Traipsing across the Piedmont: A Day Trip thru Geology and History

The W&M Geology Departmental Spring field trip left the Atlantic Coastal Plain last Sunday morning for a quick dash westward into the Piedmont: a day trip with equal measures of geology and history in the mix. As is our tradition, W&M undergraduates conducting research in a particular area lead the trip which is open to all comers.

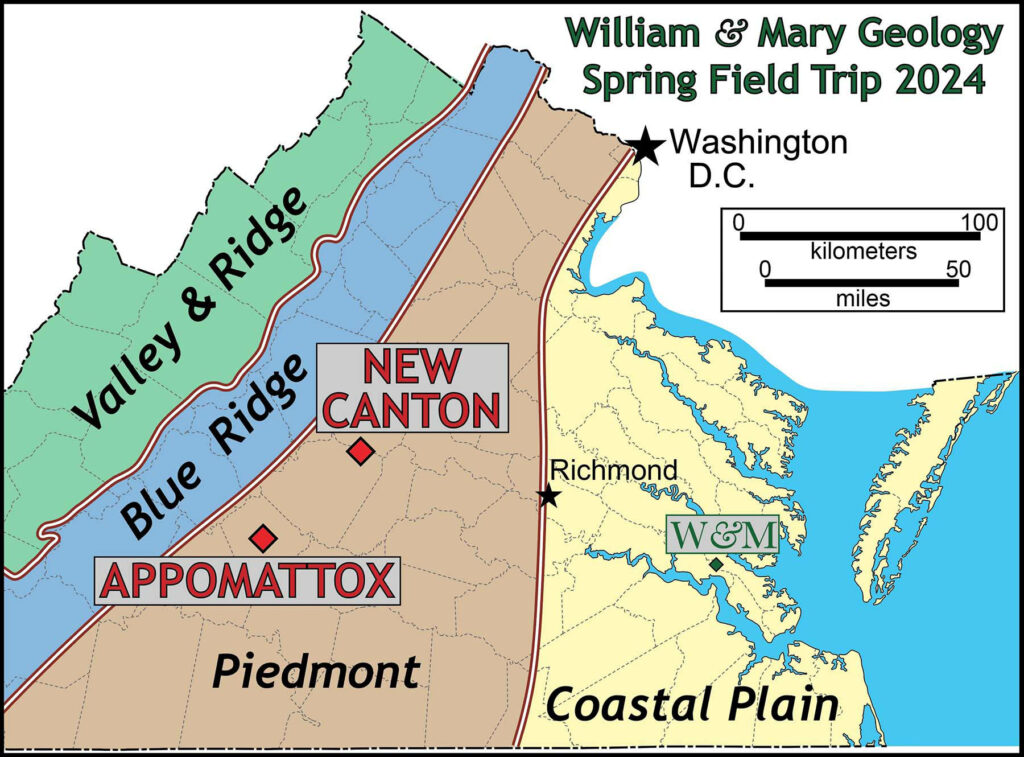

Map illustrating the location of field trip stops in the Piedmont at New Canton and Appomattox, Virginia on the Spring 2024 William & Mary Geology departmental field trip.

In the early morning chill, we departed Williamsburg. But by the time we arrived at our first stop ample sunshine was serving up higher temperatures with a pleasant late winter day in the offing.

Our stop was at New Canton, a village in northeastern Buckingham County on the south side of the James River. Along the bluffs, just north of ‘town’, are exceptional outcrops that offer insight into Virginia’s turbulent tectonics from days of old.

Annika Wolle ’25 showed off the outcrops to the assembled masses. Her research is focused on working out the depositional age of the Arvonia and Buffards formations, a long-studied, but enigmatic suite of meta-sedimentary rocks. It’s one of the only fossiliferous units in the Virginia Piedmont, and as such has attracted paleontological attention since the 1890s. The long-held consensus is that these rocks were deposited in the late Ordovician (~445 million years ago) on the heels of the Taconian orogeny, but our recent work indicates that these rocks are considerably younger.

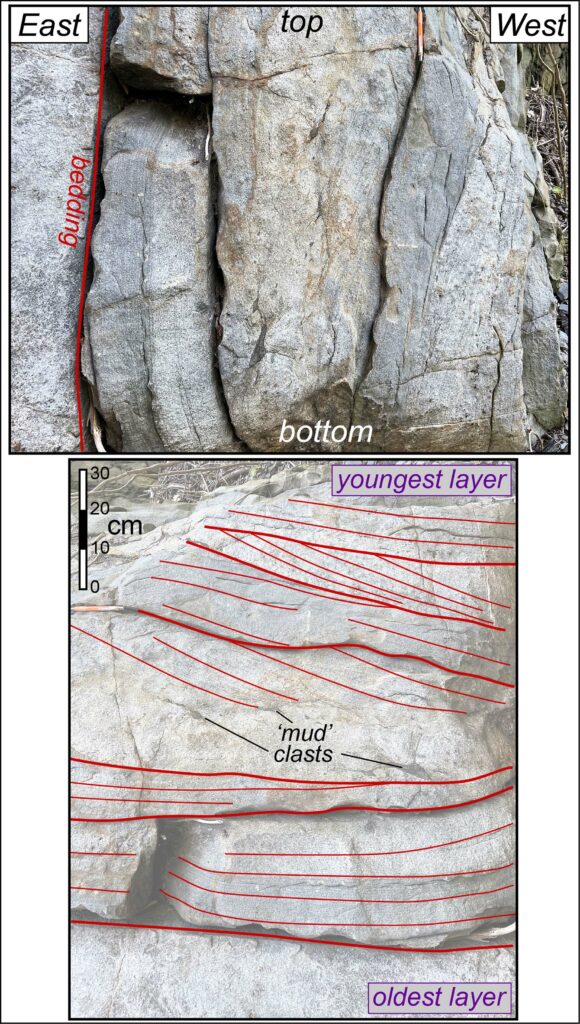

Annika walked her peers through a sequence of outcrops exposing ‘knotted schist’, schistose quartzite, quartzite, and meta-conglomerate – these were once sediments, mud, sand, and gravel deposited in a successor basin. Today these rocks are well-foliated and turned on their side such that the original layering is nearly vertical. What’s cool is that primary structures such as cross stratification are still evident in these metamorphosed rocks.

Top – Vertical layers of cross bedded quartzite at New Canton. Bottom – Same image rotated 90˚ such that bedding is subhorizontal- note the cross beds and ‘mud’ clasts.

We finished our visit to New Canton, by estimating the current discharge of the James River. A river’s discharge (Q) is given by multiplying the cross-sectional area of the channel (A) with the average velocity of flow (V). Our technique for estimating the flow velocity was rather old school, as we chucked a few old withering apples into mid-channel and then timed the bobbing apples as they moved with the current. You’ll be delighted to know that at midday on February 25th the James River at New Canton, Virginia was discharging about 130 m3 /sec, a tad below the seasonal average for late February.

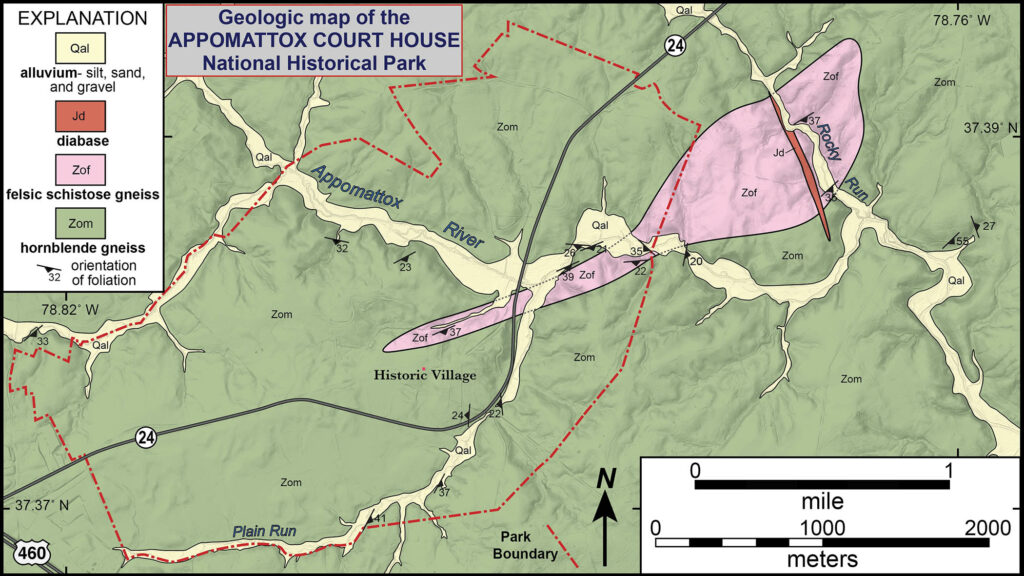

From New Canton we ventured further into the Piedmont arriving at Appomattox Court House National Historical Park for a picnic lunch. As part of Nailah Johnson’s senior research she’s mapped the bedrock geology in and around the park.

Simplified geologic map of the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, mapping by Nailah Johnson and others.

We started our adventure in the restored historic village, Nailah noted it was here, back in April 1865, that Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses S. Grant’s Federal forces effectively ending the American Civil War. But Nailah was straight forward and clear minded – she was not going to spend time talking about two long dead white guys.

Rather, Nailah wove together a powerful narrative about freed African-Americans who lived at Appomattox Court House and the struggles that these marginalized people faced both during and after the Civil War. It was an epic history lesson.

In the afternoon, we hiked across this gentle and rolling terrain. In this part of the Piedmont, outcrops of bedrock are few and far between – it’s a realm where chemical weathering has taken its toll, altering the bedrock into saprolite and a thick soil. However, we did find rock in an unusual location – the foundation and chimney stone at Sweeney’s Prizery.

W&M geologists at Sweeney’s Prizery at Appomattox Court House National Historical Park discussing the foundation and chimney stone in the late 18th century structure. The metal siding and gutters are more recent additions to the building.

What’s a prizery? Well, it’s a structure where tobacco was stored and packed into hogsheads (large barrels) in a process called prizing, the hogsheads were then shipped to market. Sweeney’s Prizery dates back to the 1790s and is likely the oldest structure in the park. The prizery’s foundation and chimneys include an array of stone blocks, some of which are more than a meter in their long dimension. These rocks were locally quarried, just a few hundred meters away, from modest natural exposures along the Appomattox River. We wondered about just whose hands had quarried and set these blocks in the stone wall.

At Sweeney’s Prizery there are two distinctive rock types – a light-pinkish gray feldspathic gneiss and dark grayish black hornblende gneiss. Nailah’s research indicates these rocks were once igneous rocks, most likely rhyolites and basalts. Nailah’s employed isotopic analysis of zircons in the feldspathic gneiss to determine that the rhyolitic protolith crystallized 540 to 570 million years ago, at the end of the Ediacaran Period when continental rifting was tearing the old supercontinent of Rodinia apart. Much later, during the tectonic train wreck that created the Appalachians these rocks were transformed into strongly deformed metamorphic rocks.

W&M geologists enjoying the late winter sunshine at an outcrop of feldspathic gneiss along the Appomattox River.

It was a great day for the W&M Geology community – a delightful time to get away from campus and explore the Earth. The field trip season is just starting for us, as over the next two months many Geology classes will be venturing forth from campus to study and collect data in the field.

Great blog post Chuck! I was so glad I could be a co-leader for this department field trip! I’d never thought I’d ever do this in the Geology department and I’m glad that I did!

Hopefully everyone learned that Appomattox doesn’t have any lineated quartzites since it’s all meta-igneous rocks. LOL!

Thank you for this geological and historical journey. It’s just as I remember it. We had a splendid time. Cudos to Nailah and Annika.

It was super cool getting to see some of my peers research in the field, as well as learn some of the history of the area that isn’t as well known! Trips like this have always been one of my favorite ways to learn geology as you can’t beat the hands on experience.