Paddle Trip Report 2 – Across the Piedmont and Fall Zone

At the end of my last post we’d completed the first two days of an 8-day canoe trip from the Blue Ridge Foothills in central Virginia to Williamsburg, and were tucked in on a gravelly island in the middle of the Rivanna River.

DAY 3- Rivanna Rain

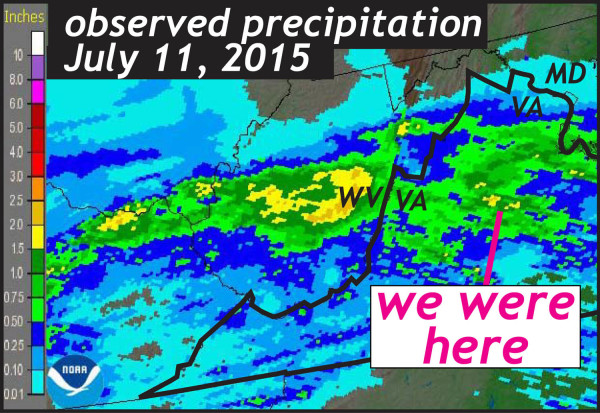

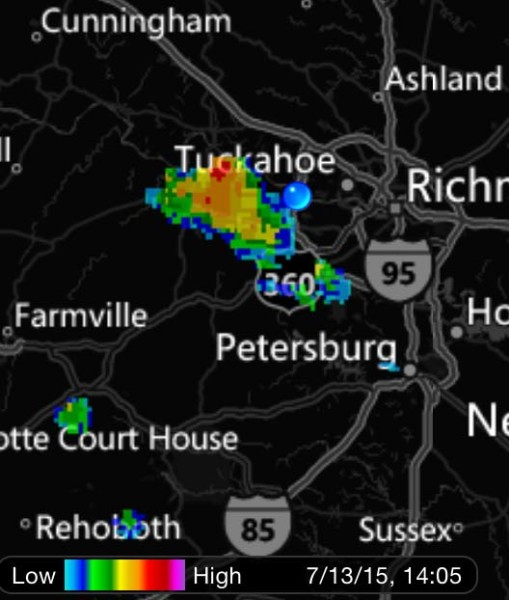

Map of the National Weather Service’s observed precipitation (based on radar data) for Saturday, July 11th 2015. The Rivanna River basin in central Virginia received between 2 and 6 cm (0.75 – 2.25”) of precipitation.

The rain returned during the night. Day 3 started with gray rain on a river that had turned brown from the suspended sediment load. Our first two hours of paddling were in a steady rain that showed no sign of abating. In Fluvanna County, the ever-intrepid Mark Carter (a geologist at the U.S. Geological Survey) put his kayak into the Rivanna and joined the float. Fortunately for us, the rain stopped. We made excellent progress – better than 6 km/hr (~4 mi/hr) down the muddy Rivanna.

We were well out in the Piedmont now, paddling over geologic terranes with complex histories. Near Palmyra, we cruised onto the rocks of the Chopawamsic Terrane, whose volcanic and plutonic rocks formed during the Ordovician period (450 to 470 million years ago). Most researchers now agree that this terrane originated well outboard of ancient North America, and then was accreted to the continent during the multi-act tectonic drama that created the Appalachians.

We traversed over 40 kilometers (26 mi.) on Day 3, and arrived at the old Rivanna Mills in the mid-afternoon. Today the lower Rivanna watershed is wooded and sparsely populated; however, during the 19th century, the region was far less forested, and cleared agricultural lands dominated the landscape. By the 1850s, the Rivanna River was dammed in numerous places. Mills were common, and a canal stretched along its bank from the James River to Charlottesville.

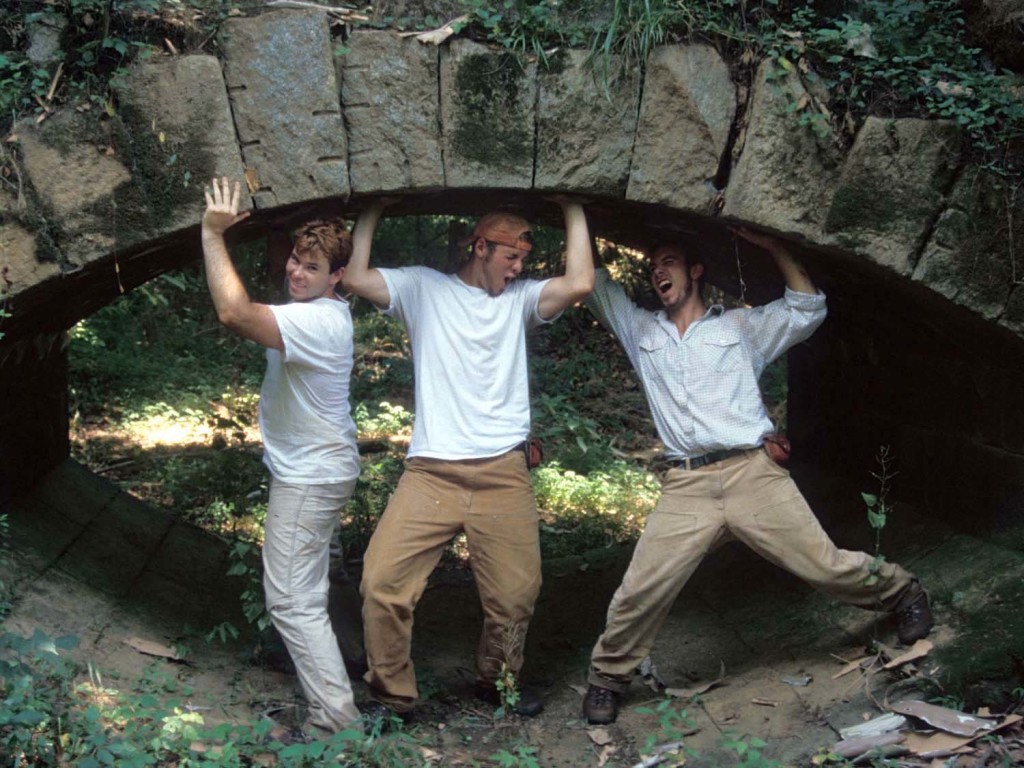

19th century canal works near Rivanna Mills. Geologists are Ethan Weikel, Jon Relyea, and Chris Koteas (W&M Geology, ’02) on a research trip in the Columbia area in 2001. The stone arch (which carried the canal over a creek) is composed of quarried blocks of Ordovician Columbia granodiorite.

Today these old dams are gone, but at certain locations their rocky remains create singular rapids. At Rivanna Mills the washed-out dam forms the largest rapid on the lower Rivanna (a class II rapid with a 1-meter drop and a train of standing waves, watch the action in the video below). We whiled away the remaining daylight hours exploring the overgrown mill, playing in the rapids, and reveling in the sunshine.

Rivanna Mills and the old canal works are massive edifices, constructed from locally quarried blocks of granite and granitic gneiss. It is hard not to ask – whose labor built these structures? As these are pre-Civil War edifices, they were almost certainly constructed by the hands of enslaved people brought as human chattel from Africa. I wonder who were the men, women and probably children whose forced labor resulted in such craftsmanship. But they remain faceless and nameless. For me these beautiful stone structures, hidden away amidst the sprawling green of a Virginia summer, but borne out of an abhorrent socio-economic system present a terrible juxtaposition – one with which the United States still is grappling with in the 21st century.

DAY 4- Raptors Delight

The night was dry, but we awoke to a Rivanna River that was 20 centimeters (8 inches) higher than when we’d gone to bed. Yesterday’s rain had the Rivanna River chugging along at over 1200 cubic feet per second, more than double the rate of the day before – high water for July, but the stream was well within its banks and nowhere near flood stage.

The early morning mist and the fast moving water made for excellent paddling. Without much effort we were reeling down the Rivanna at 8 km/hr (~5 mi/hr). The tree-lined banks seemed to be teeming with raptors – bald eagles and ospreys. As we’d round a bend, they’d take flight from their perches, and in the process put on an aerial show. Over the course of the day we saw dozens of raptors cavorting in the sky over both the Rivanna and James rivers. A decade or two ago, the sighting of an eagle or osprey would have been rare.

Eight kilometers (~5 mi.) down river from camp, the Rivanna had run its course and we floated out onto the wide waters of the James. The morning mist was gone, and the day promised much sunshine.

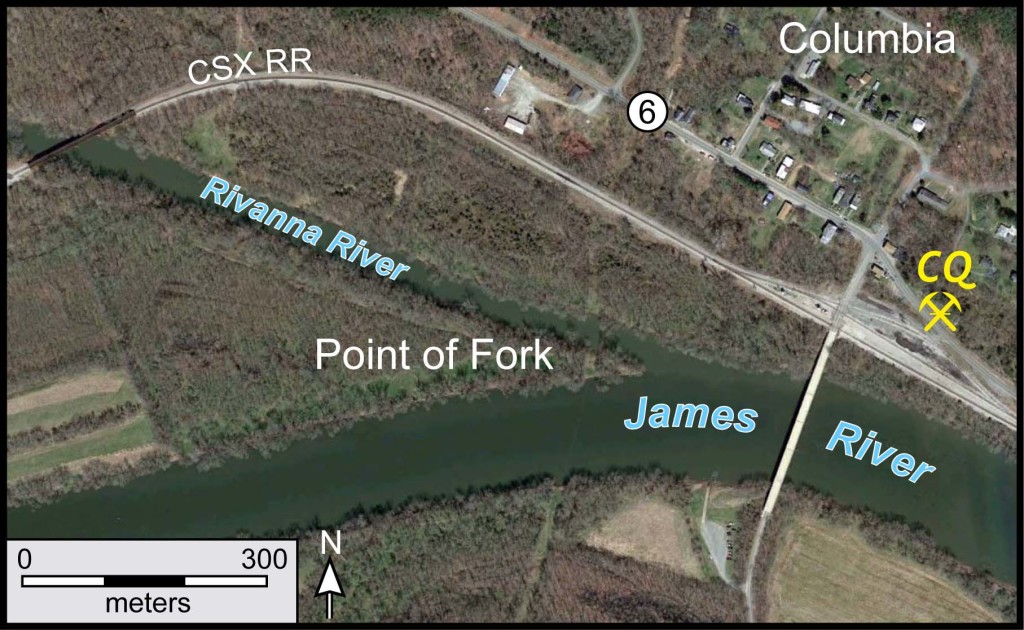

The low alluvial peninsula between the rivers has long been known as Point of Fork, and the modest town of Columbia anchors the north bank. The Monocan town of Rassawek was also sited at this confluence.

The confluence of the Rivanna and James rivers in the central Virginia Piedmont (from Google Earth). CQ- Cowherd Quarry which exposes strongly-lineated granodioritic gneiss of the Ordovician Columbia pluton.

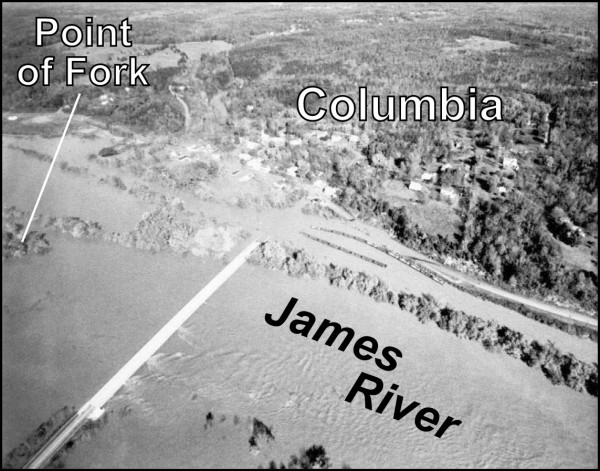

Aerial view of a flooded James River at Columbia, November 1985. Modified from a Richmond Times-Dispatch photo.

Columbia, founded in 1788, has long been Virginia’s smallest incorporated town. The 2010 census tallied 83 people, but many residents view that total as an overestimate. Columbia’s endured its share of hard times and high water from James River floods, the lower parts of town were submerged in 1969, 1972, and 1985.

In March 2015 the citizens of Columbia, by a vote of 18-to-1, decided to unincorporate which means the municipality will likely fall back under the auspices of Fluvanna County. Regardless of the town’s future, I’ll continue to make Columbia a regular field trip stop in my structural geology class as the strongly-lineated granodioritic gneiss exposed at the old Cowherd Quarry is spectacular stuff.

Below Columbia there are no rapids and few riffles on the James. As the current pushed us ever forward, the geologists (there were four of us in three boats) naturally talked geology. In this reach, the James meanders across a wide bottomland that is underlain by alluvial sediment, deposited when the river floods and sediment-rich water spills over its banks.

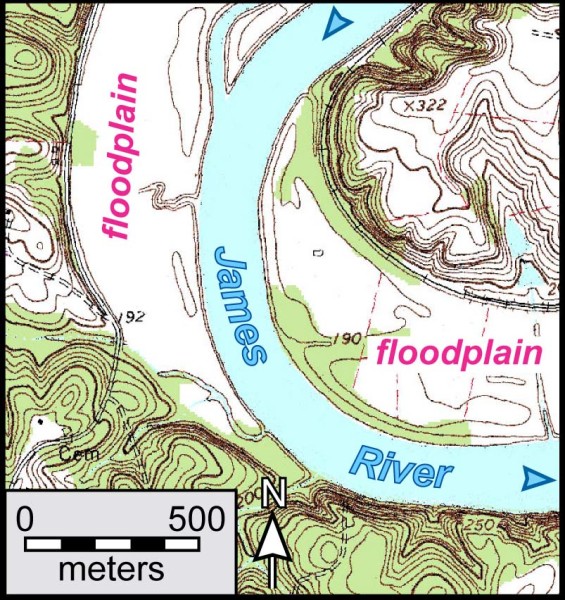

Topographic map of the James River and its floodplain near Cartersville, Virginia. (Contour interval 10′).

The modern channel is hemmed in by steep banks composed of alluvial sand, silt, and mud that rise 3 to 4 meters (10 to 15’). At a number of locations we could see darker, more organic-rich sediment buried beneath a meter or two (3 to 6 feet) of orange-brown silt and sand. The organic-rich sediment was likely the pre-settlement surface of the James River’s floodplain. Prior to colonial settlement in the region, the James River likely had lower banks, but the sediment mobilized by land clearing and intensive agriculture buried the old land surface. The Virginia landscape bears many features that are directly related to both past and present human activities.

At the Cartersville boat landing, we took a break. Here Stuart and Mark left us, returning to the comforts of home. My wife Jennifer, and my colleagues Jim Kaste and Pablo Yañez joined us for Sunday afternoon fun on the river.

The James River had enough flow to move us along without much effort on our part, and the cold beer from our newly replenished cooler hit the spot. Our camp was at the ‘canoe-in’ campground at the new Powhatan State Park, here we enjoyed a tasty and festive dinner. We were nearly halfway home.

DAY 5- The Long Watery Ribbon to Richmond

Once again we awoke to dreary rain, and loaded wet gear into our ‘dry bags’. We said our goodbyes to the overnight crew, and set off towards Pony Pasture rapids in Richmond, some 46-kilometers (29 mi.) distant. Anna Spears ’15 joined us, adding extra paddling power and prowess for this long slog to RVA.

The James River’s gradient as it crosses the eastern Piedmont is quite low, and it’s much made worse by Bosher’s Dam that creates a tepid flat-water river/lake for 15-kilometers (~10 mi.) in the western approach to Richmond. The rain abated, but the air was humid and no doubt more rain was in the offing. Halfway through the long flat-water stretch we looked to the west at a sky that had grown dark – pop up thunderstorms were popping up. Although we missed the first salvo of storms, we were eventually caught up in a proper cloudburst.

We sought shelter from the storm on the James’ south bank, along a pokey little creek (closer to a drainage ditch) very near the Richmond/Chesterfield county boundary. Here we were protected in a low spot, and waited out the storm in the boats. It rained hard, and we bailed steadily (watch the video below).

The rain lasted ~30 minutes, and by the end of the storm the little creek we’d parked in was flowing with some vigor. This small stream, whose basin is less than a square kilometer and drains an upscale suburban neighborhood, was pumping out an unsavory brown mix of sediment-laden water filled with sticks, yard debris, and old gin bottles (all visible at the end of the video). There was also an unpleasant odor riding along with the outflow, perhaps a miasma of vaporized dog poo and fertilizer.

Outline of small drainage basin in west Richmond/Chesterfield County, Virginia. We waited out a thunderstorm here.

After the rain cleared, the sun brightened the scene – we pushed off into the James, and from mid-channel could see that along the south bank, brown water and debris was coursing out of culverts and pipes creating nasty plumes in the river. American suburbs are plumbed to convey sewage and wastewater away for proper treatment, but even still, the detritus of our suburban neighborhoods is not benign. Seeing the effluent of our 21st century life-style, up close and personal, makes a strong case that better environmental stewardship of our waterways is still needed.

Bosher’s Dam was a relatively easy portage. The dam was originally constructed to bring water to grist mills and funnel water into the James River & Kanawha canal in the mid-19th century – today the dam merely clogs up the James River creating a long backwater that provides an ugly patch of water for motor sport aficionados. The Bosher backwater was the least attractive, and most unpleasant stretch of our entire trip.

Damn the Dam 2! Bosher’s Dam in west Richmond. The portage was simple, but paddling the 15-kilometer backwater behind the dam was no fun.

Our final few kilometers were tiring, but we zigged-and-zagged safely through the Pony Pasture rapids to the take-out where Scott’s parents met us. Our longest day on the river came to an end; we retired to the Harris’ house to dry our gear, gobble up a home-cooked meal, and sleep in a bed.

DAY 6- Fall Zone Fury

Mid-Atlantic rivers flowing from the Appalachians to the ocean loose their potential energy in a series of drops known as the Fall Zone, below which the streams become tidal. The James River makes its drop to sea level over a 10-kilometer run that bisects the city of Richmond. Richmond owes its prominence to the Fall Zone, here ocean-going vessels had to offload their cargo and a mercantile center developed.

These big rapids in thoroughly urban environment make the James River in Richmond a classic stretch of white water. I’ve run these rapids many times, and was excited to make our passage. We may be foolish, but we’re not completely stupid, rather than take all our gear through the Fall Zone rapids, we had them transported around the whitewater stretch and filled our canoes with float bags. Richmond native Kelsey Watson ’15 joined us for the day.

William & Mary Geology alums Scott Harris and Todd Beach making it look easy in the Fall Zone rapids in Richmond, Virginia

The James was flowing at ~5,000 cubic feet per second (river level of just above 5’) on the Westham gauge, that’s well above average for mid-July. We set off under overcast skies and moved swiftly down river. Many of the rapids are named, we paddled through the Powhite Ledges, Choo-Choo Rapids, Mitchell’s Gut, and First Break Rapids. The water was up and the river seemed a little pushy.

Hollywood Rapids, just off the north bank of Belle Isle, is a big deal – here the James funnels into a steep drop cut into the granitic bedrock (the 300 million year old Petersburg Granite). It is a big rapid (class III or IV depending on water level) that is also a technical rapid, as it requires a hard left turn to avoid calamity after the drop. We scouted Hollywood Rapids, although I’d seen it flowing at higher levels I’d not been there to run it in an open boat with this much water coursing by.

Kelsey and I hit Hollywood Rapid just right – we stayed balanced, bucked through the big waves and made our left turn. Scott and Todd got to go for a swim at the base of the rapid, but no damage was done. We regrouped and carried on.

The last rapid to run was Pipeline Rapids, where the James makes its final dash to the Tidewater, it is a long set of rapids tucked right against the industrial urban landscape of downtown Richmond.

Kelsey and I were making good progress, but the standing waves were pouring over us. In spite of the float bags, whose purpose is to keep water out and provide buoyancy for an open canoe, we took on water. Water in a canoe makes it heavy and sluggish to control. We were still on our line, bracing to keep the boat balanced, as we entered the final 50 meters of Pipeline Rapids. The canoe raked the bottom causing the boat to yaw and turn broadside in the current. We hit the last rock in Pipeline Rapids, and it rolled us out of the canoe.

We flushed into the James, floated with the rushing water, and navigated slowly to shore. We were wet, but unharmed and in possession of our dry bags. Unfortunately, the canoe was broached and pinned on that last rock. The bow was mostly underwater, the big center float bag kept the canoe off the rock, and the stern sat out of water. Scott and Todd made it through Pipeline Rapids, wet but still in the canoe.

The flow was too great to easily get back to the pinned canoe. Scott and I paddled up in the ‘eddy’ behind the rock; I hopped out and clamored onto the mid-stream rock that was holding the forlorn canoe. Before we had the rescue lines set, the center float bag popped and the old canoe folded around the rock. Had we gotten a rescue line affixed while the stern was up, we could have swung the canoe free with little damage. That did not happen.

After 45 minutes of spectacle, we gave up the rescue effort and I dejectedly hopped off the rock into the whirling James. In six days, we paddled nearly 200 kilometers (120 miles), but now had a busted and broken boat trapped in the Fall Zone’s last rapid.

Things looked grim.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.

Things looked grim? Quite the cliffhanger. I look forward to the resolution.

I personally recommend wearing a helmet in any Rapids class III and up in order to protect those precious geologist brains.