Light at the End of the Tunnel: Geological Research at Crozet’s Blue Ridge Tunnel

By Katie Lang ’18

A new trail has opened in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains — in late November, after years of work, Nelson County opened the Blue Ridge Tunnel, a mid-19th century railroad tunnel as a trail for the public to enjoy. Before this rail trail opened to the public, the William & Mary Structural Geology & Tectonics Research Group had the opportunity to investigate the geology inside the tunnel. It was the focus of my undergraduate Honors thesis research in 2017-18, entitled: Kinematics of brittle and ductile deformation in the Catoctin Formation near Rockfish Gap, Virginia. I also presented these results at a Geological Society of America conference in the spring of 2018.

After graduation, I moved west to Western Washington University, and I’m now finishing my Masters’ degree in structural geology on the geochronology of an ancient subduction zone in the north Cascades. As the Blue Ridge Tunnel is now open to the public, it’s a great time to highlight the findings of our research and shed light on Virginia’s rich geological heritage.

By 2017, the tunnel restoration process had begun and in partnership with the Claudius Crozet Blue Ridge Foundation, we obtained access to the tunnel – commencing a project to map and understand the geology inside the Blue Ridge Mountains. It was a unique opportunity because, for better-or-worse, geologists are generally left to stumble around on the Earth’s surface looking for exposed bedrock, going deeper requires subsurface drilling which is typically expensive.

Claudius Crozet, circa 1855, sporting some crazy two-tone mutton chops (from the Virginia Military Institute Archives).

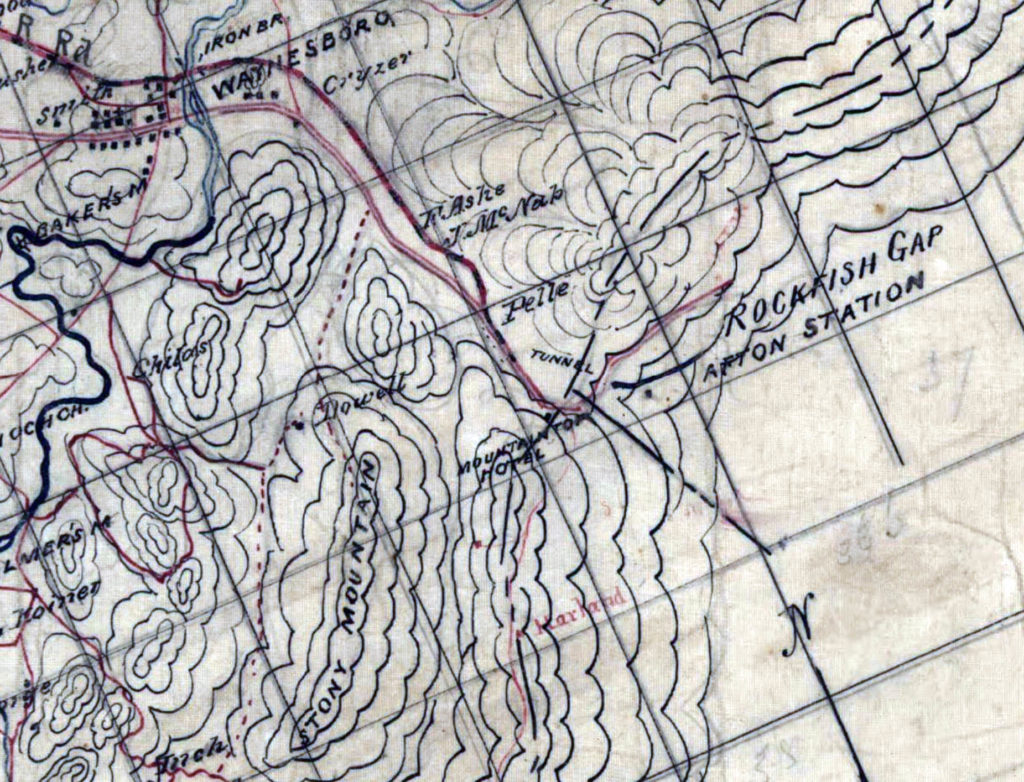

But first, some recent history by geology standards. In the early to mid-19th century, as America’s burgeoning railroad industry grew, the Blue Ridge Tunnel was conceived and later engineered by Claudius Crozet, as a way to connect eastern Virginia with western Virginia and the Ohio River Valley. The Blue Ridge Mountains formed a significant barrier for both people and goods to get to the western reaches of the state. Rockfish Gap, the lowest elevation along the crest of the Blue Ridge for more than 120 miles, provided the optimal location for a rail crossing. It’s still the easiest path across the mountains, as today’s Interstate 64 crests the Blue Ridge at Rockfish Gap (pdf) (NOT at Afton Mountain, a common misperception).

In 1850, construction of Crozet’s tunnel began from both sides of the Blue Ridge. Boring a tunnel through the Blue Ridge was particularly treacherous as workers only had black powder and hand tools at their disposal to cut into the rock – evidence of that human labor is still tangible, preserved in the drill holes visible throughout tunnel. In 1858, the 4,237′ long tunnel beneath the Blue Ridge was completed, five years behind schedule.

Inset from an 1862 topographic map by Jedediah Hotchkiss illustrating Rockfish Gap and the tunnel beneath the Blue Ridge. Map covers ~3 x 2 miles.

During World War II, the original Blue Ridge Tunnel was replaced by a new (and adjacent) tunnel designed to accommodate the bigger trains that the war demanded. In the mid-1950s, plans were made to store natural gas in Crozet’s out-of-use Blue Ridge Tunnel, and two concrete bulkheads were installed to create storage space in the center of the tunnel. Natural gas was never stored in the tunnel, but the concrete bulkheads partitioned off the interior of tunnel. The central section of the tunnel was accessible only through 20’-long metal pipes that transected the huge concrete wafers. With the bulkheads in place there was no light at the end of the tunnel – just darkness 🙁

William & Mary geologists contemplating the concrete bulkhead inside the Blue Ridge Tunnel in 2017 (photo by Pablo Yañez).

The goal of my research was to characterize the geology of the Catoctin Formation (pdf), a sequence of lava flows that erupted 550 to 575 million years ago. Over time, rocks can undergo metamorphism and deformation, which are fancy geology terms for saying that the rock got hot enough and was buried deeply enough to transform the original volcanic rock into a new metamorphic rock, a metabasalt, more commonly known as greenstone. I was particularly interested in the geological structures that resulted from this change, namely that of foliation, fractures, and other strain indicators that formed under the stresses that the Catoctin Formation endured millions of years ago as ancient tectonic plates collided.

Rocks of the Catoctin Formation, in the Virginia Blue Ridge. Left- greenstone, Right- meta-sandstone, note the steeply inclined bedding.

Mapping the tunnel’s deep interior was exciting, as the old William & Mary tag line goes, our was research ‘For the Bold’! At the concrete bulkheads, we’d wade into ponded water on the floor of the tunnel and then wriggle through the damp, rusting 2’-diameter pipe, ultimately emerging into more ponded water and total darkness on the far side of the bulkhead.

Images of the bulkhead and pipe to access the deep interior of the Blue Ridge Tunnel (circa 2017). Left- Pondering whether we really want to crawl through this pipe, Right- Inside the pipe, note water at the base of the pipe.

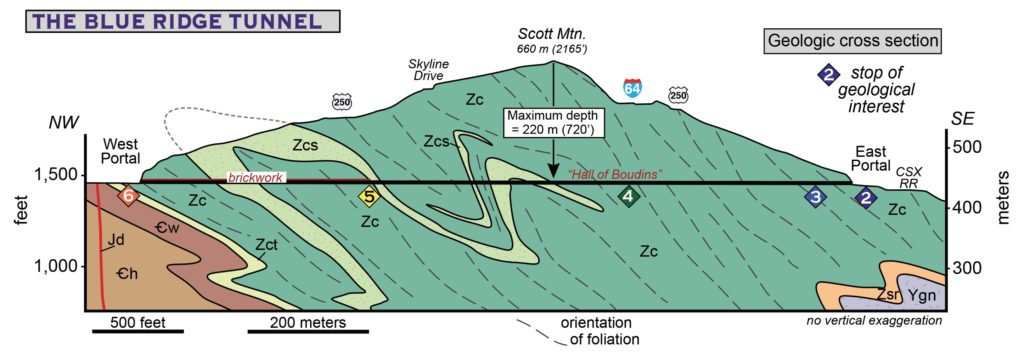

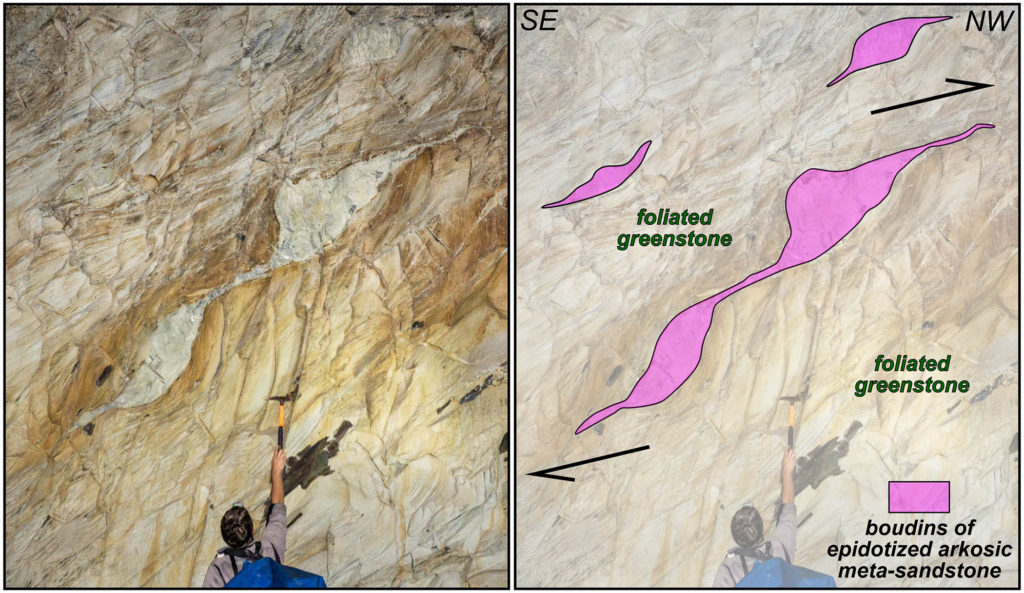

However, the deep recesses of the tunnel revealed some of its wonderful secrets – it was here we discovered the “Hall of Boudins.” Boudins (French for sausage, and sometimes bread loaves of a similar shape) occur in deformed rocks when there are multiple layers with different mechanical properties. Often, the resulting sections of rock layers look like chains of sausage or other shapes that vary in width and geometry. During our mapping, we noticed distinctive and abundant asymmetric boudins in the central part of the tunnel. These are complex boudins and they remain my favorite scientific find of the project, since the shapes are so unique and can tell a geologist much about how the rocks were transformed during deformation. The asymmetric nature of the boudins indicates that tectonic forces sheared the rocks in the Catoctin Formation, transporting them many miles to the northwest of their original location.

There is now light at the end of the Blue Ridge Tunnel as both concrete bulkheads have been removed and the trail is open.

We’ve got materials to help everyone learn about the geology both inside and outside of the tunnel. Check out our geological field guide to the Blue Ridge Tunnel (pdf)! It’s meant to be used in the field- so print it or view it on your favorite mobile device. Places like the Blue Ridge Tunnel are special as they provide the perfect nexus between science, history, and outdoor recreation.

Geologic cross section through the Blue Ridge Tunnel, Virginia. Note the stops of interest that can now be easily be visited in the tunnel.

Check back later, as in early 2021 we’ll be filming videos and creating more digital content about the geology of the Blue Ridge Tunnel.

A few final pictures below.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.

I am a retired teacher of Earth Science from a Lynchburg, VA and was thrilled to explore the newly opened tunnel this week. Yes, I observed and photoed the structures you identified as Boudins and am very pleased to find your post. Great job Tribe!

This was a great read, Katie! I’m glad you were able to put the field guide together about this location. I remember it from the 2017 field conference! Can’t wait to see more this year.

Toured the tunnel today! Thanks for your insights which enhanced my visit.