Paddle Trip Report 1 – Through the Foothills

We successfully completed our 8-day paddle trip from the foothills of the Blue Ridge to Williamsburg. It was all the adventure I’d hoped for.

In this first of three posts, I report on the highlights, rough spots, and geology along our journey. This was a personal trip completed with my old friends and goodtime buddies, but I hope that I’ve woven enough geology, hydrology, and natural history into this narrative to make for a worthy read.

The put-in at the confluence of Albemarle County’s Lickinghole Creek and Mechums River. From front to back Scott Harris, Stuart Beach, and Todd Beach. Click on the photo for a larger picture.

DAY 1 – Bumping and Scraping

Early on Thursday, July 9th we launched two canoes onto Lickinghole Creek at its confluence with the Mechums River, near the ever-expanding town of Crozet. The straight-line distance from our put-in point to our take-out at College Creek Landing in Williamsburg is 192 kilometers (120 miles), however rivers trace out sinuous courses, and the actual distance is nearly 300 kilometers (187 miles). Our crew consisted of Scott Harris ’88, Todd Beach W&M ’88, Todd’s son Stuart (W&M class of 2024?), and myself.

The Mechums River is not a big river. Todd kept referring to it as Mechums Creek, and at its modest mid-summer flow that seemed a far better moniker. Our canoes bumped and scraped on the river bottom as we sought fair passage downstream. As anticipated, there were logjams across the channel to push over, under, and through. In spite of our halting progress, the trip was scenic, the water clear, and all in all it was a fine day to be on the river.

In central and northern Virginia, most streams draining the eastern slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains flow more-or-less to the southeast, directly away from the highlands. The Mechums River cuts a different course, flowing primarily to the northeast. What roll does the underlying bedrock play in the character of a stream and its drainage basin? It’s a question geologists like to ask.

The bedrock beneath the Mechums River consists of metamorphosed shale (now phyllite) and gritty sandstone – these metasedimentary rocks crop out in a narrow (<2 km wide) northeast-trending belt surrounded by older granitic rocks on either side. Some geologists have suggested these metasedimentary rocks fill a fault-bounded graben, but our research indicates that’s not the case, rather the Mechum River belt* is a synclinal structure bordered by a reverse fault on only one side.

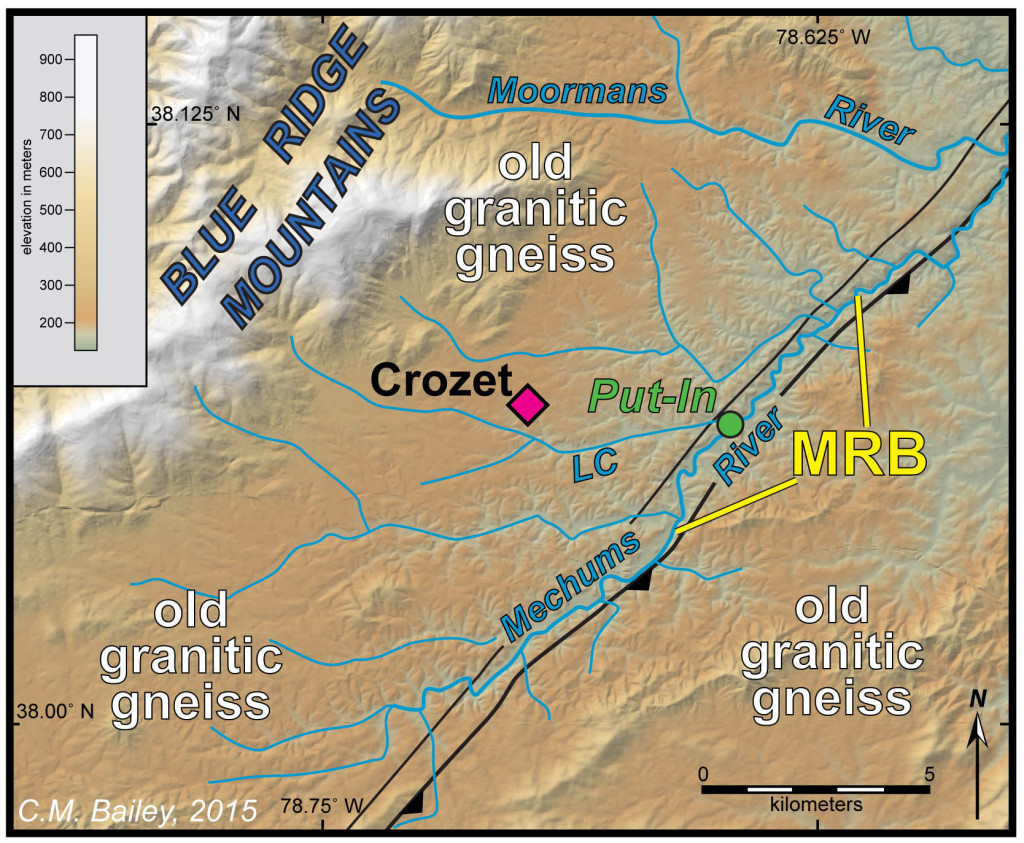

Shaded relief map with simplified geologic map of the Crozet area and the Mechums River, Albemarle County, Virginia. LC – Lickinghole Creek, MRB – Mechum River belt* (Neoproterozoic metasedimentary rocks). The thick black line adorned with triangles is a reverse fault.

Interestingly, the Mechums River flows parallel to the belt of metasedimentary rocks, and it’s likely that this belt of weaker and more erodible rocks influenced the course of the Mechums River. If you are interested in examining the metasedimentary rocks exposed in the Mechum River belt* consider joining us for a Geological Society of America field trip in late October.

The Mechums and Moormans rivers converge to become the South Fork of the Rivanna River, and the increased flow made for easier paddling. We saw our first bald eagle of the trip on the South Fork. The afternoon was hot and our last few kilometers required steady work over the flat-water impounded behind the 10-meter (~35’) tall Rivanna dam.

Courtesy of the Murray family, we camped at Panorama Farms, which is a prime cross country venue for both high school and college athletes. It was nice to see the placards denoting that William & Mary’s Elaina Balouris and Emily Stites hold the collegiate women’s records for the 5k and 6k courses at Panorama Farms. Go Tribe!

DAY 2 – Traversing Jefferson’s Country

After a fitful night of sleep, we packed and then paddled the final 5-kilometers (3 mi.) across the Rivanna Reservoir, much of it in the company of crew teams training on the flat water. Our portage around the Rivanna dam was a challenge that involved carrying two canoes and a week’s worth of gear more than 400 meters (0.25 mi.) to reach the flowing waters below the dam.

Damn the Dam! The Rivanna Dam and the free flowing river downstream. Portaging this dam was unpleasant.

We rounded the eastern edge of Charlottesville on the Rivanna; this was no wilderness stream, but the riparian vegetation along the riverbanks kept much of the development hidden from our view.

Just southeast of Charlottesville, we passed beneath Interstate 64 (the more normal route between Charlottesville and Williamsburg), and the Rivanna River cuts a long water gap between the Southwestern Mountains and Jefferson’s Monticello. This is a wonderful stretch of river; replete with rapids and remarkably clear water.

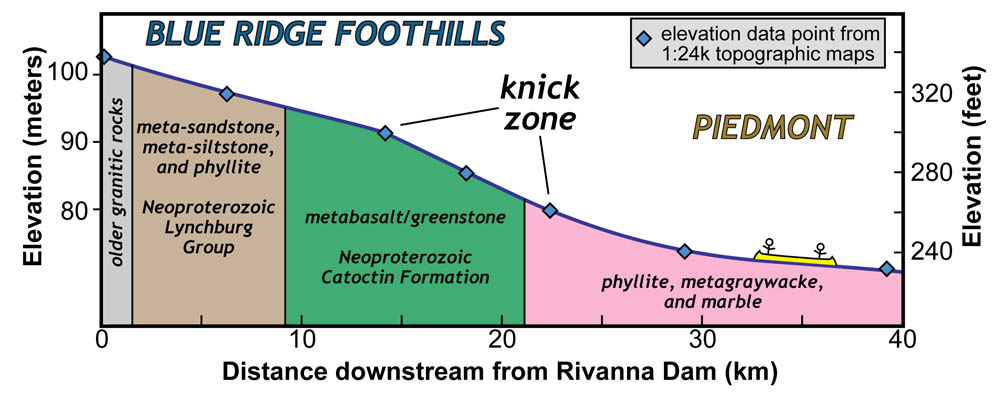

Here metamorphosed basalts of the Catoctin Formation underlie the river, these tough rocks create a noticeable knick zone as the Rivanna transits from the Blue Ridge Foothills into the Piedmont. But here is a question – is this knick zone a stationary or migratory knick zone?

Stream profile of the Rivanna River in the Blue Ridge Foothills and Piedmont. Note the knick zone in the Catoctin Formation. Profile based on data from 1:24,000 scale USGS topographic maps. Is this a stationary or migratory knick zone?

Our second day on the river ended with a thunderstorm that harried us all the way into camp on an alluvial island in mid-channel. However, the rain passed, and we ate our dinner unmolested in the evening sunshine.

* the stream is the Mechums River, but when first introduced into the geological literature the rocks in the belt that parallels the river were named the Mechum River Formation (without the s), thus the difference in spelling between the geographic and geologic features.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.

I love the way you integrate your geological ponderings into the larger narrative. A nice illustration of how a knowledge of scientific principles and concepts can enrich any experience.