A Frenzy of Fall Field Trips 1: The Rockfish River Watershed

Note: this is the first installment in what will be a frenzy of posts about recent fall field trips in the William & Mary Geology department.

This semester, one of the courses I’m teaching is Geology 311- Field Methods in the Earth Sciences. As the name implies we venture to the field to collect our primary data. The overarching goal of the course is to enable students to acquire the skills needed for successful, field-based earth and environmental science research. Our projects are not canned exercises; rather they are research projects that generate new information. It’s not unusual for these class projects to morph into senior thesis projects for some students, and ultimately lead to scientific publication.

Last Friday we set out for the Rockfish Valley and the Blue Ridge Mountains. One of our semester projects is to study the geology of the Rockfish River watershed. We’ve partnered with the Rockfish Valley Foundation, a community group working to preserve the natural, historical, ecological, and agricultural resources of the Rockfish Valley. We’ll produce a series of maps, cross sections, and educational content focused on the geology, environment, and hydrology of this scenic Virginia region.

The 2019 William & Mary Field Methods class strikes a pose on a soapstone outcrop in Schuyler, Virginia.

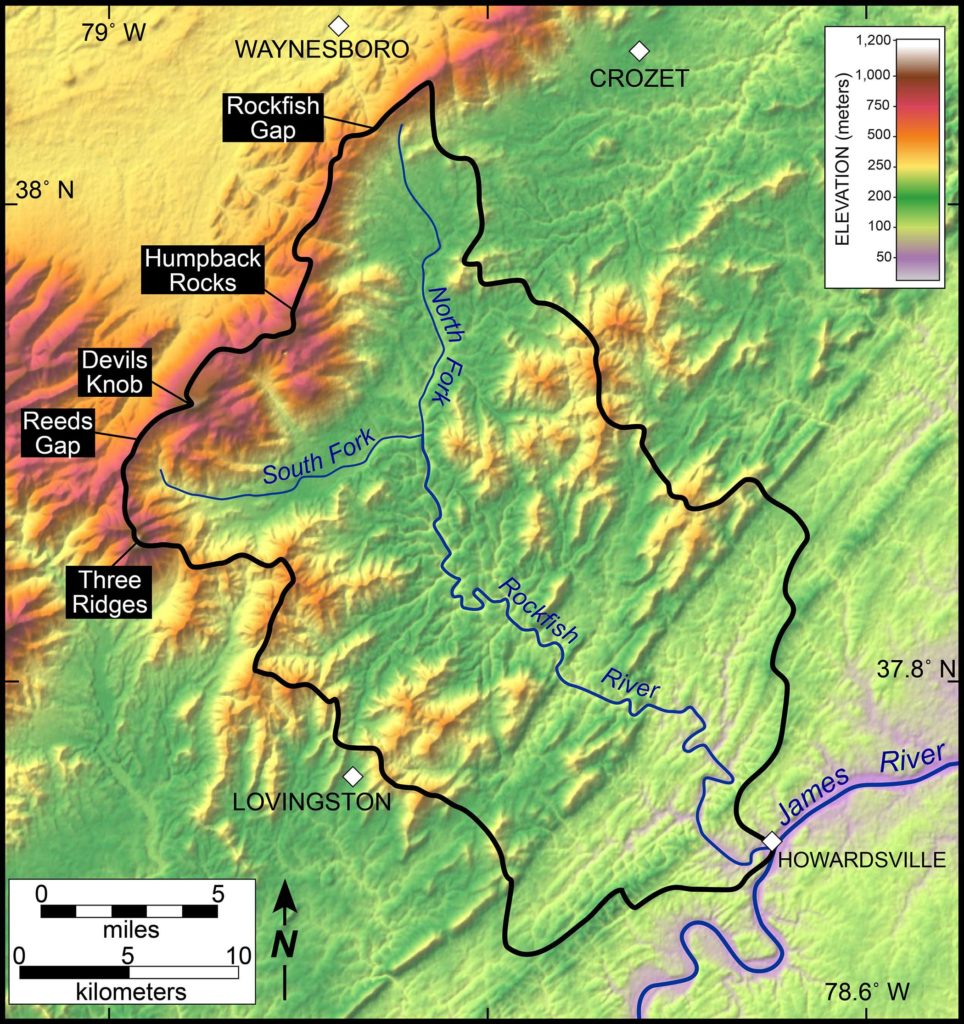

The Rockfish River is a ~50 km long tributary of the James River, whose headwater streams cascade off the crest of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The basin’s highpoint is the summit of Three Ridges (~1,210 m), and its low point occurs where the Rockfish reaches the James River at Howardsville (~90 m). Rockfish Gap, at the northern edge of the basin, has long been an important transportation route across the Blue Ridge. The Rockfish Valley lies at the southeastern foot of the Blue Ridge and is transected by the North and South Forks of the Rockfish River. Starting in the 1970s, with the opening of the Wintergreen Resort on Devils Knob, and continuing with further development in the Rockfish Valley this part of Nelson County has acquired a distinctive ambience. During the past decade, the Rockfish Valley and Virginia Rt. 151 have become a prominent tourist destination as breweries, cideries, wineries, and distilleries have sprung forth.

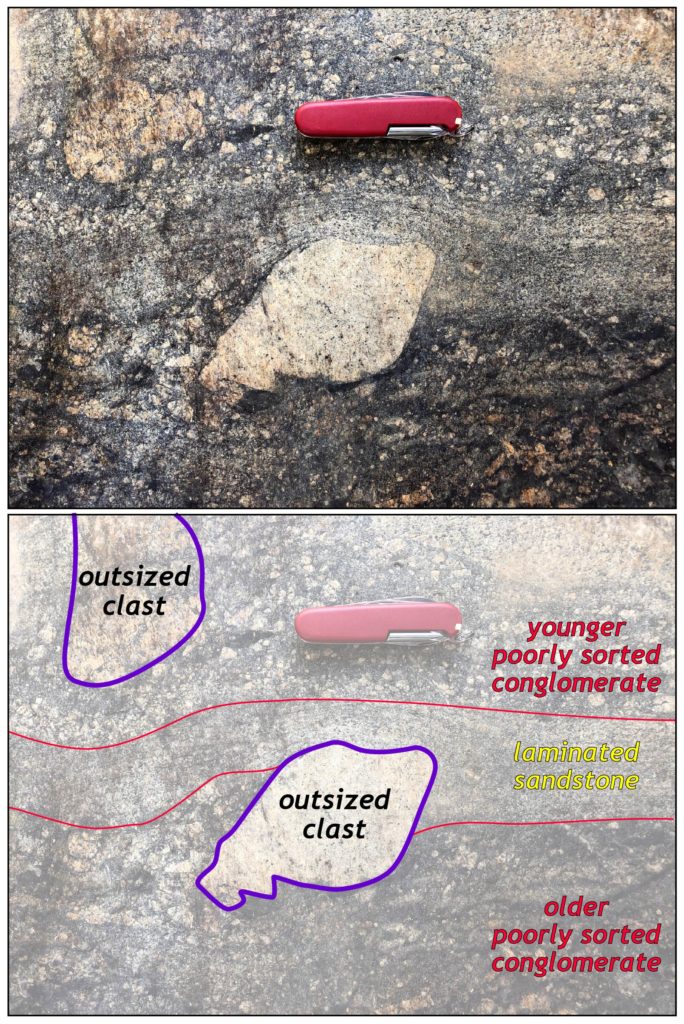

The Rockfish River traverses the Blue Ridge geological province. From 550-million-year-old greenstone exposed along the Blue Ridge Parkway and at Humpback Rocks to some of Virginia’s oldest rocks (1.2 billion-year-old) gneiss in the foothills, there is a wealth of bedrock geology. The geology in the Rockfish watershed is so iconic that a number of geological features and rock units have been named here including the Rockfish Conglomerate (named in the 1930s), the Rockfish Valley fault zone (named in the 1970s), and the Rockfish River pluton (named in the 1980s). With all these names, it can be confusing. Part of our goal is to tell the story of the region’s geological heritage in a compelling, but digestible, fashion.

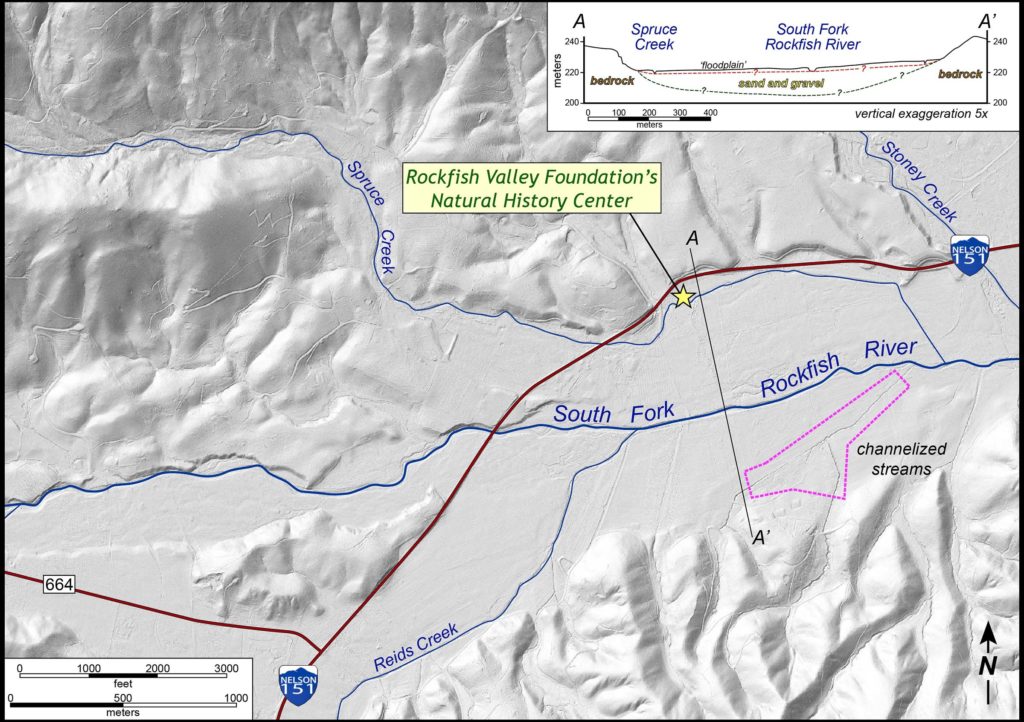

On Saturday morning, we wandered onto the broad floodplain of the Rockfish River’s South Fork. Here, the river is small, but the floodplain is wide. We pondered what controls the width of a river’s floodplain. Some authors have speculated that the Rockfish River may be an underfit stream, whose valley is too large for the discharge of the modern river, and that the valley morphology is a vestige from another time when flows were larger. Later this semester we’ll return to complete a Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) survey and determine the thickness and geometry of the alluvial sediments in the Rockfish Valley.

Using LiDAR data, we can make topographic and shaded relief maps at fabulously detailed scales. These maps enable us to see many natural and anthropogenic features on the landscape (checkout the map below).

Shaded relief map of the South Fork of the Rockfish. Click to enlarge the map. Note the channelized streams along the South Fork’s floodplain. We aim to determine the thickness and character of the alluvial deposits later this semester (see the cross section).

The Rockfish floodplain has long been utilized for agriculture. The Rockfish Valley was settled in the middle of the 18th century, and much land use change has happened over the past +250 years. It’s clear from the LiDAR imagery that many of the Rockfish Valley’s streams have been channelized — with stream courses straightened out and turned into little more than drainage ditches. This process started as the early farmers worked to make arable land in the Rockfish Valley, and continued throughout the 20th century.

On the night of August 19-20, 1969, a great catastrophe occurred in Nelson County as the remnants of Hurricane Camille generated 40 to 95 cm (15 to 37”) of rainfall in a matter of hours. Steep hillslopes failed, thousands of debris flows coursed out of mountain hollows, and streams like the Rockfish flooded at a scale never witnessed before. More than 150 people died in Nelson County that day, and scores of public bridges and highways were washed away. The riparian areas along the Rockfish River were throttled beyond belief. Although it has been fifty years since that storm, there are still signs of Camille’s wrath, including the debris slide scars visible on many hillsides. This year’s Virginia Geological Field Conference will focus on the impacts of Camille on Nelson County. After Camille, government engineers straightened and channelized much of the Rockfish River in an attempt to mitigate future floods.

A post Camille image from the Rockfish River at the Rockfish Conglomerate’s type location. Note only the bridge pilings remain after the Camille flood. From No. 69-2339, Virginia Governor’s Negative Collection, Library of Virginia.

During the past two decades, the engineering of straightened and channelized streams for flood control has lost favor. Stream restoration is now in vogue. Restoration involves landscape engineering, but with the goal of improving the environmental health of stream systems by stabilizing channels, reducing erosion, and creating a ‘more natural’ riparian system. Typically, streams are restored to produce the classic meandering channel geometry, viewed by many as both a beautiful and natural form that rivers inherently possess. Some of the previously channelized parts of the Rockfish’s South Fork, have undergone stream restoration projects in recent years.

Along those reaches of the river, large blocks of rock (transported by trucks more than 100 kilometers from where they were quarried!) have been placed by heavy equipment to armor stream banks and create a succession of riffles/pools in the river. It’s a curious site in a stream whose natural sediment consists primarily of cobbles and coarse sand.

What was the geometry and character of the Rockfish River system prior to settlement and land use changes brought on by agriculture? Was the South Fork a meandering stream or a complex braided and anastomosing channel network that transported coarse debris from the Blue Ridge Mountains? What are the environmental consequences of stream restoration, especially when a non-natural river morphology is forced on the system?

For better-or-worse, stream restoration seems here to stay, since government agencies keep funding restoration projects even as geomorphologists caution about its overuse and overstated efficacy. As our Rockfish research project continues, we’ll discuss the pros and cons of stream restoration in this setting.

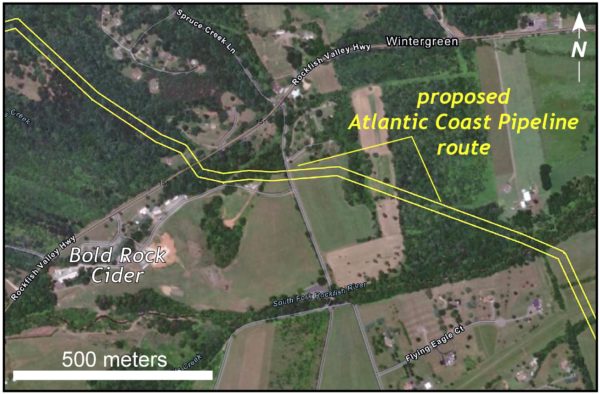

Proposed route of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline across the Rockfish Valley. Map from the Atlantic Coast Pipeline website.

However, a bigger environmental issue looming over the Rockfish Valley concerns the construction of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, a natural gas pipeline intended to transport gas from the Appalachian Basin in West Virginia to the Atlantic Coast. The proposed pipeline route tunnels beneath the Blue Ridge Parkway at Reeds Gap and descends steeply along a set of ridges to the Rockfish Valley. Significant questions still remain about the viability of this route that will involve mountaintop removal in the Blue Ridge and the shallow burial of the pipeline beneath the Rockfish River and its broad floodplain.

The Geology 311 class’ field research will provide information about the subsurface geometry in the Rockfish Valley, it’s another example where basic research can inform policy and should counsel both environmental practice and hazard mitigation.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.

My in-laws live in Stoney Creek, and we’ll be there for 2.5 weeks over the holidays. I have always loved the landscape there, and now we particularly enjoy the RVF’s kids trail/mud kitchen/playground. I’ll be interested to see the results of the GPR study- the underfit stream idea is an interesting one.

Chuck,

I’ve been dying to get a topo map of the Rockfish River Watershed with all or main streams labelled. I’ve asked USGS, Lindsey Hill of Nelson High School, even Dick Whitehead of Wiley Wilson. If you guys create a map, could I get a copy. Nature Foundation will pay.

Thanks,

Kathie