Dispatches from Oman: Juxtaposition

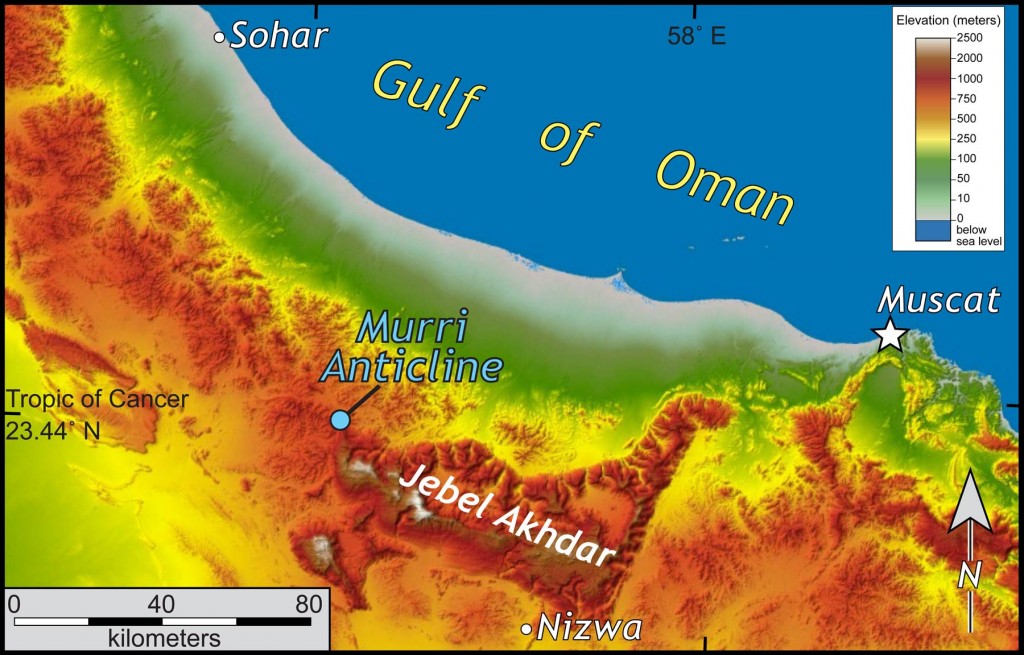

A new semester awaits 11,000 kilometers away in Williamsburg. Time to depart Oman, but before heading west towards home there was one last mountain to climb. I’ve had my eye on this ridge at the north end of Jebel Akhdar for months, as the view from its crest should provide an exceptional overview of the region’s geology.

The ridge stands ~800 m (~2600 ft.) above the small villages of Murri and Ash Shakdar. We parked the saloon car in the morning shadows and set off—I headed for the ridge, and Alex bore on to the wadi that cuts dramatically through the ridge. This is an anticlinal ridge and the wadi slices neatly across the anticline providing a spectacular cross section through folded strata.

I walked up the eastern dip slope of this geologic structure to the gently dipping strata along the ridgecrest; below Alex negotiated house-sized boulders in the wadi bottom.

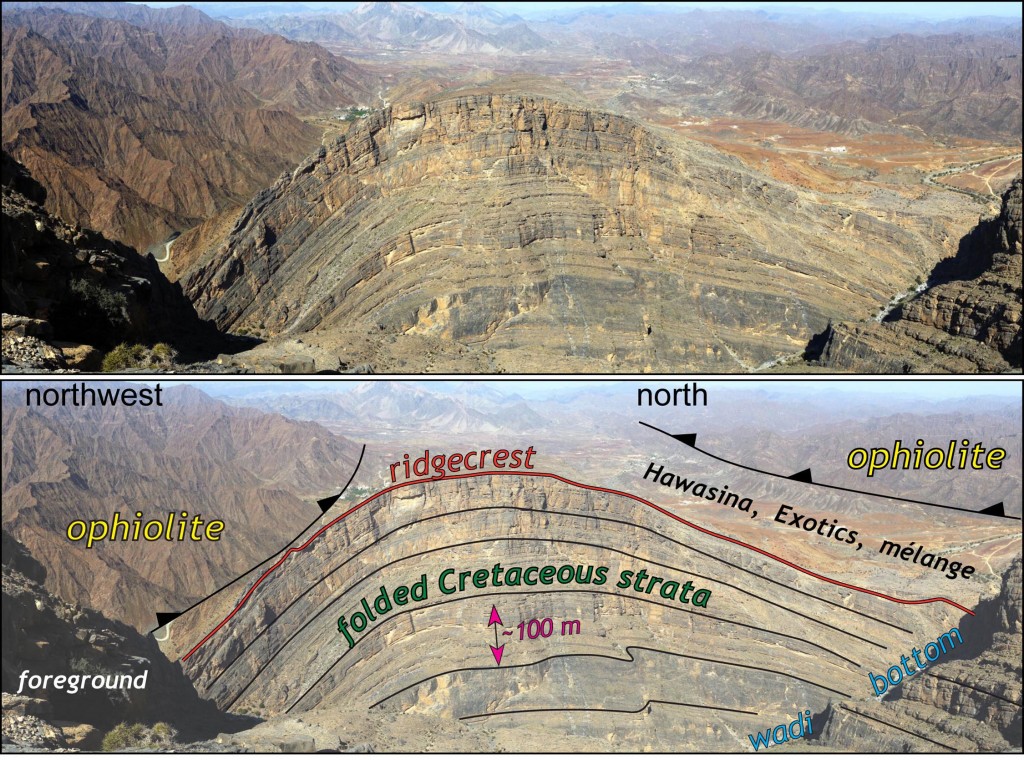

View from the top of the Murri anticline, northern Oman (view to north-northwest). Annotated geology in lower image, note the ophiolite on either side of the Cretaceous strata. The wadi bottom is ~700 m below. This image will be posted as a Gigapan in the coming weeks.

Rocks exposed along the ridge and in the gorge below are Cretaceous limestones deposited some 95 to 115 million years ago in reefs and shallow warm seas on the northeastern margin of Arabia. These are the strata that underlie much of the alpine scenery in northern Oman. Although these strata are folded in dramatic fashion, the rocks are essentially in the same location as where they were originally deposited. This sequence of rocks is considered autochthonous, a tough-to-spell geologic term for rocks that are still located where the formed. In contrast, allochthonous rocks are no longer where they originally formed, rather, they’ve been displaced along faults and, in many cases, are far traveled bits of wayward crust.

Look to the periphery of this photo and you’ll notice ragged brown terrain, both to the northeast and northwest of the anticlinal ridge. This is the ophiolite underlain by peridotite, a dense dark rock that originally formed in the mantle 15 to 20 kilometers (9 to 12 mi.) below the ocean floor. In some locations there are other allochthonous rocks including a complex sequence of deep-sea sedimentary rocks (known as the Hawasina sequence), exotic blocks of limestone, and mélange (which, just as the name implies is a tectonic swirly pie of many rocks) between the ophiolite and the limestones. The contact between these geologic units is a thrust fault of the first order.

While standing on the ridge taking in the scene one word came to mind—juxtaposition. I’ll use the word in a sentence:

The juxtaposition of rocks from the Earth’s mantle (highly allochthonous rocks) against the shallow marine rocks (autochthonous strata) is a profound geologic sight.

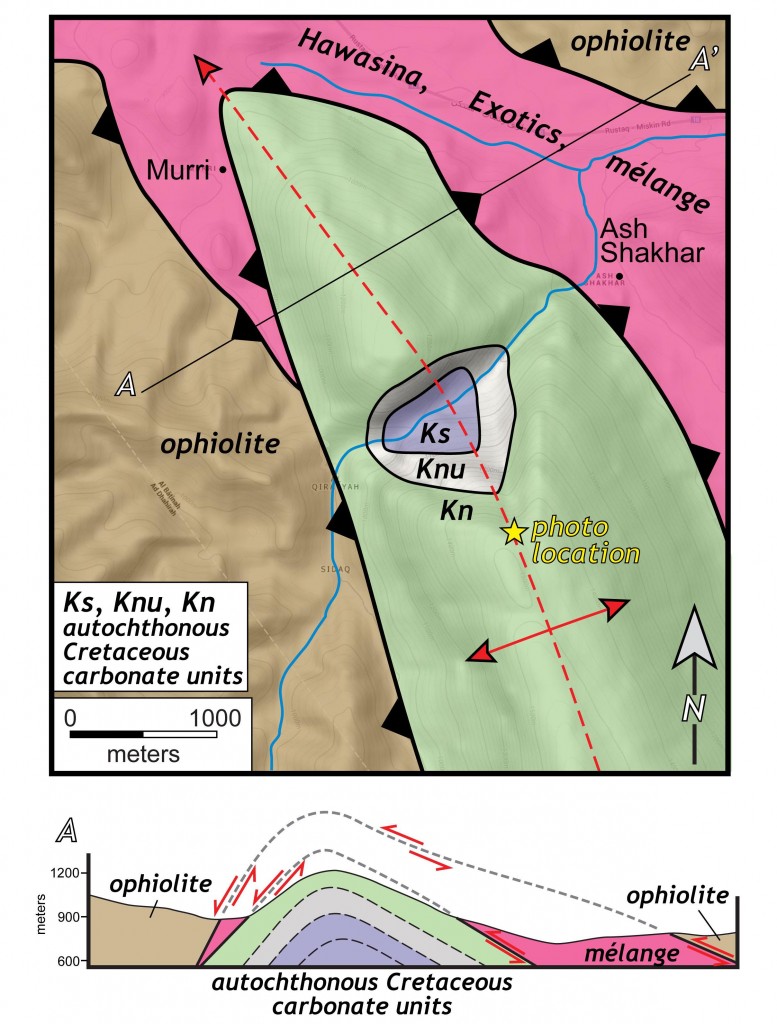

Geologic map and cross section of the Murri anticline and Oman ophiolite. Ophiolite is juxtaposed against mélange and autochthonous limestones.

The arched nature of the sequence makes it easy to visualize that the ophiolite was thrust long distances up and over the Cretaceous limestone. Prior to erosion of the modern mountain range (the terrain we see today) the juxtaposed ophiolite from the Deep Earth would have overlain the autochthonous rocks. Later deformed folded the rocks and then erosive surface processes removed the ophiolite sequence to expose the autochthonous strata below. That is quite a story!

There are other compelling geologic stories to share about Oman. In the coming weeks I’ll post more pieces on Oman’s geology and upload our Gigapans. Alex and I are also working up a series of videos that illustrate both our travels through Oman and the geology of this wonderful country. Music Professor Anne Rasmussen and I are moving forward with plans to take a field course/study abroad program to Oman in the future. Much to do back in Williamsburg.

No comments.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.