The Schuyler Sisters Field Adventures: A Top 10 List

You’ve heard of David Letterman’s Top 10 lists, or actually maybe you Gen Zers haven’t, but we’re sure you can pick up on the idea.

Last time we checked in our summer of research had just begun. More than a month later we are way more seasoned, our feet more calloused, and our shelf in the Rock Room filled with more rocks. We’re also further down the path towards having a living, breathing geologic map. Well, that personification may not be entirely truthful, but the living and breathing part checks out according to our TikTok account.

Many strange and exciting things have happened to us while doing field work, and we wanted to tie it all together so that you (our dedicated fanbase) could live vicariously through some of our best moments yet. So, without further ado, we give you the Schuyler Sisters’ list of our most epic summer field adventures.

1. A Whale of an Outcrop

The first outcrop we examined in the Schuyler area is a large whaleback outcrop with a roughly convex shape. The outcrop exposes a distinctive biotite-bearing granitoid gneiss, which has been referred to as an augen (German for ‘eye’) gneiss in the geologic literature. Biotite-bearing granitoid gneiss is a mouthful, so to keep it short while discussing this rock, we refer to it as Ybg- ‘Y’ is the standard unit abbreviation for the Mesoproterozoic, the age of the rock and ‘bg’ for biotite-bearing gneiss. This geologic unit is part of the Virginia basement complex that formed over 1 billion years ago. These are ancient rocks! In fact, they are the oldest rocks in the Schuyler area and form the ‘basement’ upon which the younger cover rocks were deposited on. Since then, we’ve examined hundreds of outcrops – some are memorable for their geological significance or intrinsically cool while others are poorly-exposed weathered bits of the Earth’s crust, but serve as data nonetheless.

2. Bodacious Black Bears

On a traverse in late June, we were descending a clear-cut slope, when two bodacious black bears appeared on the opposite side of the valley. They seemed to be on a traverse of their own. Feeling secure with our distance from the bears, we enjoyed the scene as they galloped off into the distant woods. Ironically, the bears weren’t the only surprise of the traverse. For much of the day we’d been finding outcrops of Lynchburg Group meta-sandstones, but here we came across an outcrop of an unexpected ultramafic rock. That’s all part of the geological mapping process – making new and unexpected discoveries.

A lucky clip of the galloping bear.

3. Geo Quest at Quarry Gardens

The Quarry Gardens is a special place and it’s in our study area. The property, owned by Armand and Bernice Thieblot, includes several old soapstone quarries, native plant galleries, walking trails, and a visitor center with exhibits on the history of soapstone quarrying as well as the local flora and fauna. The Gardens have a perfect tagline – “a landscape carved by industry and renewed by nature”. The Thieblot’s have kindly granted us access to research the geology. We’ve spent a few days on their trails and also scrambled over the steep slopes near the Rockfish River. In addition to soapstone, we’ve recognized that a major contact between units in the Lynchburg Group is exposed here. We’re providing Quarry Gardens with a detailed map and a 3D model of the geology underfoot at this distinctive site.

4. Plying the Rockfish River by Paddle

On the last day of June, we embarked on an epic geological traverse that involved paddling the Rockfish River. We set out in three canoes with lots of sunscreen and our trusty dry bags. The goal was to study the exposed bedrock outcrops in the river, so to the amazement of our canoe outfitters, we were rather pleased that the river’s discharge was well below normal. Each vessel coined a name, and a style of its own. The Voyager prided themselves on navigating every rapid in the most challenging (stupid) way they could, even attempting one backwards. The Double Zach took a more refined approach, possibly acquiring less water in their boat, and a more peaceful journey. And finally, there was the Old Reliable – that seemed to always be at the front of the pack, leading the way to more and more and more outcrops.

The Voyager and Double Zach in action (or rather inaction).

5. Bunky’s Baby Debunked

A long time ago, in a galaxy far far away, or rather it was 1985, in Blacksburg, Virginia, when Frederick ‘Bunky’ Wehr published a paper describing the stratigraphy of the Lynchburg Group, a meta-sedimentary sequence in central Virginia. Wehr noted the occurrence of a felsic volcanic rock within the uppermost unit in the Lynchburg Group. More than 35 years later the Schuyler Sisters were called in to investigate this strange occurrence at a scrappy little roadcut. The light color and fine-grained nature of the rocks at the outcrop seemed initially promising, however closer inspection revealed the sample’s true nature. X-Ray fluorescence (XRF) data indicates the rock contains ~85% SiO2, which is more typical of a quartzite than a felsic volcanic rock. We’d hoped it’d be a felsic volcanic because minerals in that rock can be isotopically dated thereby providing a numeric age for the deposition of the Lynchburg Group (which is poorly constrained).

Don’t blink or you’ll miss it – Bunky’s Baby via car window.

6. Maxing and Relaxing at Base Camp(s)

Some of our fondest field memories come from our various base camps. After a long day of traversing thru the sticky heat, there is nothing better than relaxing in our camp chairs, munching on chips and salsa all while enjoying a well-deserved cold beverage. On really hot days, we cool off with a swim in the James, or the Rockfish, or the Tye rivers. Despite our moderately primitive camp conditions, dinner and the occasional cooking lesson are never short of exceptional. The camp menu thus far has included burritos, turkey burgers, pasta, curry, and even cheesy eggs! The occasional post-dinner wiffle ball and soccer matches provide additional excitement.

7. Going Full Nelson with the Rockfish Valley Foundation

We’re working with the Rockfish Valley Foundation (RVF) to create educational content that links the underlying geology to the landscape and environment. We’re updating field guides to the RVF’s trail system and the Nelson County Scenic Loop with new maps and digital content. Last week we enjoyed a cookout with RVF board members to discuss our plans. The food was great, and the company was even better. It was refreshing to talk with a group of people far more experienced in the trials of life than us, but just as eager to learn and dedicate themselves to the exploration of science and preserving our environment.

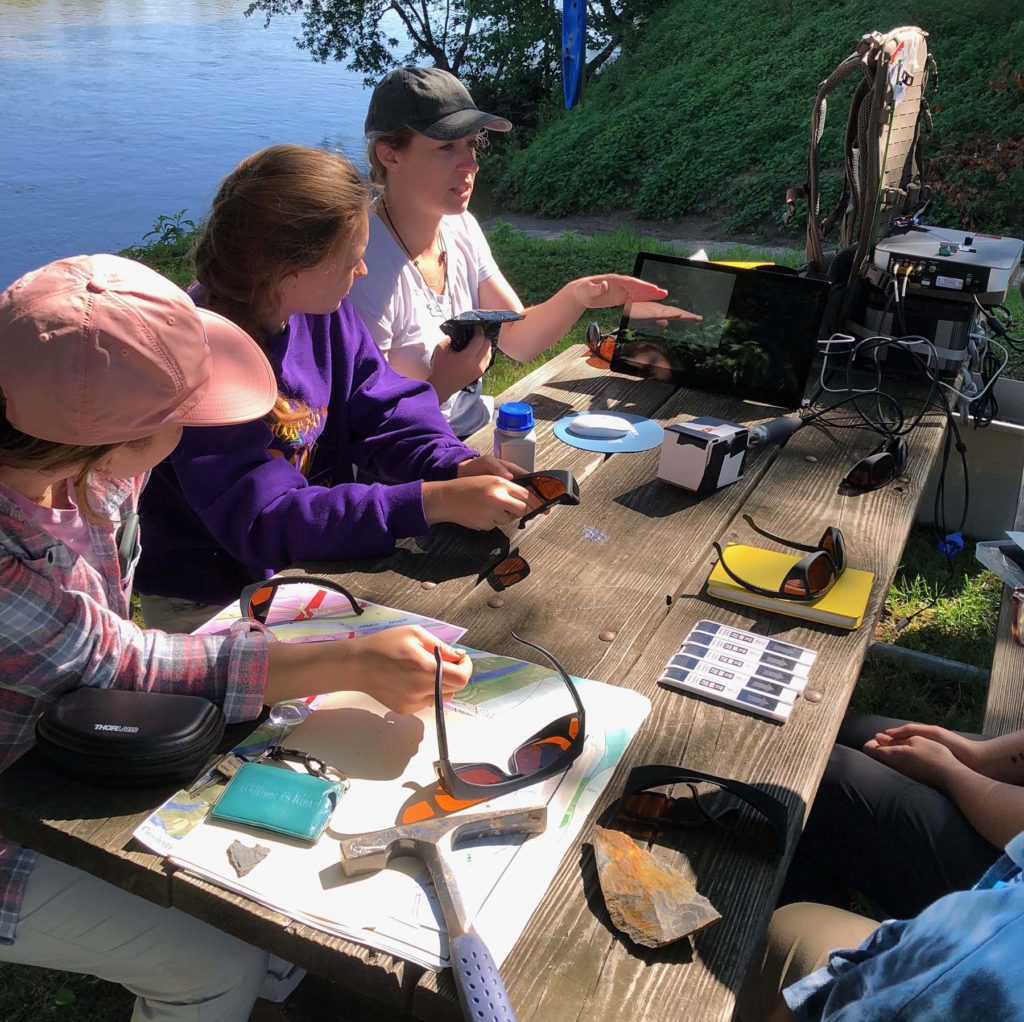

8. Collaborative Science with the U.S. Geological Survey

We’ve teamed up with Dr. Rebecca Stokes and Dr. Aaron Judd from the U.S. Geological Survey to use Raman spectroscopy as a tool for analyzing graphite in these metamorphic rocks. Graphite – it’s a mineral composed of just carbon and was once organic matter deposited in the ancient sediment that would become the rocks of the Lynchburg Group. These same rocks were heated up and metamorphosed during the great tectonic conflagration that created the structure of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Raman spectroscopy enables us to estimate the peak metamorphic temperatures that rocks in the Schuyler area enjoyed. This Fall, we’ll be presenting the results of this research at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America. All told we’ve got four research presentations lined up for the Fall. As the Schuyler Sisters from Hamilton sing – “There’s a million things we haven’t done, just you wait.” We’re working through our list!

9. Taking It to New Highs and Lows

One goal of our summer exploration was to reach the highest and lowest points in our study area. Appleberry Mountain tops out at 560 meters above sea level (1,837’), and we summited the bramble-armored peak on a steamy afternoon traverse. On Appleberry Mountain’s southern ridge, the basement-cover contact (aka- the Great Unconformity) is exposed – it’s a profound geological boundary. The lowest point in the Schuyler area is 96 meters above sea level (315’) and occurs along the Rockfish River at the southern edge of our study area. We floated over this point while paddling down the Rockfish River (see #4). Along this stretch of river, the outcrops tell the story of a changing world as the newly borne Iapetus Ocean stretched its watery footprint way across ancient North America.

Left- On Appleberry Mountain. Right- The Voyager after descending a Rockfish River rapid near the study area’s lowest point.

10. Logging Rock Core at the Old Mill Building in Schuyler

One of our favorite activities is logging rock core at the old mill building in Schuyler – capital of the American soapstone industry. Earlier this year, Polycor commenced an exploratory drilling program at some of the old quarry sites in the Schuyler area. We’re studying the core to advise Polycor Inc. on their soapstone resources. The scientific value of the core is HUGE as it affords a continuous record of how these rare rock bodies change from top to bottom. We want to understand how and when these Mg-rich and Si-poor rocks formed. Core logging involves lifting 4’ long core boxes, each with 20’ of drill core inside, onto a table-top for a detailed inspection which includes systematically describing the core, using a handheld XRF probe to analyze the bulk chemistry and a Schmidt Hammer to estimate the hardness and rock strength. Core logging is slow going, but sometimes that is the nature of science research.

Top: Our band of Sisters with rock core at Schuyler. Bottom left: rock core in boxes, boxes are 4’ long and contain ~20’ per box. Bottom right: complex mineral vein in soapstone.

Honorable mention – Chair Destroying Champion

On one particularly memorable evening at base camp, we were gathered around a picnic table while Professor Chuck Bailey sat firmly rooted in a camp chair (as older folks need the back support). Suddenly, the night air was punctuated with a horrible ripping sound and we all turned to see that Chuck had fallen straight through his chair. As if that wasn’t enough ammunition to torture Chuck for the rest of summer, it happened AGAIN a few weeks later in an almost identical chair. The Chunky Monkey strikes again.

No comments.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.