Searching for Hylas

We are deep into the spring semester and my teaching/administrative duties are gobbling up most of my weekdays and nights. There is hardly a moment for research during the week, so research gets done on the weekends. I spent this past Saturday in the field searching for Hylas, the Hylas Fault Zone that is, not Hylas of Greek mythology. As the story goes, the mythological Hylas journeyed with the Argonauts, but while on an errand to fetch water he was abducted by nymphs. His mates searched in vain and Hylas was left to his fate. In 1976, Andy Bobyarchick described a zone of both ductile and brittle fault rocks near the small crossroads of Hylas, Virginia (~25 km northwest of Richmond) and the Hylas Fault Zone entered the geological literature.

Jump forward three and a half decades and John Hollis, a W&M geology major, has commenced his thesis research on understanding the brittle deformation history of the Hylas Fault Zone. During the past six months, John sought out exposures of bedrock in stream valleys and quarries to understand the structural geology of these rocks. On Saturday we put a canoe into the North Anna River: a floating traverse across the eastern Piedmont in search of the Hylas Fault Zone.

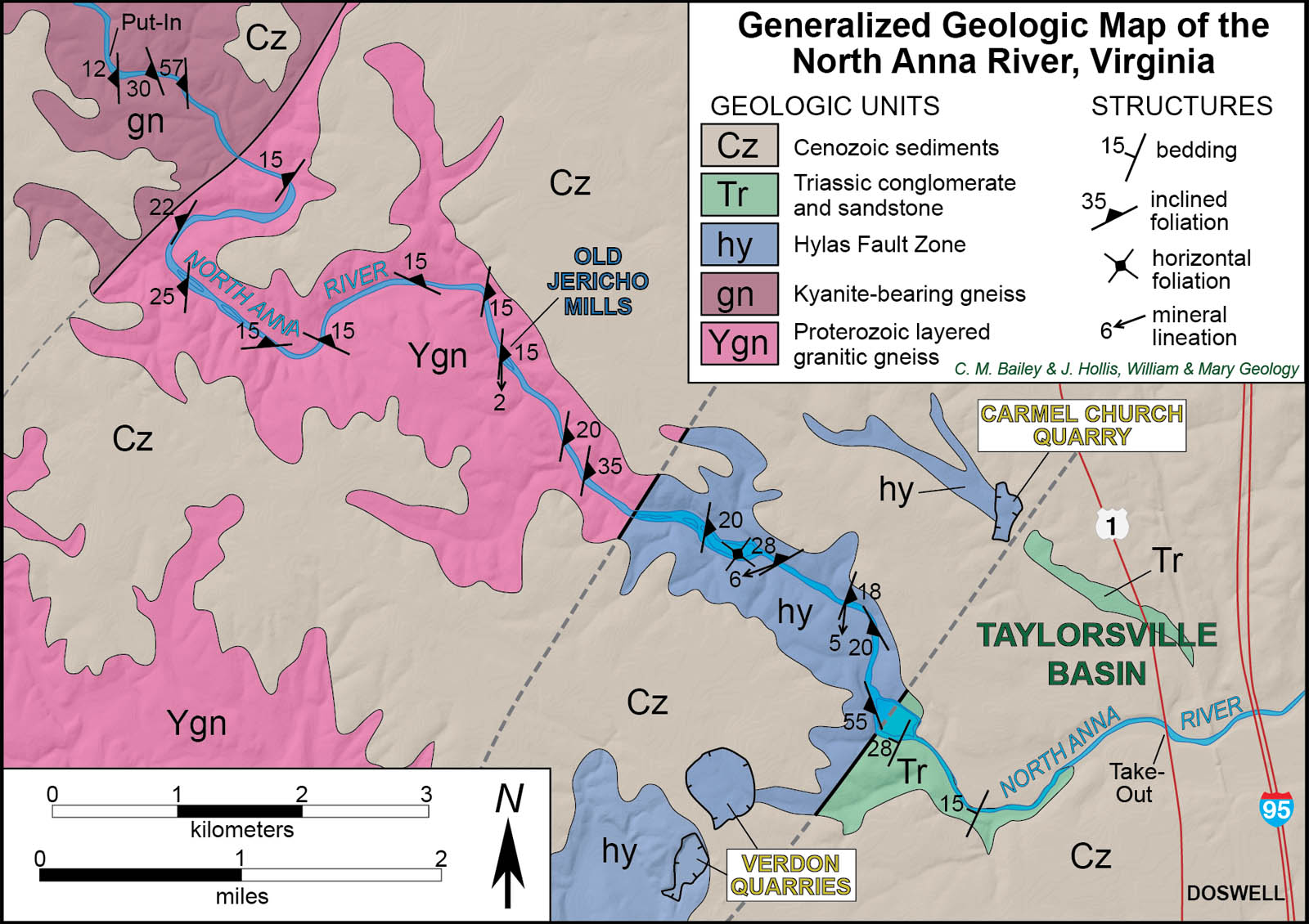

Generalized geologic map of the North Anna River region. Structure data from our canoe trip, geologic contacts from our data and other sources.

For February, the weather could not have been better (although a bit on the chilly side for nymphs). The North Anna was similarly cooperative, flowing at a comfortable rate that easily floated the boat, but left most of the bedrock outcrops above the waterline. We glided by a veritable menagerie of metamorphic rocks in the enigmatic Goochland Terrane, examining thinly layered gneisses, coarsely banded gneisses, pegmatitic gneisses, biotite-garnet schists, and amphibolites. We measured the orientation of ductile and brittle structures in these impressive channel and riverside cliff outcrops.

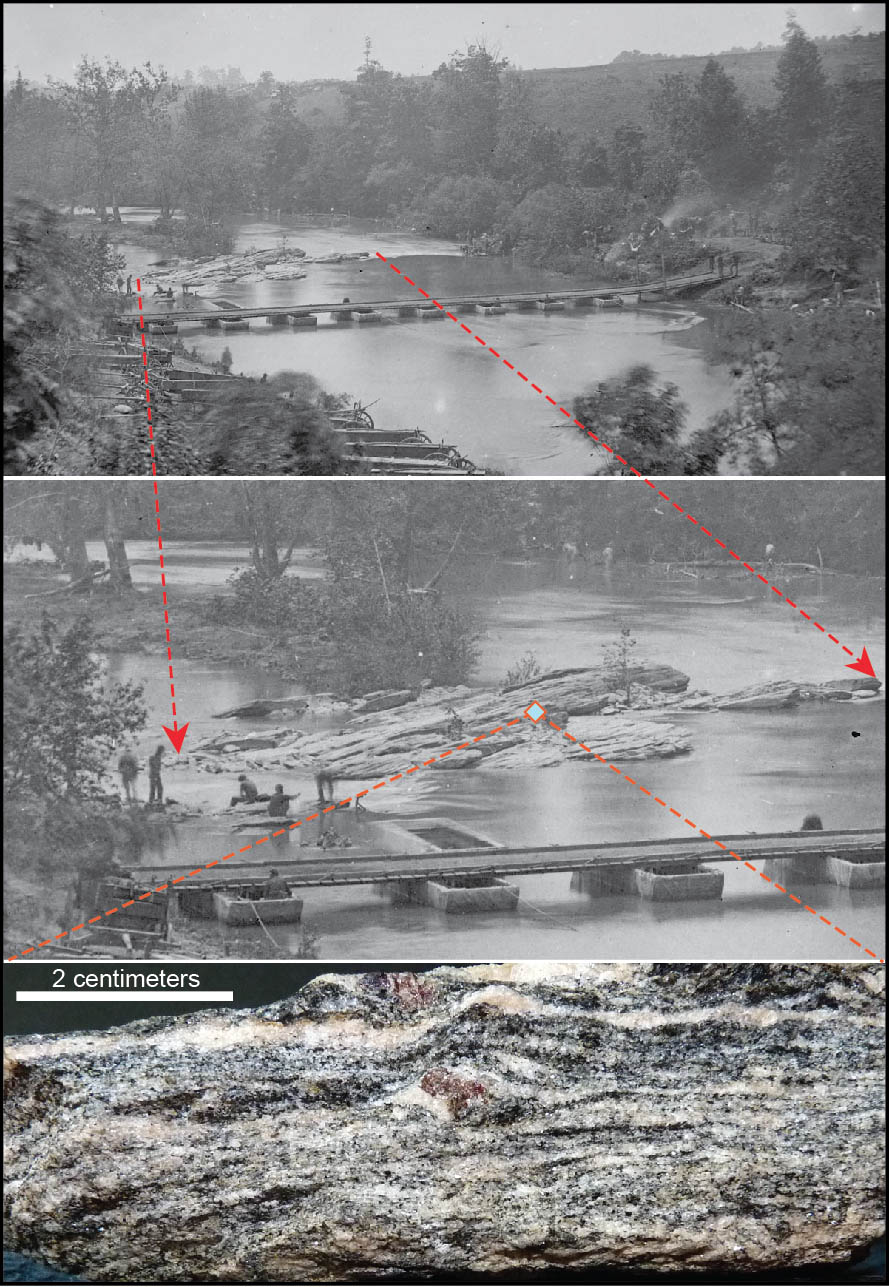

Halfway into the trip we lunched at a large low outcrop of biotite-garnet gneiss cut by two generations of brittle fractures. Immediately northeast of the river stood the stone foundations and derelict chimney of Jericho Mills. In May 1864, Jericho Mills formed a major crossing point for the Union Army as it pressed south against the Confederate Army. A photo dated May 24th 1864 by Timothy O’Sullivan shows a pontoon bridge spanning the North Anna just upstream from the mill and the same outcrop upon which we lunched, measured structures, and collected a sample 148 years later. For me, this nexus of human history, geologic history, and now my personal experience defies easy description but is somwehere between surreal and cool. O’Sullivan’s photos illustrate that the terrain bordering the North Anna was mostly open country during the Civil War: today that same terrain is cloaked in forest and the vestiges of past human activities are greatly muted. On this tranquil float, it was difficult to conceive that we transited a battleground on which more than 5,000 Americans were either killed or wounded during those four days of fighting long ago.

Top-1864 photo of the North Anna River at Jericho Mills. View to south-southeast. Middle- close up of bedrock outcrop in river, note pontoon bridge, Union soldiers in the river, and gently dipping foliation. Bottom- sample of biotite-garnet bearing gneiss that we collected on February 18th, 2012 from the mid-river outcrop.

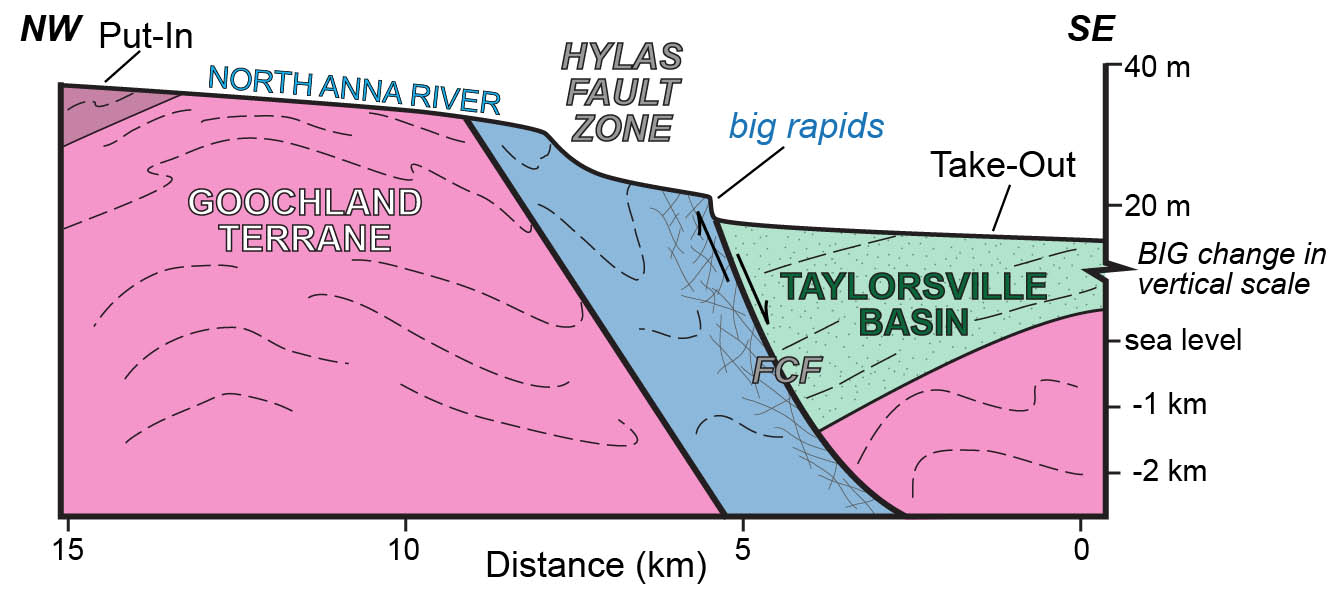

The North Anna flows with a subdued gradient across the Piedmont, but in the last few kilometers before arriving at the Coastal Plain the river drops through a sequence of rapids that define the Fall Zone. These rapids got our attention as we coursed quickly past the bedrock in whitewater. After negotiating the big Fall Zone rapid we caught our breath on the broken rocks on the east side of the Hylas Fault Zone. These rocks have enjoyed more deformation than most: when these rocks were hot, but not molten, they were sheared and squeezed. Later these rocks were fractured, faulted, and mineralized. A suite of narrow jagged veins angle through the rock, these veins look suspiciously like pseudotachylite. Pseudo what? Pseudotachylite is a dark glassy fault rock formed by frictional heating, melting, and subsequent quenching. These veins may record paleoearthquakes in the Hylas Fault Zone.

Top- W&M senior John Hollis surveys the rapids along the North Anna River and the fault rocks under foot. Bottom left- fractured mylonitic rocks from the Hylas Fault Zone. Bottom right- pseudotachylite veins (P) cutting mylonitic gneiss.

Just below the rapids, we quietly glided over the Fork Church Fault, the eastern boundary to the Hylas Fault Zone. Although we never saw the Fork Church Fault, it is a whopper of a normal fault with thousands of meters of slip and it forms the boundary fault to the Taylorsville Mesozoic basin. We were delighted by the mossy outcrop of boulder conglomerate that signaled our arrival in the Triassic rift basin. The character of the North Anna changed dramatically as well: the Fall Zone rapids were behind us, bedrock outcrops became sparse, and the river birches formed a nearly unbroken canopy above the river. Another research adventure complete, we pulled the canoe off the water in growing twilight.

North Anna River profile, note rapids in the Hylas Fault Zone and low gradient across the Taylorsville Mesozoic basin. Schematic of the subsurface geology. Both river profile and geology section are vertically exaggerated. FCF- Fork Church Fault.

We learned much from our float trip. John has a heap of new data to chew on and incorporate into his thesis. Some of our observations don’t jive with previous studies and we’ve got a host of new questions about the regional geology. Geologists are fortunate in that the field is commonly where we go to collect our primary data. Although time consuming, fieldwork is often sublime and beautiful.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.

This was a pleasure to read this article. Very interesting 1864 photos. Alas, the irony, my son John (the one in the photo) has gotten married and moved on from his family of origin. We are proud. One might think he could become our “Hylas” son. But we think not, as we hope to see and Carrie often.

Really liked what you had to say in your post, W&M Blogs » Searching for Hylas, thanks for the good read!

— Theola