Rolling Deep with the Penrose Conference on Orogenic Systems

This past week I co-convened a Geological Society of America Penrose Conference focused on Feedbacks and Linkages in Orogenic Systems. An orogen is a geologic term for a mountain belt, and orogenesis describes the processes at work in mountain belts (derived from Greek- oros for “mountain” and genesis for “creation/origin”). The world’s great mountain belts include massive modern ranges such as the Himalayas, Andes, and Alps as well as ancient mountain belts such as the Caledonian orogen in Greenland, Scotland, and Scandinavia, the Grenvillian orogen in Canada, and the Limpopo orogen in South Africa.

The Penrose Conference included structural geologists, petrologists, sedimentologists, geomorphologists, geochronologists, and geophysicists all with a common interest in orogenic processes. Geoscientists from as far away as China and Poland traveled to Asheville, North Carolina for nearly a week’s worth of discussions, talks, posters, and field trips. Penrose Conferences are small meetings where the participants are encouraged to present novel or controversial hypotheses and hash out those ideas with colleagues.

Penrose Conferences were first established in 1969 and over the last 45 years these meeting have helped bring forward many major advances in the realm of plate tectonics, ophiolites, and metamorphic core complexes (to name just a few topics). For me it was a great pleasure to co-convene a Penrose conference, I reconnected with old colleagues and met many new ones. The National Science Foundation paid the freight that enabled participation by a large contingent of graduate students, the interaction between established scientists and up-and-coming scientists was special.

The Conference honored Bob Hatcher, who first brought a plate tectonic focus to the Appalachians back in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Today working with his large and eager group of graduate students (aka the Hatchery), Bob continues to make seminal contributions to the field.

We experienced the fickle nature of the southern Appalachian spring on our field excursions. The first trip started under heavy overcast with a malignant wind and wet snow blanketing the outcrops. By the last stop on the final field trip day we were broiling in Carolina sunshine.

Views from the field trip: left- snowbound in the Blue Ridge Mountains at the 2nd stop, right- broiling in the Brevard Fault Zone at the last stop.

That evening as our crew of sun-drenched and thirsty geologists pulled to the curb in downtown Asheville and headed straight towards a brewpub, a natty hipster on a skateboard took one look at the group and commented, “Ah, you’re rolling deep.”

Rolling deep? Some of the brightest geologic minds I know were utterly stumped as to just what it meant to be rolling deep. I’ll use the phrase in a sentence:

“Me and my Penrose posse were rolling deep in the Brevard Fault Zone looking for trouble and some dextral transpression.”

The geologic lexicon is rich with colorful expressions (for instance- there are glacial erratics, faults have both throw and heave, and ocean lithosphere can be obducted). I have no doubt we can co-opt rolling deep as geologic term with tectonic significance.

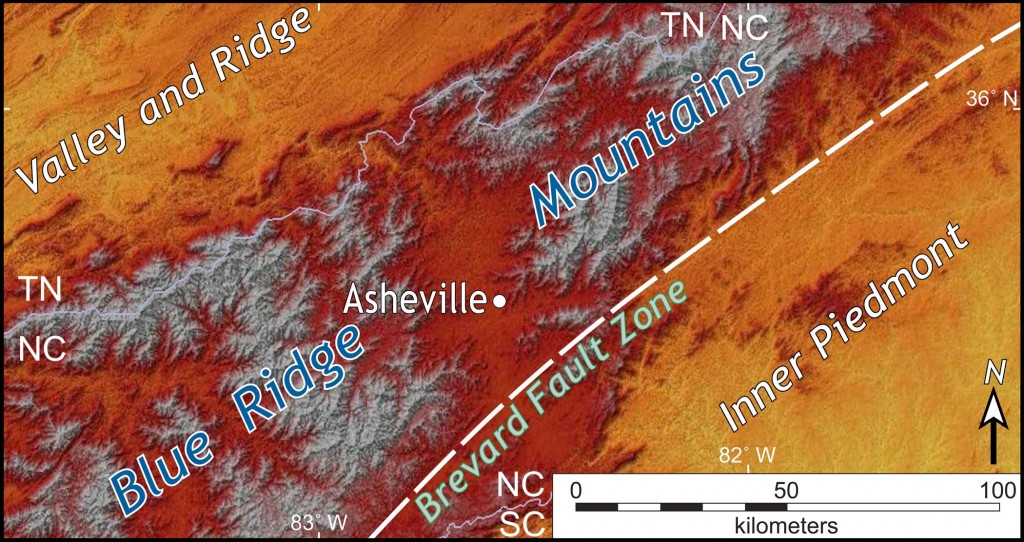

Shaded relief map of the Blue Ridge Mountains and adjacent terrain in the Inner Piedmont and Valley & Ridge provinces of western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee. The Penrose field trip examined rocks across this region.

I learned much about the linkages and feedbacks at work in mountain belts at this Penrose Conference–from the focused erosion in the Himalayan river systems that drive rapid exhumation to the growth dynamics of garnet porphyroblasts in metamorphic rocks from deep in the interior of thrust belts. Heady and exciting stuff!

No comments.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.