Resurrecting the Reef: Undergrad’s research goes global

Kharis Schrage, a junior here at William & Mary, works in the the Allen Lab where she studies delicate marine invertebrates called hemichordates (a small, unusual phylum of worm-like creatures). Little did she know that her W&M research experience would one day have her flying halfway across the world on her own to lead a research project in Australia. Before finals began last semester, she was boarding a plane to head to a research lab located on the northern part of the Great Barrier Reef where she had the opportunity to work with international colleagues of Dr. Jon Allen to help find out exactly how one species of sea star has been responsible for 40% of the destruction of the Great Barrier Reef.

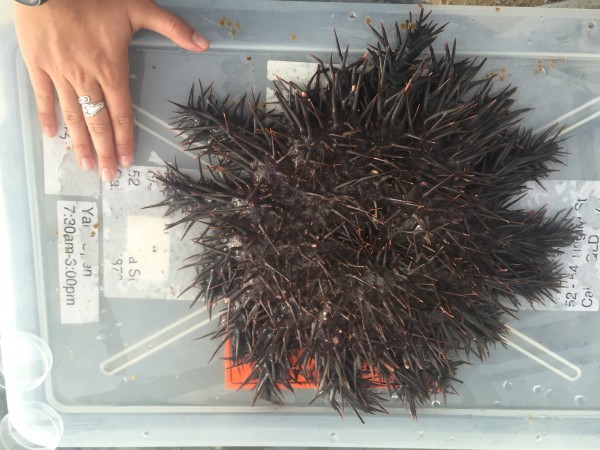

Crown of thorns are a species of sea star, native to the Great Barrier Reef, that can grow to nearly a meter in diameter (that is the same size as your average umbrella). They feed on coral and typically follow a “boom-bust” cycle of reproduction in which large population increases or “booms” are followed by periods of population die-offs or “busts.” Recently outbreaks have been reported with increasing frequency, potentially killing off coral faster than it can recover. It was thought for decades that more crown of thorns were surviving because their predators, including helmet snails and conchs, had been depleted by humans hunting them for their shells. Researchers have tried multiple strategies to control the crown of thorns populations, from attempting to restore their predators to even using robots to target and kill crown of thorns. However, all of these attempts have failed to control the population, leaving researchers puzzled as to why exactly this cycle of outbreaks is happening and scratching their heads about what to do.

The population growth of crown of thorns is much more complex than how many eggs each sea star can lay (which, by the way, is typically around 60 million eggs per sea star). Under stressful environmental conditions, sea star larvae have the ability to clone themselves. When other species of juvenile and adult sea stars experience stressful environmental conditions, they are able to drop one of their limbs which can be regenerated and, in some species, the dropped arm can subsequently grow into a whole new organism. As a result of the regenerative ability of sea star adults and their larvae, Dr. Allen and his colleagues asked the question, “are these eternal larvae?”

“We could be grossly underestimating the productive abilities of a single adult”

To investigate which environmental stressors could be responsible for the increased population booms, Kharis and her Australian colleagues looked at how larvae developed in different levels of salinity, pH, temperature, and nutrients. In the lab, Kharis and her team monitored the growth of embryos and hatching under these different conditions to see which conditions were most stressful to their development. Though they found that lower salinity delayed hatching, the true driver of these population booms is nutrient runoff. Low salinity is often tied to nutrient runoff, but the increased food stimulated by the additional nutrients allow more of the larvae produced to survive.

So how do we stop the the crown of thorns from completely wiping out our coral reefs? Simply stated, “Stop dropping a bunch of nutrients in the ocean. It’s a bad idea.” The Great Barrier Reef is threatened tropical storms, global warming, and crown of thorns. As we cannot control the weather and climate change cannot be controlled on a local scale, the best bet is to limit the amount of nutrients that are entering waterways and making their way to the ocean. It is within our control to limit the amount of food reaching these larvae; hopefully, altering their reproductive cycle to one that allows the corals to recover.

As for the experience itself, Kharis said that it was something that she never thought she would be doing as an undergrad. “Within 20 minutes of landing on the island, I was working in the lab,” says Kharis. Not only was she conducting her own research, but she was coordinating the lab and teaching her colleagues about the biology of these organisms. “It was really cool to be thrown into this situation in which I was in charge of this project and was telling professors and postdocs what to do. It was a very unique experience.” In addition to the lab work and getting to go snorkeling every day, Kharis did have to finish her finals while in Australia. Granted, she got to study on a tropical beach instead of in Swem Library.

Has this story piqued your interest in getting involved in research? Both Dr. Allen and Kharis recommend finding something that you are really passionate about and getting involved early on in your college career. Kharis started working in Dr. Allen’s lab after being selected as one of the recipients of an HHMI Freshman Research Grant, but there are other ways to go about it if you aren’t so lucky. You can reach out to specific professors about their research, but don’t do so ignorantly.

“Students who approach professors and have a reason to approach them in particular are more likely to get into the lab, like if you’ve read up on them and have a broad understanding of what they do…Take an hour to look over their website, read a couple of their recent papers, and craft an email to them that shows that you did that.”

As for what to expect once you are in a lab, your experience will really vary based on who’s lab you’re in and the kind of work you will be doing. “Basically, I count worm poop,” says Kharis. Science isn’t always glamorous and can often seem tedious and mundane. Kharis says there are weeks where she will spend most of her hours out in the field, and others where she’ll be running experiments in the lab and entering data. It is for that reason that you should be truly interested and excited in the work that you are doing. Research is a huge time commitment and requires a good work ethic and time management skills. Conducting research is not about having a resume builder, it is about learning how to contribute to the scientific community in a meaningful way. “If you are willing to work hard and are interested and happy to be in the lab, then you will be rewarded,” says Dr. Allen. The most important aspect of any research lab, however, is finding a collaborative environment in which everyone has a shared excitement for the work being done. Kharis’ experience in Dr. Allen’s research lab has not only provided her with the tools necessary to make it in the field of science, but has taken her around the world and given her experiences that she may have otherwise never had. And for that, she wouldn’t give up counting worm poop for anything.

Want to get involved?

- Learn more about undergraduate research at W&M and VIMS

- Find out more about the National Science Foundation’s Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) summer programs

- Learn more about research being done on the Great Barrier Reef

- Check out more work being done by the Allen Lab

No comments.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.