Earth Structure & Dynamics: Dreaming in 3D

One of the courses I am teaching this term is Earth Structure & Dynamics (GEOL 323), a second-level geology course, and a required class for all Geology majors. This course combines structural geology, tectonics, geophysics, and a pinch of historical geology. Thirty-four students enrolled in this year’s class, that’s plenty, and free seats are hard to come by in the classroom.

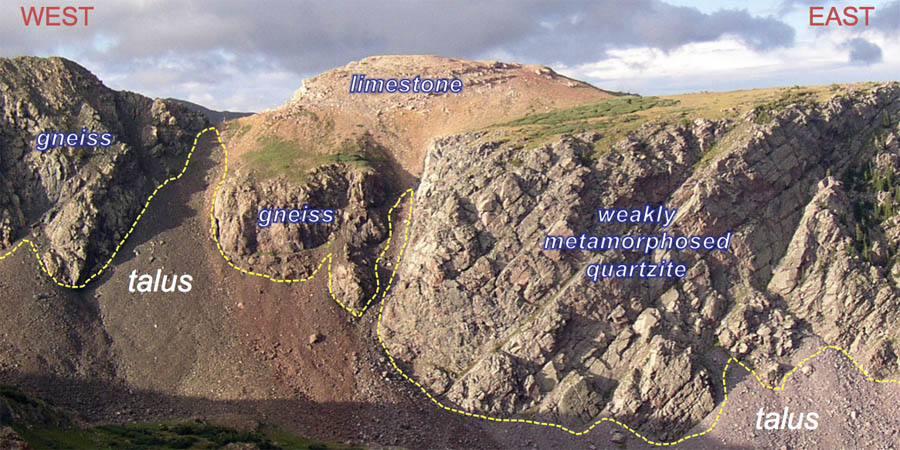

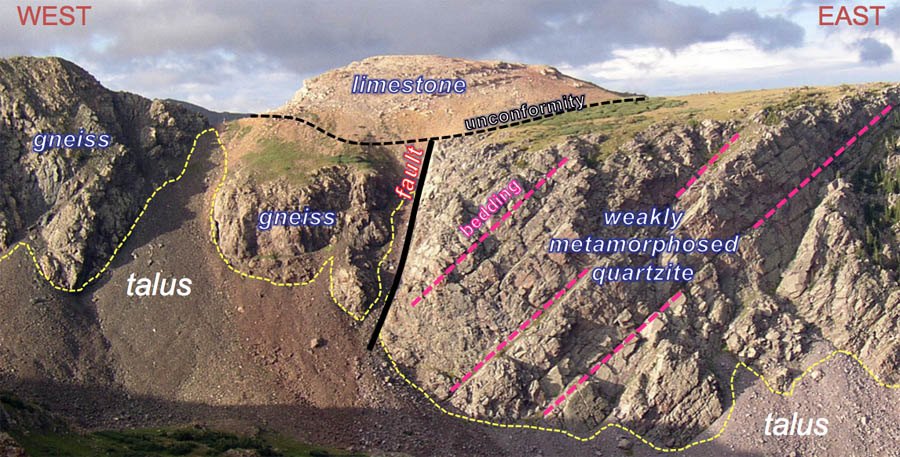

As you might guess from the course title, I want students to be well versed at recognizing and understanding how earth structures form. What is an earth structure? Anticlines, reverse faults, half-grabens, stretching lineations, and boudinage (to name a few). This requires three-dimensional thinking, and 3D thinking requires much practice. On Friday, I projected an image of a craggy mountain side in the Needles Mountains of southwest Colorado and asked the class to 1) sketch the geology, 2) identify the salient geologic structures, and 3) work out the temporal history of the geologic events. I annotated the image such that different rocks and surface landforms are illustrated. Talus is rocky debris that has accumulated at the base of the cliffs: I want the students to “see through” the talus to visualize the underlying bedrock structures.

View of mountain side above Dollar Lake in the Needle Mountains, Colorado with geologic materials labeled.

The limestone crops out above both the gneiss and quartzite, and it is the only one of the bunch that’s not been metamorphosed, therefore it is the youngest rock in the scene. But which of the metamorphic rocks is the oldest? The class struggled with this one. From the image alone the age relations are not discernible, but notice the quartzite is weakly metamorphosed (in contrast to the gneiss, a well-metamorphosed rock) and the original layering (bedding) is evident. Based on this information the quartzite is younger than the gneiss.

The boundaries between the different rock types are structures (referred to as geologic contacts). The limestone overlies the older metamorphic rocks along an unconformity, whereas the gneiss and the quartzite are juxtaposed across a fault (but just what type of fault?). Many students overlooked the significance of these geologic structures, but with practice, these abominations will stop!

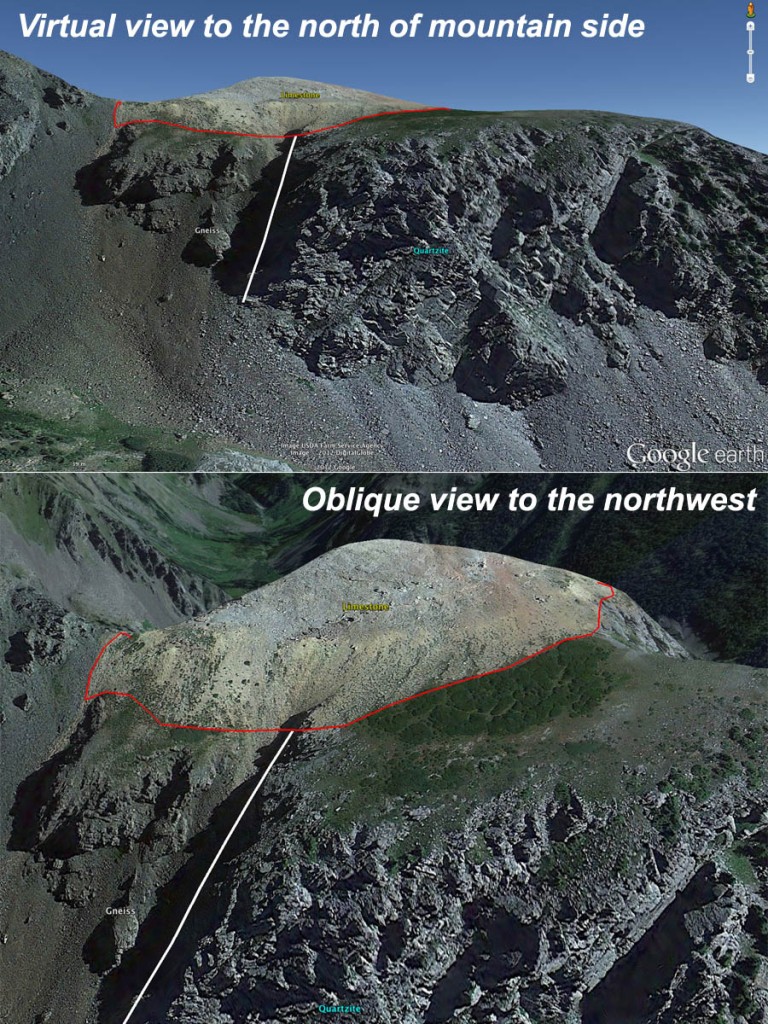

The photo is two dimensional, but how best to help bring out the third dimension? Google Earth to the rescue—we zoomed from space into the Needle Mountains to about the same vantage point as the field photo was taken. With the tilt, pan, and zoom function it was easy to see the steep slopes of talus and that the limestone forms an erosional cap above the older metamorphic rocks. We will use overlays and tours in Google Earth to hone our visualization skills in the coming weeks. I want the Earth Structures students to translate from 2D to 3D without a hitch, by the end of the semester they’ll be dreaming in 3D!

So what is the temporal history of the geologic events? Here is my interpretation from oldest to youngest:

- formation of the protolith for the gneiss

- burial and metamorphism to form the gneiss

- uplift and erosion

- deposition of sand that forms the protolith to the quartzite

- burial and metamorphism affects the gneiss and creates the quartzite

- tilting

- faulting juxtaposes the gneiss and quartzite

- erosion

- deposition of the limestone

- minor tilting

- uplift

- erosion to form the modern topography

- I take the picture

What the Geology 323 students worked out was the relative timing of geologic events, a fundamental skill for earth scientists. The next logical step would be to determine when, in absolute terms, these events occurred—that comes later in the semester when we delve into geochronology.

No comments.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.