Summer Research: It’s About Time

Mid-summer is here, and it’s been a busy few weeks for my undergraduate research students. The 2018-19 William & Mary Structural Geology & Tectonics Research Group is focused on an array of projects with study sites from Europa (the satellite) to Oman and Virginia. This year we’re working to better understand when significant tectonic events occurred, as well as determine the rates at which these processes took place.

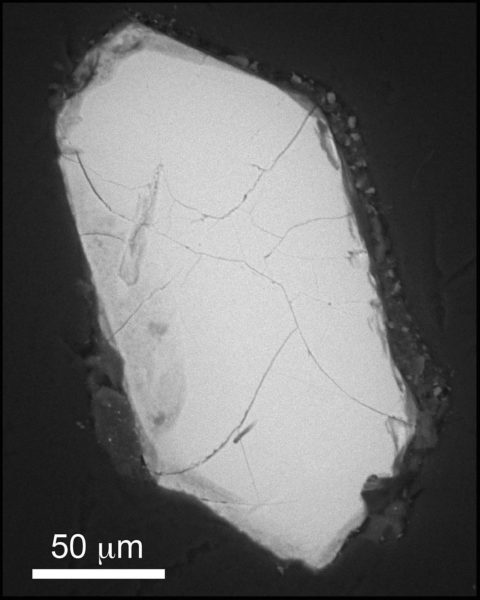

Scanning electron microscope image of a zircon grain from felsic volcanic rock exposed as a clast at the Puddledock quarry near Hopewell, Virginia. Image taken at the UCLA SIMS lab.

Geochronology is the science of quantitatively determining the age of earth materials, and it is a key component of modern earth science. We’re collaborating with geoscientists at the University of Texas-Austin, the U. S. Geological Survey, and the University of California Los Angeles on these projects. We’re undertaking Ar/Ar dating on K-bearing minerals, U/Pb dating on zircon and titanite, U/Pb dating of detrital zircons, and U-Th/ (He) dating on apatite. That’s an alphabet soup of radioactive elements whose decay happens at a known rate providing a chronometer for the Earth’s history.

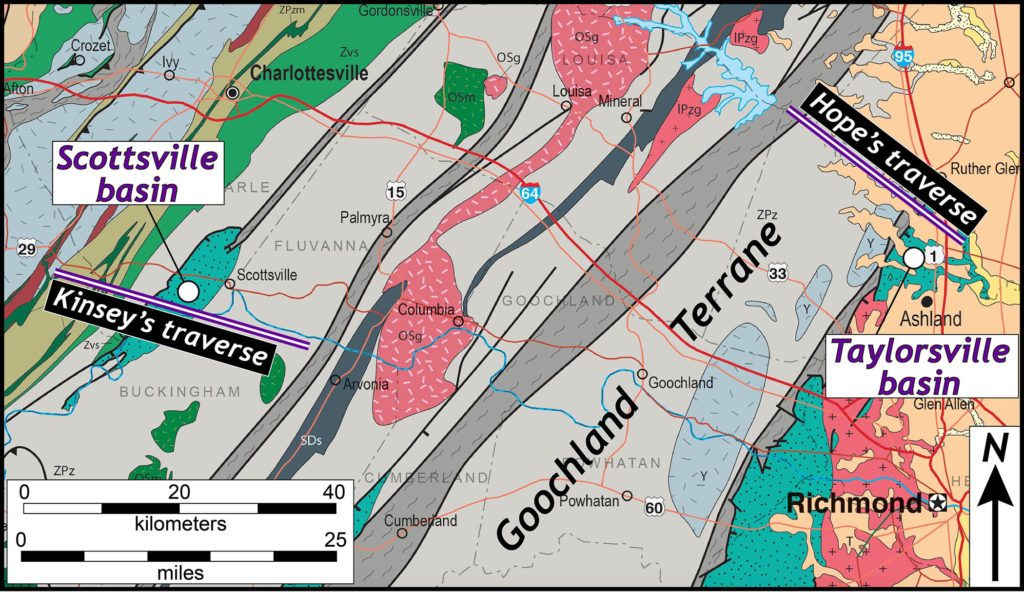

Study sites and traverses in central Virginia. Modified from the Geologic Map of Virginia (Bailey et al., 2018).

Hope Duke’s senior thesis is focused on the Goochland Terrane in the eastern Piedmont. This suite of enigmatic rocks was metamorphosed at high pressures and temperatures during the Paleozoic collision that created the Appalachians, and then the rocks were exhumed to the surface in the Early Mesozoic (as evidenced by clasts of Goochland Terrane rocks in the Triassic Taylorsville basin). Yet the timing details for what happened and when in the Goochland Terrane are sketchy. Hope’s going to date a suite of minerals (each with a different closure temperature) along a traverse across the Goochland Terrane into the Taylorsville basin. These ages will provide constraints on when the terrane was deformed and the rate at which the rocks cooled as they were exhumed. Ultimately, this study aims to determine whether Appalachian Mountains collapsed under their own weight or were brought low by tectonic rifting that birthed the Atlantic Ocean.

Hope’s collected rocks from outcrops along the North Anna River, and many of her samples have been hard-won involving long traverses through the puckerbrush* to reach bedrock exposures.

Hope Duke (at the back) and members of the W&M Structural Geology & Tectonics Research Group examining an outcrop in the puckerbrush along the North Anna River, Virginia.

Kinsey Wilk’s senior research project is centered on the Scottsville basin, a small Mesozoic rift basin in the western Piedmont. The basin is a classic half-graben bound by a normal fault to the northwest and an unconformity on its southeastern margin. During the formation of a half graben, rocks in the footwall are exhumed (and cooled), whereas the rocks in the hanging wall are down dropped and buried – this produces different thermal histories on either side of the basin. By dating a suite of minerals with relatively low closure temperatures Kinsey will determine the timing of basin formation and rate of fault movement.

Kinsey’s samples come from a traverse across the footwall block, the basin, and into hanging wall. Rather than battle with the Piedmont puckerbrush, we used canoes to float down the James River and across the basin – collecting samples from the outcrops in the river. Easy peasy!

William & Mary geologists Kinsey Wilk and George Denny on the James River at a outcrop of arkosic conglomerate in the Scottsville basin.

We’re being guided in these endeavors by my former research student Zach Foster-Baril, a current Ph.D. candidate at UT-Austin, who is conducting a more extensive study of eastern North American rift basins.

George Denny’s study site is not as accessible as the rocks exposed in the Virginia Piedmont because his study site is ~700 million kilometers away on Jupiter’s icy moon Europa. He is testing kinematic models for crustal deformation on Europa. But George, a geology and physics double major, does not want to spend all summer in the lab staring at a computer so we designed a geophysical survey as a side project. He is the lead on a magnetic survey that we conducted in conjunction with the Polycor Corporation at one of their quarry sites in central Virginia. This is a collaborative project that provides hands-on applied research for W&M students and will benefit Polycor in assessing their geological resources.

W&M geologist George Denny with a portable magnetometer at a dimension stone quarry in central Virginia.

When my research students aren’t in the field they’re on campus – in the lab characterizing their samples, separating minerals, plotting their structural data, and creating digital maps and cross sections. Later this summer, Hope and Kinsey will travel to Austin and Reston to conduct their geochronological analyses. Busy and exciting times, but that’s how the W&M Structural Geology & Tectonics Research Group rolls.

*puckerbrush is a colloquial term used to describe any vegetation, most commonly understory vegetation, that makes passage through the forest difficult, unpleasant, or hazardous.

No comments.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.