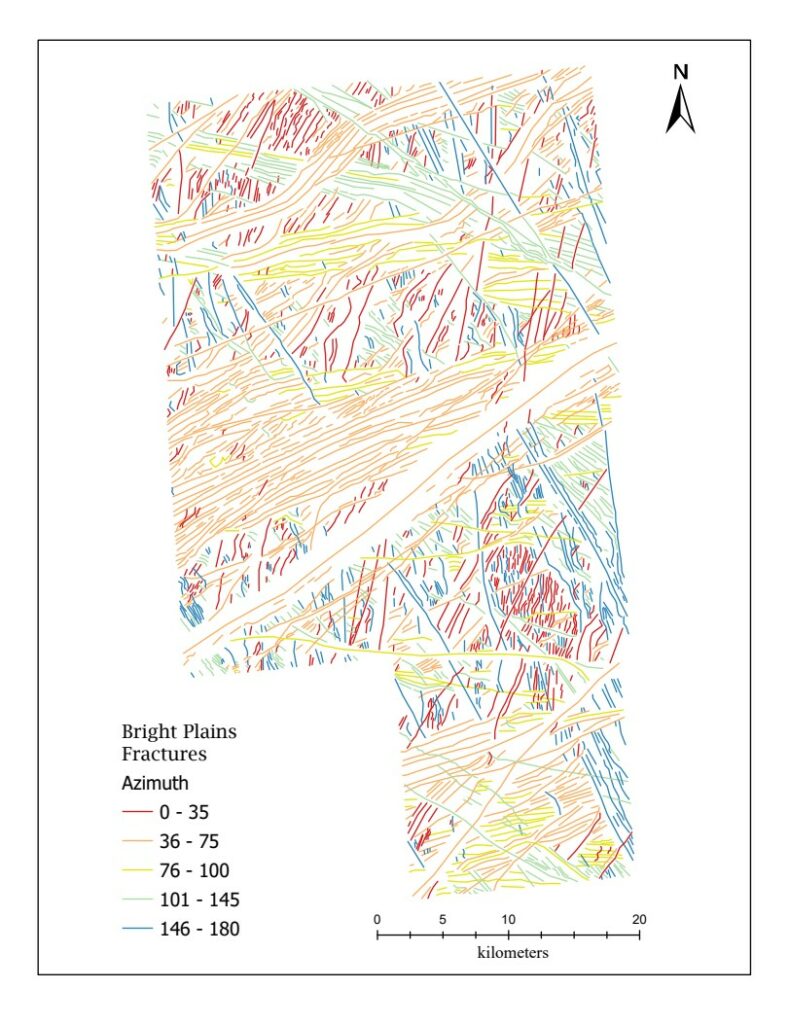

The Bright Plains area of Europa is a small portion of the surface that is riddled with surface features like ridge complexes and flexure fractures. Mapping this very small area of Europa probably took the longest to complete out of anything I’ve done so far. To give a little perspective, the four RegMaps only cover about 6% of Europa’s surface. The Bright Plains region is like a spec compared to the four maps and it still took me about a week and a half to map all the surface features.

Figure 4 (above) is the Bright Plains region map. All surface features are marked and color coded based on their directional orientation (azimuth). Further mapping was done to separate out the flexure fractures and the ridges. All the orientations were originally calculated from 0-360, but were converted to 0-180.

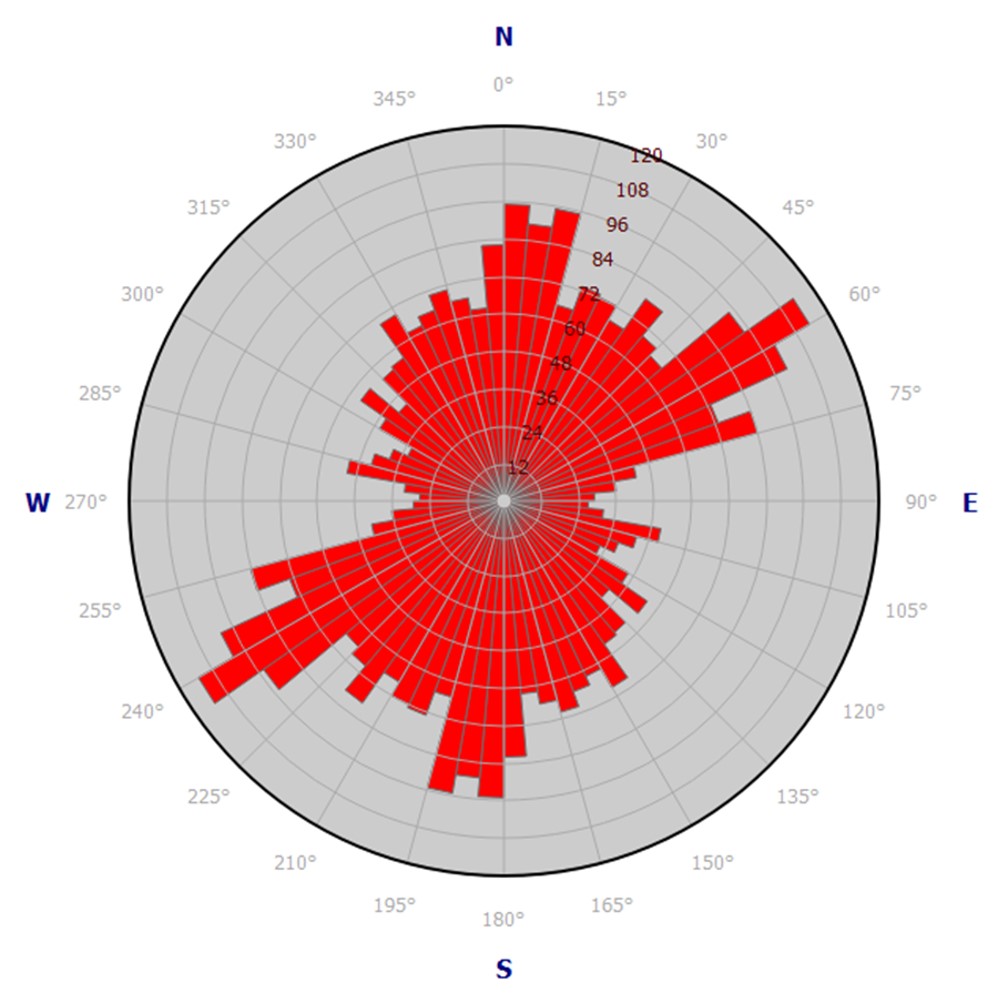

I ended up mapping over 2,000 features which I then categorized into five classes based on their orientation (azimuth). Having all this data, I was able to calculate averages, minimums, maximums, ranges, and counts. The plot below is a rose diagram with all the 2,000+ azimuths to better visualize the data.

Rose Diagram showing the distribution of directional data collected from the mapping of the Bright Plains region. 2,000+ orientations are displayed here.

Finishing all this work at the end of the four weeks felt like it left me at a standstill. Even though I had done this research that I was proud of, what did it all mean? Why did I do it? The best way I can explain it is I have completed the down words in my crossword puzzle, but I have yet to complete the across words. I have data and information, but I am missing the next part of that equation, which is the rigid plate motion. That will be the next step in my research. I will map strike-slip faults, which can be indicators of plate motion, and then see if there is any relationship between the microfeatures and the faults. Overall, this process, that has just begun, has taught me not just about research and geology, but about myself and my work ethic. As a perfectionist it is always difficult for me to start anything because in the back of my head, I know it will never be perfect. But this process has showcased to me whether you start a crossword by the across words, the downs, or a mix of both, just starting is the most important part.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.

Meara- I loved reading through this. I especially like the rose diagram yo created; it definitely helps visualize the data you have collected. I’m so impressed by your work and tenacity. Excited to hear more once you get the “across words” filled in.

Hi Meara – very cool stuff here. Did you have to create a custom projection for Europa in Arc or was that pre-existing? I enjoyed your write up and hope your research continues to go well. Nice job!

Hi Ryan,

Thank you for taking the time to read my blog. I really appreciate it. Finding a projected coordinate system took some research and some trial and error. I ended up on a projection called Plate Carrée, which was already pre-existing. It’s a pretty simple projection, but it seemed to work and keep everything consistent.