Future Directions in Military Assistance: Analyzing the Role of Intercultural Competence

By Lilly Doninger ’24

This post features a student’s reflections on “The Past, Present, and Future of U.S. Alliances,” a conference recently hosted by GRI’s Security & Foreign Policy Initiative. Student attendees had the chance to share personal insights, interpretations, and potential paths forward in these reflections. Any views expressed pertain to the authors themselves and not to the Global Research Institute.

Military assistance programs are undeniably important components of U.S. alliances. “The Past, Present, and Future of U.S. Alliances Conference” highlighted several aspects of current U.S. aid. The U.S. currently gives some kind of security force assistance to nearly every country in the world in an attempt to limit the potential for future involvement. This aid rarely looks like weapons systems and hard military equipment sitting in countries without U.S. troop presence or a training component. While we essentially do this everywhere in the world at a relatively cheap cost, U.S. military assistance is usually considered unsuccessful.

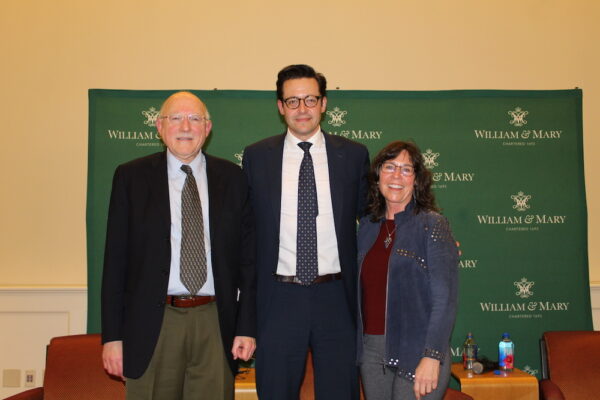

The keynote conversation brought together Barry Posen (left), Kori Schake (right), and Mark Hannah (center) to discuss modern alliance frameworks, U.S. perspectives, European dynamics, and more.

The “Future Directions in U.S. Military Assistance” was an excellent panel featuring Mariya Omelicheva, Rachel Tecott Metz, Joshua Alley, and Security & Foreign Policy Initiative Director Jessica Trisko Darden. I immediately took particular interest in this panel, as it was the only panel that specifically focused on the military arm of U.S. alliances, and it was one of the only sessions dominated by women. The women in this panel held relatively different views on U.S. military assistance when it comes to U.S. alliance policy. Professor Mariya Omelicheva asserted that the wide scope of U.S. military assistance should “extend, not contract” to further provide comprehensive training and education efforts to the forces with which we currently partner. At one point in the discussion, she also suggested that the U.S. take more of a leadership role in U.N. peacekeeping missions with a greater military assistance posture. Professor Rachel Tecott Metz disagreed, positing that the U.S. should draw back current military assistance programs to focus on allies and countries where there are specific and pertinent defense needs. The panel generally agreed that the U.S. military has taken on a “constructivist view” of its role in the world and has asserted itself as “norm entrepreneurs.” Additionally, the consensus was that the current U.S. military assistance efforts are largely ineffective.

Student attendees shared insights and takeaways with one another.

I subscribe to realism, and I hope to pursue a career in military strategy. However, I believe that a crucial point of failure in relation to U.S. military assistance is and has been a consistent lack of cultural understanding and adaptive planning. Rachel identified a key area of weakness with military assistance: military personnel and advisors are the ones who are tasked with the management and partnership of alliances and these peripheral aid missions. As Craig Whitlock asserts in The Afghanistan Papers: A Secret History of the War, a key lesson learned from the U.S. war in Afghanistan was the lack of cultural competency fueled by a fundamental lack of State Department personnel and military anthropologists. The U.S. often tries to recreate its command structure and military doctrine in countries where there are not even formal government institutions and accountability mechanisms (Tecott Metz).

I argue that the U.S. should extend our training and educational programs as the key mechanism of U.S. military assistance to the countries that we currently support. Identified countries with specific defense needs (i.e. special forces training) should continue to be the priority for more specialized training and harder forms of aid. The State Department and other agencies should develop key strategies based on the cultural norms and values held by the receiving countries. I believe that U.S. military assistance should require both greater collaboration with local forces and greater strategic planning to account for cultural differences. Beyond the specific scope of U.S. security force assistance, the U.S. should more greatly emphasize cultural competency and critical thinking in training and courses for the armed services.

No comments.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.