Summer in Maasailand: Immunization Record Digitization & Making Friends in Rural Kenya

By Katie O’Neill ’24

The Global Research Institute’s Summer Fellows Program provides international experiential learning opportunities to W&M students. This post is one installment of a series highlighting the 2023 Fellows’ key discoveries and formative experiences.

I spent my time this summer working with Community Health Partners (CHP) in rural Kenya, collecting data by digitizing thousands of children’s handwritten immunization records to analyze trends in immunization rates. CHP is a Kenyan non-profit which operates four clinics in predominantly Maasai communities: Ewaso-Ngiro, Mara Rianta, Aitong, and Talek. My co-fellow, Evey Thompson, and I worked with GRI’s Ignite Global Health Lab, who in partnership with CHP, began collecting this immunization data in 2019. We traveled to each clinic location to create a comprehensive dataset that spans from 2016-2023 across the three locations.

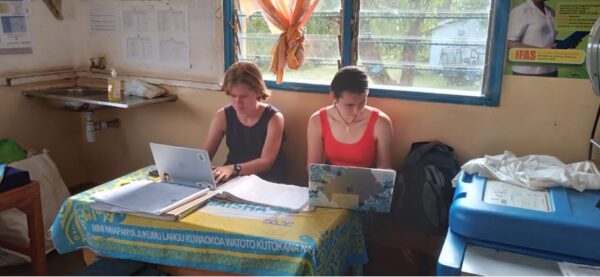

The set-up for a usual day of data collection, or: the reality of typing thousands of immunization records into Excel.

Over the course of six weeks, we updated 2,000 records and collected over 6,000 new records. We are currently using this data, which spans seven years, to analyze geographical and immunization timeliness trends. In addition, we conducted an ethnographic study by maintaining a daily log of field notes as we operated as both data collectors and quasi-interns for CHP. From our observations, we identified potential obstacles to timely vaccination and effective record keeping. For example, paper records are often left blank or inconsistent on busy days, and it is difficult to contact patients who fail to show up at vaccine appointments. These problems could be solved with electronic recordkeeping, but CHP currently lacks the funding and infrastructure for those improvements. As we continue our research, we hope to reveal immunization trends and present suggestions for improving immunization processes in the rural setting.

The best aspects of my time with CHP were the people. Each clinic has its own tight knit community of nurses, clinical officers, administrative workers, leadership, cleaners, and someone who provides tea (and chapati). I quickly left my fear of lack of community behind.

Within our first week in Ewaso Ngiro, we were invited to walk home with a nurse who had been asked to show us around. She invited us into her home, poured us tea, kindly gave each of us necklaces made by her mother-in-law, showed us her goats, and introduced us to her son. Late one night, a neighbor knocked on our door with the gift of freshly made chapati.

A Fourth of July lunch of nyama choma (roast meat), chapati, and sodas. A time of celebration with the Aitong clinic community.

These acts of welcome continued through the summer; several times, we were invited over for tea, for dinner, and sent home with kind gifts. But those interactions weren’t the ones that mattered most; it was the day-to-day chats with coworkers, raucous laughter during tea time in the morning, and joking around as we got to know one another that made me feel welcome. Through building those relationships, we learned about our new friends’ lives, relationships, work, opinions, and struggles. We were asked countless serious (and silly) questions about life in the U.S., and what I emphasized in those conversations rang true the whole summer: Things aren’t as different as both sides may think. Both in the U.S. and Kenya, we have very poor and very rich folks. Not everyone in the U.S. has an iPhone either — yes, we have very wealthy citizens, but most people aren’t as rich as you think.

In Aitong, we became close with Joshua, the man in charge of the clinic, a former NOLS (National Outdoor Leadership School) instructor, an incredibly funny guy, and of course, a proud Maasai. We stayed in a hotel there, and most nights Joshua would pop in to eat dinner with us. Through those dinners, we learned so much — about CHP, his life, and cross-cultural exchange.

Joshua’s perspective on cross cultural understanding sticks with me. He described how western perceptions of Africa are often riddled with fear and lack of understanding. My sister’s fear of hippos was a perfect example. When you haven’t experienced something, it’s unknown and often scary. Sitting at home in the U.S., it’s easy to be fearful of the snakes, hippos, or the different conditions in which people exist.

But upon having an experience like ours this summer, you understand that people are just people, you might only see one snake in the wild, and watching hippos from the riverbank with adored coworkers is just something to do after work. Joshua’s point was this: Everything that’s scary and intimidating sitting at home is just life there. And I agreed. That’s just one reason that such an immersive cross-cultural experience is so important.

Presenting preliminary analysis of the immunization data to CHP leadership at the end of July.

We also discussed Kenyan perceptions of the U.S. Most people we talked to assumed everyone in the U.S. was incredibly, celebrity-level wealthy. In conversation, Joshua similarly did his best to explain that things really aren’t all that different. I respect his understanding of both ways of living and the way he communicates the similarities and differences.

As one of the original CHP workers, Joshua also educated us about methods of health education in rural Maasailand. I asked about immunization, since our summer was dedicated to the topic, and the way he communicated the importance of childhood vaccinations with Maasai families felt brilliant. The answer went something like “You put doors and windows on your house to keep out the hyenas and lions. Children need vaccinations like the house needs doors, to keep out the diseases which are like hyenas and lions to the body.”

Such a description illustrates — not only for families skeptical of vaccines, but for everyone — the importance of childhood immunizations. I see it as a motivation for the work we continue to do in conjunction with CHP. I am excited to continue analysis of the data we spent the summer collecting, and to educate others on the importance of health education, of electronic record keeping, and healthcare accessibility.

Thank you Katie for this excellent commentary on your work to track childhood immunizations in Maasai communities. My husband and I visited a Maasai village and our experience was profoundly moving. The scarcity of water impacts every aspect of their lives, and yet the mud huts were clean, the beaded necklaces beautiful, and the smiles sincere. We were changed, and I’m sure you were too. The true beneficiaries, of course, are the children. Kudos to you and your program!