Mount William & Mary, Really?

Last week William & Mary News published a story about a second campaign to officially name a peak in the Rocky Mountains of central Colorado Mount William & Mary. The mountain in question is a subordinate peak on Mount Elbert, the highest summit in the Rockies, that tops out at an elevation of 14,440’ (4,401 m) above mean sea level. The Geology Department regularly visits central Colorado as part of our Regional Field Geology course, and with William & Mary students I’ve been privileged to summit both Mount Elbert and the proposed Mount William & Mary on multiple occasions. Mount Elbert is a gentle giant that rises above the upper Arkansas River valley, the scenery is delightful, and there is much geology to see on Elbert’s rocky ramparts.

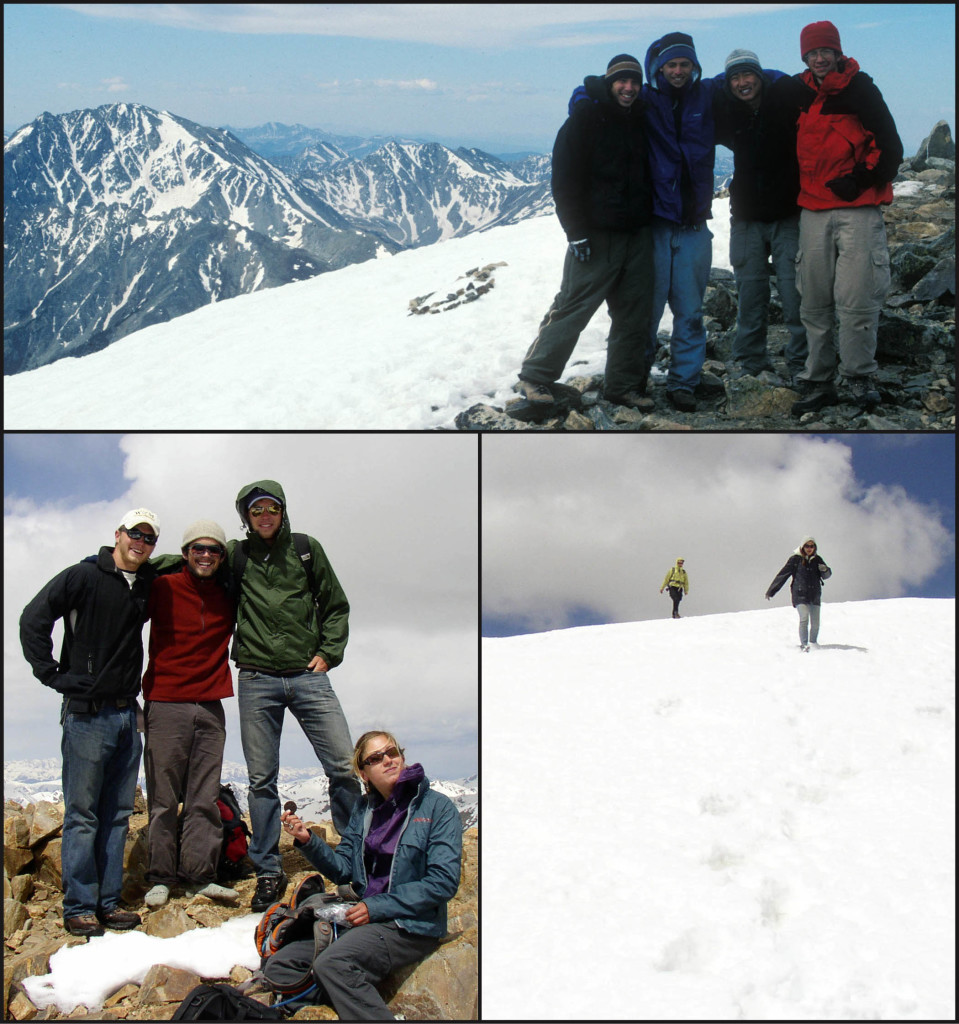

Rocky Mountain high in Colorado, William & Mary geologists at Mount Elbert. Top: Chris Koteas, Twohy Murray, Brian Hasty, and Chris Coppinger (from left to right) huddled up on the summit in 2002. Lower Left: Brendan Murphy, a shoeless Trevor Buckley, Drew Laskowski and Autumn Millslagle (from left to right) on the summit in 2008. Lower Right: Ali Snell and Beth DeGiorgis descending a snowfield near the summit. (CMB photos).

Taylor Reveley, William & Mary’s president, sent a missive to W&M alums residing in Colorado seeking their support in the effort to name Mount William & Mary. The premise being 1) a presumed connection between William & Mary and the Colorado Rockies, forged primarily by the Louisiana Purchase which was ginned up by W&M alums, Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe back in 1803; 2) other universities have their monikers on Colorado peaks, so why shouldn’t William & Mary join that club?; and 3) faculty in the Kinesiology department have, at times, conducted high-altitude physiological research on the mountain.

Over the past week a number of geology alums have contacted me, asking about my views on a possible Mount William & Mary (a mountain that some of us have climbed together during Geology field courses). Here it goes!

I do not support this effort: the campaign to name a Colorado peak Mount William & Mary is misguided folly.

My reasons are as follows:

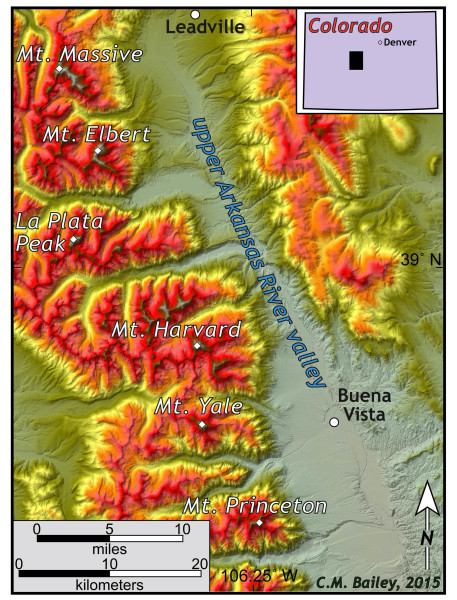

Shaded relief map of the Sawatch Range, Collegiate Peaks area, and the upper Arkansas River valley, central Colorado.

The Hegemony of Geographic Naming

Geographic features often acquire their given names by curious means, but the history of exploration into a region is typically important in the naming process. Like it or not, being there first counts.

Mt. Elbert is named for Samuel Elbert, a Colorado territorial governor appointed by Ulysses S. Grant in 1873. To the south of Mt. Elbert lies the Collegiate Peaks whose naming stems from an 1869 field expedition led by Harvard Geology Professor Josiah Dwight Whitney. His expedition included four young Harvard lads and support staff, their purpose was to explore central Colorado and along the way measure the altitude of the higher peaks. During that trip, the party named two high peaks for Harvard and Yale (Whitney’s alma mater). Over the ensuing decades other peaks in the area were named for prominent, albeit distant, universities (Columbia, Princeton, and Oxford).

In the late 19th century William & Mary was in a bad way. The Civil War had devastated the College; it was bankrupt both literally and intellectually. William & Mary sent no scientific parties west to the Rockies during that era of exploration and, therefore, played no role in the naming of the western landscape. It wasn’t until a century later (the 1970s) that Geology Professor Jerre Johnson first led W&M students on field forays to the American West; by that time the glory days of place naming were long past. However, the value of those field courses continues, and in the modern era William & Mary geologists are conducting research from the deserts of California to the high peaks in the Colorado Rockies.

As an academic institution William & Mary has a venerable history. But let’s be honest, our connections to the American West, were until the late 20th century, pretty much non-existent. To claim otherwise stretches credibility.

Coloradans Don’t Care for Carpetbaggers

Colorado claims more than 50 peaks that exceed 14,000 feet in the elevation. They are known as “fourteeners.” Their names range from descriptive (Maroon Peak, Pyramid Peak, Mount Massive) to those honoring prominent 19th century figures (Mt. Lincoln, Kit Carson Peak) as well as native chiefs (Mt. Shavano, Mt. Antero).

Interestingly, there is a long history of attempts to rename Colorado’s prominent “fourteeners.” For instance, Mount Massive, which stands southwest of Leadville, has endured multiple attempts to change its name: in 1901 there was an effort to rename it Mount McKinley (McKinley’s name adorns a famous mountain in Alaska), and in 1965 another effort sought to rename the peak Mount Churchill (in honor of Winston Churchill). These efforts were not successful, in part, due to local sentiment.

In 1998, William & Mary Kinesiology professor Ken Kambis filed a petition with the U.S. Board of Geographic Names to register Mount Elbert’s unnamed south peak as Mount William & Mary. The Colorado Mountain Club vigorously opposed Kambis’ petition, and ultimately the U.S. Board of Geographic Names turned down the request.

Colorado’s glorious mountains draw people to the state from all over (during the summer months, Texas license plates commonly outnumber Colorado license plates in many mountain towns). Understandably, Coloradans are leery of outsiders renaming their mountains. The effort to name this South Elbert is already being lampooned by some and will no doubt draw the ire of many Coloradans.

In years to come, on W&M geology field trips to Colorado, I’d hate to be branded “a carpetbagger from back East, whose school put their name on Mount Elbert’s south peak”.

This naming effort seems a curious case of misplaced academic hubris, it does not fit the William & Mary ethos.

William & Mary Deserves Better than a Subpeak

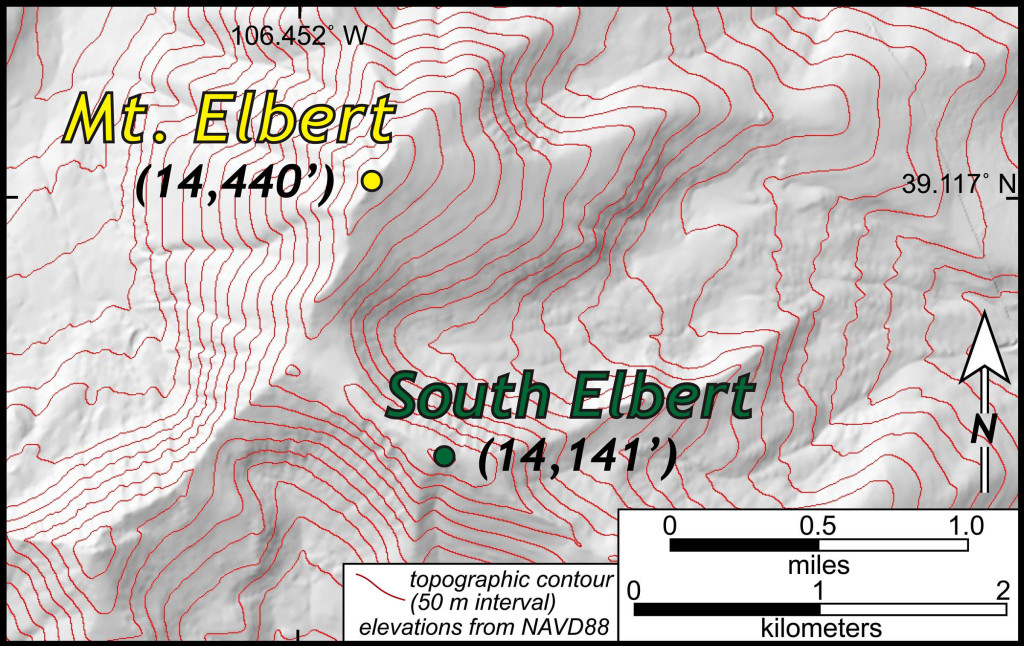

The latest petition to the Board of Geographic Names seeks to name a 14,141’ (4,308 m) high point, on the southeastern flank of Mount Elbert, as Mount William & Mary. On the U.S. Geological Survey topographic map of the area there is no name for this geographic feature; the Colorado Mountain Club, most mountaineering publications, and many locals call it “South Elbert.” Although the peak exceeds 14,000 feet in elevation, it’s not recognized as a “fourteener” because the elevation drop between this high point and the main peak (Mount Elbert) is less than the requisite 300 feet (91 m) to be considered a separate peak.

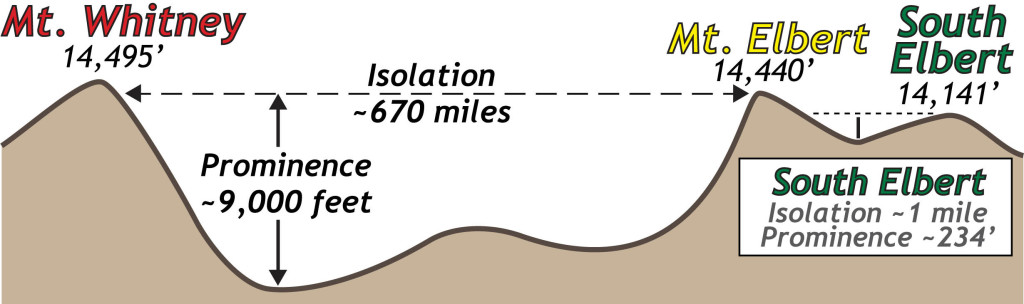

There is an established, and somewhat arcane, vernacular related to the significance of mountain peaks. Two parameters include: topographic isolation and topographic prominence. Topographic isolation is simply the great circle distance between the peak and the nearest point of equal elevation. Mount Elbert is the highest summit in the Rockies and it’s topographic isolation is a whopping ~670 miles (~1,080 km) that’s the distance to the slightly taller Mount Whitney (named for the aforementioned Josiah Dwight Whitney) in California. Topographic prominence is the vertical distance between the high point and the lowest contour that encircles it and no higher summit. Mount Elbert’s prominence is just over 9,000 feet (2,770 m). The topographic isolation of the South Elbert high point (the proposed Mount William & Mary) is a paltry mile (1.6 km) and its topographic prominence is a modest 234’ (71 m). By way of comparison, the 5,729 foot (1,740 m) tall Mount Rogers (Virginia’s highest mountain named for William & Mary educated William Bartram Rogers) has a topographic isolation of 40 miles (~65 km) and a prominence of 2,500 feet (~760 m).

The above is perhaps a long-winded statement. Its intent is to demonstrate that the presumptive Mount William & Mary is a just subpeak. While the south peak on Mount Elbert is a lovely piece of Rocky Mountain real estate, it is not a distinctive or significant highpoint in its own right.

Why would a presumably erudite and respected institution like William & Mary want its name associated with a minor topographic prominence?

A peak of prominence? View to the south of the proposed Mount William & Mary from the upper reaches of the taller Mount Elbert. (CMB photo)

No doubt some will take my comments as those of a wayward curmudgeon without an ounce of Tribe Pride. I’m a 1989 graduate of the College and proud of William & Mary–suit me up in the Griffin costume and I’ll lead a cheer.

At William & Mary I learned the value of both critical thinking and careful research. In this case I don’t see much of either, there aren’t many legitimate reasons for William & Mary to attach its name to a minor Rocky Mountain summit. Surely, Coloradans will be laughing about William & Mary’s folly, especially if the College successfully gets its name affixed to a summit that’s not even the highest point on the mountain.

______________________________________

To learn more about the history of place naming in the United States read: Names on the Land by George R. Stewart (1967)

For an excellent book on Colorado mountains read: A Climbing Guide to Colorado’s Fourteeners by Walter R. Borneman and Lyndon J. Lampert (1978)

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.

Prof. Bailey:

I appreciate your opinion on the matter of naming an unnamed geographic feature in Lake County Colorado in honor of the College of William & Mary. While I expect some modicum of discontent from locals in Colorado, I am surprised and saddened that it also can come from within. Your disagreement with President Reveley is indeed your privilege but I do believe that such declarations should be, as you state, based on “critical thinking” and “careful research.”

Please allow me to provide some information that your blog readers may find useful as they apply the “critical thinking” phase of decision making. First, you need not fear being called a “carpetbagger from back East” because the proponent of the application to the U.S. Board on (not “of” but you are forgiven in that the USBGN says this is the most common mistake made regarding their correct name) Geographic Names is a Colorado native and lifetime resident who happens to have great admiration and commitment to the College of William & Mary. Second, the “presumed” historic relationship between the “ginned up” as you refer to it, Louisiana Purchase of what is all of Lake County (wherein Mount William & Mary is located) and most of Colorado is significant enough for Denver’s History Colorado Museum to acknowledge the 1803 purchase as a signal important event in Colorado’s evolution. Far be it for me to have the “hubris” to claim I know more about Colorado’s history than does History Colorado (formerly the Colorado Historical Society). I only use facts that are, in this case, readily available upon light research. Fourth, I am delighted that you and others in the Geology department have used the Mount Elbert area for research multiple times since the 1970’s. In my opinion, field research and exploration are great ways to teach in that they can give real meaning to classroom and laboratory instruction. It also makes the case for a “connection” between Lake County and Mount William & Mary even stronger. By the way, a foundation I am affiliated with (the foundation has no association with William & Mary) funds trail maintenance in the Mount Elbert area through the Colorado Fourteener Initiative (CFI). This annual gift is to cover any damage caused by increased foot traffic due to my research. I hope that academic departments at W&M (and elsewhere) consider doing the same if they do not already support trail maintenance in areas impacted by their presence. Fifth, the naming of the Collegiate Peaks and other mountains named after universities or colleges is expertly reviewed in an article by Merritt Blakeslee published in The Journal of the Colorado Historical Society, Number 15, 2008 p. 83-127. This will give anyone a detailed description of how those names came to be. It does not cover the naming of Mount Elbert though. By finding and reading an article by Ed Quillen published in 1998, one would note that Samuel Hitt Elbert was indeed appointed territorial governor by President Grant in 1873 and was un-appointed by Grant less than one year later. One reason being that Elbert broke a treaty with the Ute nation and thus allowed miners (Elbert and his son had financial interests in the mining industry) access to mine over 3 million acres of Ute reservation land. Elbert had the mountain named in his honor by a group of these grateful miners. A number of my friends and acquaintances in Lake County, CO would love to have the local use of “South Elbert” eliminated. I would think the Ute nation would also be in favor of calling it anything other than Elbert. Sixth, it seems that calling the naming of Mount William & Mary “a curious case of misplaced academic hubris…(that) does not fit the William & Mary ethos” then going on to make a case of William & Mary deserving something better than a sub-peak is a bit confusing at best. Your description of an established (a citation would be helpful) vernacular related to the significance of mountain peaks is informative although not an issue here. This is because the USBGN does not recognize any such requirement. The names mount, mountain, hill, hillock, summit, peak, etc. are not governed at the federal level by distance from surrounding points or prominence. That said, the Colorado Mountain Club does have criteria of a 0.5-mile distance from, in this case Mount Elbert, which you noted was 1.0 mile away, and they now have a 500’ prominence requirement. The CMC did oppose my 1998 application but the opposition was due to the lack of a “significant association with Colorado.” In fact, the chair of the Toponymics Committee of the CMC went on to say the CMC “would look favorably upon proposals to change the names of subsidiary high points, such as South Elbert, only if the proposed name had a significant association with Colorado.” Of course we do have a significant relationship with Colorado due to the “ginned up” Louisiana Purchase a well as because of many other reasons. Nothing in the 1998 CMC letter of opposition mentioned prominence or isolation. In fact, of the 54 CMC “fourteeners” (Peakbagger.com) eight of them do not meet the present 500’ CMC requirement and one, North Maroon Peak, has a prominence of 219’ which is less than the 234’ prominence of Mount William & Mary. Therefore, for clarification, the CMC does recognize “fourteeners” with elevation drops of less than 300’ but I am delighted that what is locally known as “South Elbert” has never been named and hopefully will never be considered by the CMC as the 55th “fourteener.”

Seventh and eighth, the Department of Kinesiology & Health Sciences is developing a summer course in environmental sustainability to be taught in Leadville on the Colorado Mountain College campus and on Mount William & Mary. In addition, the Lake County/Leadville Economic Development Corporation is very interested in convening an international conference on high-altitude medicine in collaboration with our W&M altitude physiology lab and others to draw attention to Leadville as a center for high-altitude medical research and information.

I could continue this unfortunately long clarification but instead encourage your blog readers to reach out to me at any time to discuss this matter and to consider writing the Colorado Board on Geographic Names in support of this initiative at 1313 Sherman Street, Room 120, Denver, CO 80203-2274. Thanks for the opportunity to comment on some of your criticisms of President Reveley’s missive to our Colorado alumni.

I believe the mtn in question was in mexico not the treaty area you suggest. See the Adam Onis treaty about the boundary and the Arkansas river

I must say I find it sad that any professor here at the College would be saddened, and indeed discouraged, by any sort of internal debate that is taking place here at William and Mary. This is an environment in which we seek to sow the seeds of independent thinking within our student body and surrounding community, and the fact that disagreement has arisen over this issue is perfectly natural.

Furthermore, this campaign seems a bit strange if you ask anyone around campus. Personally, I feel like we should focus more on achieving greatness in academics and the arts, rather than fruitlessly striving for such a trivial achievement such as deciding to name a “mountain” after ourselves. Lest anyone say indignantly in response “There are Ivy League mountains nearby, and William and Mary is a good college too!” let us to note that the surrounding mountains were named as such as the first people to climb these peaks were from those respective colleges… a fact that was promptly relayed to me by members of these respective institutions when they caught wind of this story. Thinking of renaming a “mountain” simply because we have plans to establish a field course to take place on the peak, is a rather self-contrived and vain act (at least to the vast majority of on-lookers).

All in all this campaign seems to be creating bad press for the college, and I think it would be wise to distance ourselves from this effort lest we create more bad press for ourselves. There are much better uses of our time than researching the history of the name-sake of a “mountain” in Colorado, unless you have created a unique history-geology double major.

If names perceived to honor to Mr. Elbert seem unpalatable after slights against the Ute nation,maybe a name chosen by the Ute people might be better suited?

A few field trips and a Kevin Bacon-esque connection between the mountain and the college might establish some relationship between W&M and the land in question, but it is a difficult case to suggest that our connection is greater than that of the original locals. (Do they even care what the mountain’s called, has anyone asked? Did they already have a name for it anyway?)

Chuck,

I don’t discredit the value of critical thinking and careful research I learned at William & Mary, largely through the Geology department, but for me Ken Kambis’ campaign simply appeals to passion.

The depth and breadth of William & Mary’s connections to Colorado may be debated. Ginned up or not, Jefferson’s land grab opened the West and kicked off years of American exploration. I like to believe that Jefferson’s College education put him in a position, as President, to make such a purchase. I further believe that the history and science Jefferson learned while in Williamsburg motivated him to explore, if not personally, the West. It did for me.

My education, especially my experience with the Geology department, gave me the desire and opportunity to make Colorado my home. I am proud to live here and I am proud to have graduated from William & Mary. For me, this is enough of a connection to support Mount William & Mary. I would be thrilled to see the name of my alma mater stamped on one of the giants of the Sawatch Range, where even the subpeaks are impressive.

As for those leery Coloradans – they are unlikely to be affected by such a name change, if they notice at all. Locals in these mountain towns are stuck in their ways, but such renaming will not draw ire. Those who call this peak “South Elbert” will continue to do so in the future, shrugging off a name they’ll only see on maps and the occasional trailhead. But amongst outsiders who buy those maps and visit these mountains, William & Mary will gain prominence in a region where many do not recognize the name of our school.

Chuck, we’ve largely missed the era of naming major peaks on this planet. I do not see the renaming of this peak as a slight to William & Mary’s reputation. Summiting Mount William & Mary would remain an impressive feat. For many, it is the first significant accomplishment on the way to something bigger. As a Coloradan, I am happy to support this campaign. I encourage other alumni living in Colorado to do the same.

Matt Sparacino, ’12

Steamboat Springs, CO

I need to get a couple things out of the way here:

1) Internal debate here at William & Mary is not something that should ‘sadden’ anyone; rather it should be embraced and even applauded. Disagreeing with President Reveley’s standpoint on this saga of geographic naming is absolutely not a ‘privilege’- it is a right held by all those who wish to voice their opinion on this matter.

2) I don’t think this is the appropriate platform to jab other departments’ ‘trail maintenance’ funding. This is another item of concern entirely and should not be used to minimize other efforts departments may take to ‘leave no trace’ while conducting field research.

I am a proud 2014 graduate from the Geology department at William and Mary, and I wholeheartedly am against the renaming of South Elbert. I don’t believe that just because a few of the proponents for the application are Colorado natives and residents implies that a large majority of the locals will not be opposed. The Louisiana Purchase seems to be the main reason behind the naming of South Elbert, so what’s stopping William and Mary from naming any geographic feature held within the domain of the Louisiana Purchase territory? Just because you choose a certain location for academic research, it does not entitle your affiliated institution at large to a special connection with that area. The Leadville natives are their own people, and I’m sure they could think of a more meaningful name enriched with historical, local significance that fills THEM with a sense of pride- not us.

I am sure William & Mary deserves a lot of things, but naming a mountain in Colorado many of us had never heard of to begin with, is probably not one of them. If naming a geographic feature is something the collective body of William & Mary feels strongly about, shouldn’t it be up to us where/what it is? Shouldn’t we have been informed of this desire and petition long before that decision was even made? I, for one, cannot get behind such a seemingly random effort.

How about if we named it The Mountain of William and Mary in Colorado?

But, don’t you think we should try to make it longer? Does anyone know the maximum possible character limit for a geographic name? We should definitely max it out.

I’m thankful for Professor Ken Kambis’ clarification on a number of points regarding my post on why I oppose William & Mary’s effort to name a mountain in Colorado- Mount William & Mary. I’ll keep my reply to a digestible portion.

Professor Kambis seems to be out-of-sorts by my use of the phrase “ginned up” in regard to the Louisiana Purchase. Ginned up is not necessarily a pejorative (just ask any martini aficionado). Thomas Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase was of paramount importance to the western expansion of the United States, and my comments were in no way intended to denigrate that achievement.

I question that the logic asserting Lake County, Colorado, which was part of the Louisiana Purchase orchestrated by Jefferson, a William & Mary alum, creates a special/unique relationship between William & Mary and Colorado. As I wrote earlier that assertion stretches credibility. Coloradans think William & Mary is somewhere between arrogant and misguided for making such a claim. As one Coloradan noted to me, “…it’s laughable, in a sort of blue-blood patrician way, let us name a mountain for the good ole’ Tribe shall we…”

School spirit aside, William & Mary’s quest to name a Colorado mountain for itself is a bad idea.

As a Colorado resident who lives 20 miles from South Elbert, I find Chuck’s arguments more convincing and his predictions of Coloradan reactions more accurate. Chelsea makes a good point too.