A Frenzy of Fall Field Trips 2: Flowing Low and Flying High

Earlier this summer I reported on the Gladstone Gladiators’ ‘games’ on and over the James River, all part of our research campaign to decipher and map the geology in the central Virginia Piedmont. On that trip, we used a drone to acquire aerial imagery of rock structures exposed in the river bottom while we paddled canoes down the James River on a summer day.

Our July research trip was a conceptual success, but the James River conspired against us as the river waters rose nearly 20 cm (8”) the night before we headed to the river. That extra water covered more of the bedrock than was ideal, and the water was a tad turbid making it difficult to see through the water column. We needed another trip at low flow to obtain better imagery.

Little to no precipitation fell in central Virginia during August and early September, and river levels were at their lowest of the year. With these late summer conditions, we set out for another float trip on Sunday, Sept. 15th. Dr. Shannon White (and a licensed ROV pilot) from William & Mary’s Center for Geospatial Analysis volunteered to fly the drone (a DJI Phantom 4 Pro), and assist Sam Belding as he collected more data for his senior thesis.

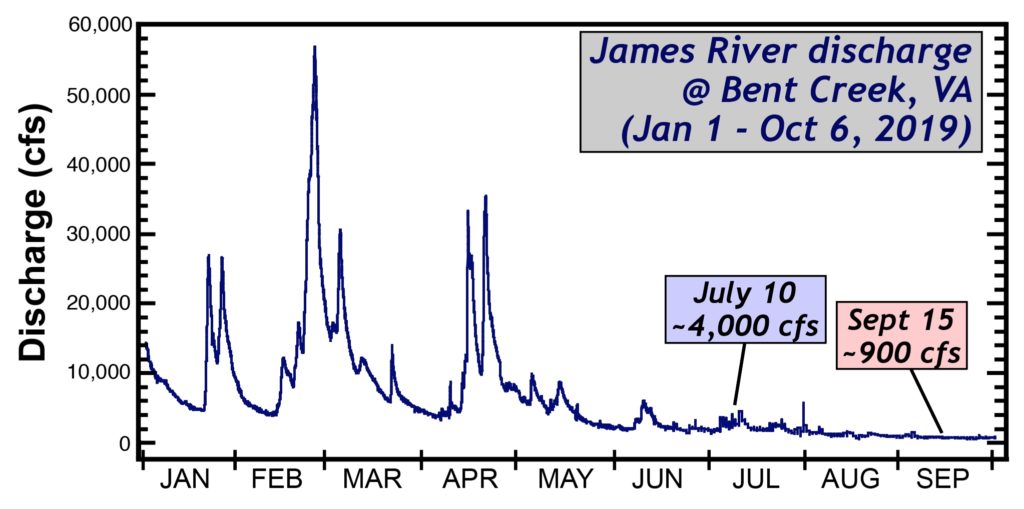

We launched canoes at Bent Creek, a small riverside community in Appomattox County. Across the river, the U.S. Geological Survey maintains a river gauge so we knew exactly what conditions we’d find. We set off as the James flowed at a rate of ~900 cubic feet per second. During our July 10th trip, the river coursed along at nearly ~4000 cubic feet per second. That amounts to a difference of nearly 25 cm (~10”) in the water level.

James River’s discharge at Bent Creek, Virginia (Jan. 1 to Oct. 6 2019). Note the ever-declining flows during the past two months during which there has been little to no precipitation. This pattern is a typical one for the James River during the course of a year. cfs- cubic feet per second. Data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

As Shannon and Sam worked the drone, Bianca Boggs and I collected rock samples while the drone buzzed overhead.

Top left: Geology senior Sam Belding awaits the drone’s return. Top right: Dr. Shannon White at the controls sending the drone skyward. Bottom: Geology technician Bianca Boggs (W&M Geology ’19) frames up an outcrop of feldspathic gneiss.

The lower water level made a difference. Not only was the bedrock far more emergent, we could also see the details of the channel bottom to depths of >1-meter (3.3’). We’ve now got two sets of images, taken at different water levels, to compare. Going forward, I see the potential for more repeat imagery at the same location to analyze both geological and ecosystem changes through time.

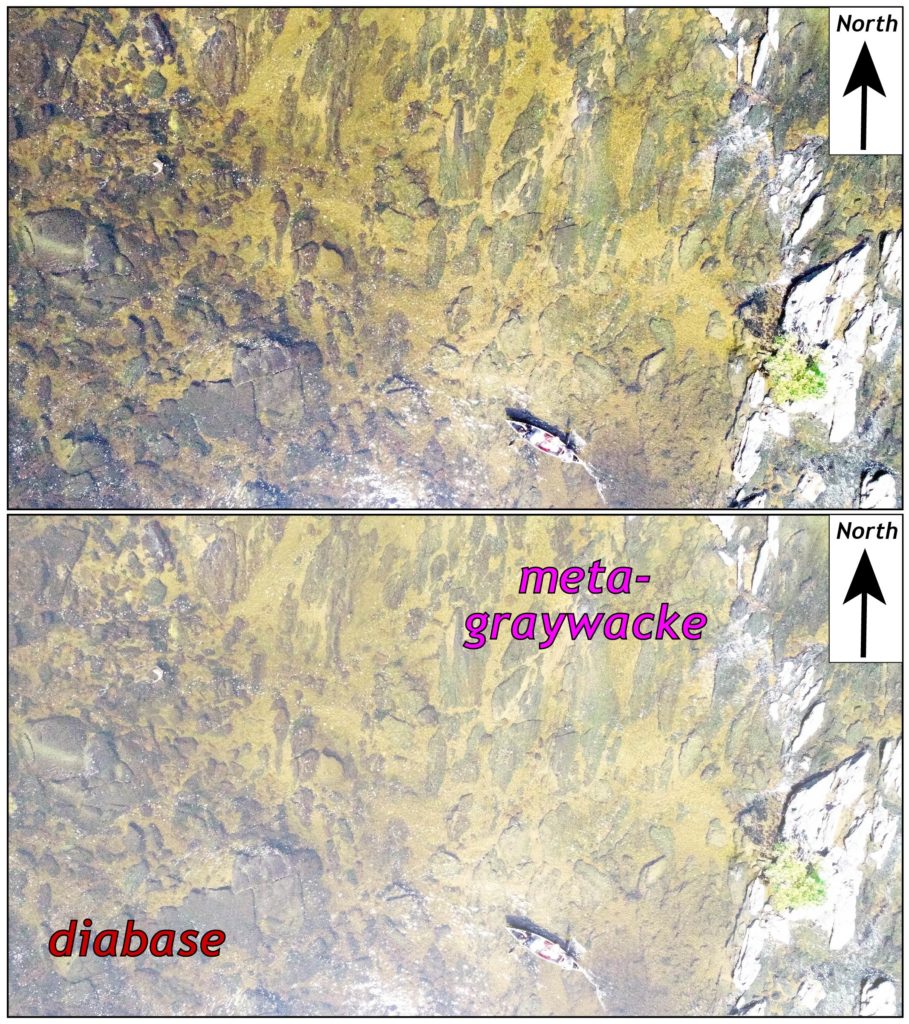

Two drone images of the same location, the upstream tip of an alluvial island in the James River, 2 km downstream from Bent Creek, Virginia. The canoe(s) are on a vegetated gravelly sandbar. In the July 10th image, only vague details of the river bottom are discernible, whereas in the September 15th image sediment, vegetation, and bedrock structure are readily visible. The river flows from south to north, and the canoe(s) are ~4.5 meter in length.

In the image below there is much to see, including a diabase dike that’s in contact with an older graywacke (originally a muddy sandstone) that’s been metamorphosed and deformed. Just where is the contact between these distinctive rocks of vastly different age?

Can you find the geological contact between the diabase and metagraywacke? The lighter patches below the waterline are sediments (primarily sand) that cover the bedrock. The canoe is ~4.5 meter in length.

Even below the waterline, shadows are cast from the submerged rocks as it was a sunny day and the water was clear. Many of the shadows delineate the trace of bedrock fractures — Sam is using these images to quantify the orientation of lineaments at a detailed scale that’s not possible without the drone imagery.

It was a long day of both flying and floating, but we got a set of spectacular images that will advance Sam’s research, and we’ve got ideas about future research using this modern technology. Research for the Bold!

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.

COOL