From Ideas to Impact: How a Multidisciplinary Team Tracked Government Responsiveness

This is the first installment of a series highlighting exceptional student contributions to the Global Research Institute. Stay tuned for other features throughout April: Undergraduate Research Month.

As GRI advances critical, policy-relevant projects, its researchers unite in pursuit of shared goals—even when they might bring different perspectives or experience to their roles. Such was the case at GRI’s Global Cities and Digital Democracies Initiative, when first-year student Anna Glass ’24 collaborated with Rahul Truter and Isabel Arnade, who are both pursuing a Master of Science in Business Analytics at the university.

The team worked with Dr. Tanu Kumar, a GRI Post-Doctoral Fellow for Academic Diversity who works with both AidData and the Center for African Development. The researchers assessed complaint and response data from the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai, observing key disparities in how the government addressed a range of issues.

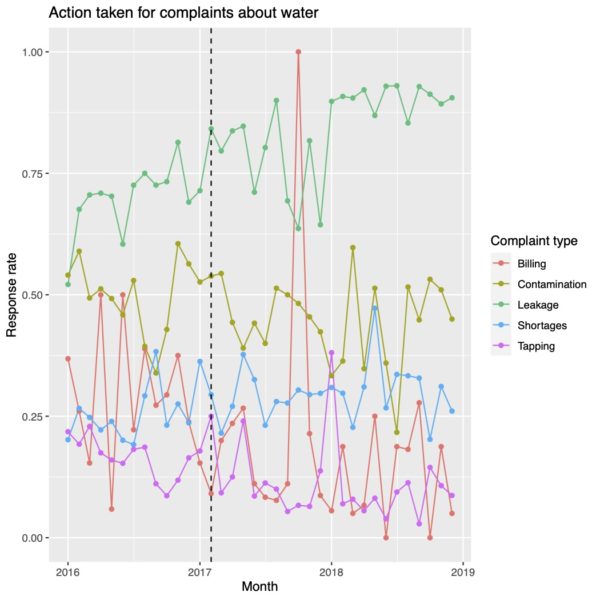

“We found that they were much more likely to respond to complaints concerning water supply, such as shortages or contamination, and they were far less likely to respond to complaints about the unauthorized tapping of water,” Glass said. “We speculated that this was because the government of Mumbai does not want to take a water source away from somebody in need, so they’re more reluctant to respond to complaints where they would be removing a source of water from a person, but more likely to respond quickly to complaints that would return water to a person or prevent them from drinking contaminated water.”

Truter said observations such as this were made possible through actionable steps and ongoing collaboration. First, he and his partners categorized both the response and complaint data, and then, they created a classification algorithm so that a model could predict what category a certain complaint would fall under.

“We had to actually train the algorithm in R Studio, so what we did was create a manual classification,” he said. “We would pick words from the citizens’ complaints and see how often they appeared and see how that was correlated to a certain kind of classification.

Along the way, Truter said, his teammates innovated and found ways to streamline the process.

“It’s kind of tedious to comb through thousands of lines of data to see what’s associated with what, so we used something called a lasso model, which is a binary prediction system to evaluate what degree or coefficient each keyword—such as burst pipeline or action taken—is associated with a certain category,” he said. “That made life a lot easier for us because instead of manually going through all of the data, we would just have to create the lasso model, type in whatever category abbreviation we were looking for, and see what words came up and how significant each of those words were to predicting the classification.”

As displayed in the researchers’ chart, government responsiveness varied across time based on the category of complaint.

Building the algorithm, Arnade said, fostered trust among the researchers, since many detailed steps, revisions, and decisions contributed to the final product.

“What we were trying to do with the algorithm we were building was to minimize the error rate, and we did that using only a smaller subset of data,” Arnade said. “In the first model we built, for one of the categories, we got to an eight percent error rate, and Dr. Kumar told us she was able to apply that to a huge data set of 20,000 rows of data and keep that minimized error rate. It was surprising to me how that algorithm could be applied on such a large level.”

Truter credited the team’s progress to its open lines of communication and willingness to share ideas.

“[Anna and Isabel] are really in tune with what’s going on, and they had amazing insights to share that really helped me out along the way,” he said. “We were all somewhat new to R, but from the way they went about their experiences, I couldn’t even say that. It felt like they really knew what was going on. We all needed to be on the same page of what to classify things as because if we didn’t do it properly, then we’re going to have a lot of misclassifications—not because of model error, but because of human error.”

The scope of GRI research often involves longer-term participation, which Arnade said provides participants with time to build comprehensive knowledge and community.

“I had done a lot of group projects inside the classroom at William & Mary, but I think this is a different experience because it’s an extended project,” Arnade said. “You can kind of become an expert on a little bit of work.”

Glass said the team’s different ages and area of study contributed to its success, since she remained open to mentorship and guidance—not only from Truter and Arnade in meetings and through a group chat, but also from faculty advisor Dr. Tanu Kumar.

“I know the Global Research Institute is all about turning ideas into impact, and I think Dr. Kumar has done a really amazing job creating a project idea that does exactly that,” Glass said. “We were working off of this hypothesis that although many complaints were marked as closed or attended, in reality there were more inefficiencies in the government or complaints that weren’t attended.”

Moving forward, Truter said he sees clear applications for his team’s research. The team’s final report is still being finalized, but GRI will post when it’s available.

“The ideal outcome is definitely that the registration system is … inspected more carefully,” he said. “This model can also be improved. With all the data the government has and all the resources they have, this is something that could be used to make a ton of information easy to interpret. I would definitely like the government to use it to see where they’re having the most issues and where they can allocate resources to fix these issues.”

No comments.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.