A Frenzy of Fall Field Trips 4: Spy Rock

Once again, the 2019 Geological Field Methods class was on the move this past weekend. We were on a mission to collect a suite of samples for isotopic dating that will help us better understand the geologic history of the ancient rocks that underlie the Blue Ridge.

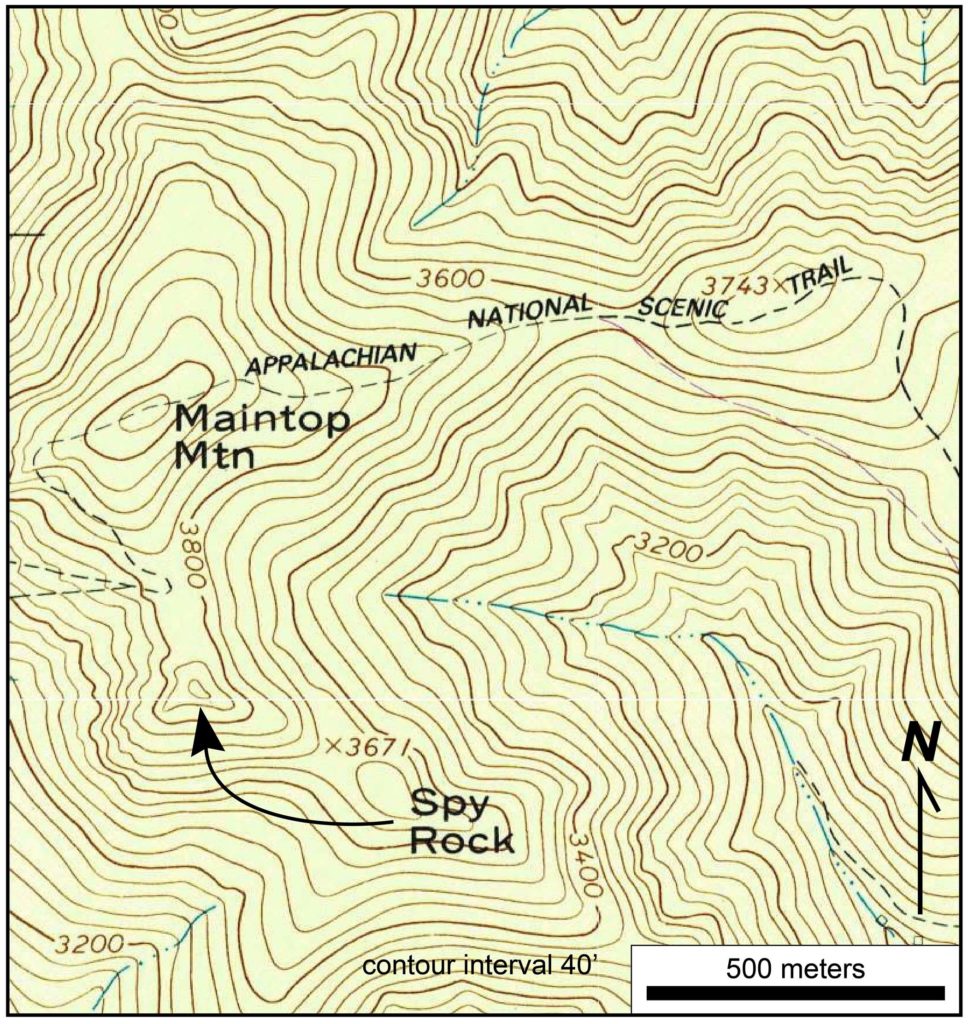

The high point of our day (both literally and figuratively) was Spy Rock, located on the southern shoulder of Maintop Mountain. Spy Rock tops out at 1,190 meters above sea level (3,900’). The view from Spy Rock is impressive as landmarks 100 km (60 miles) away in the Shenandoah Valley and Piedmont are visible.

Topographic map of the Maintop Mtn. and Spy Rock in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Nelson County, Virginia.

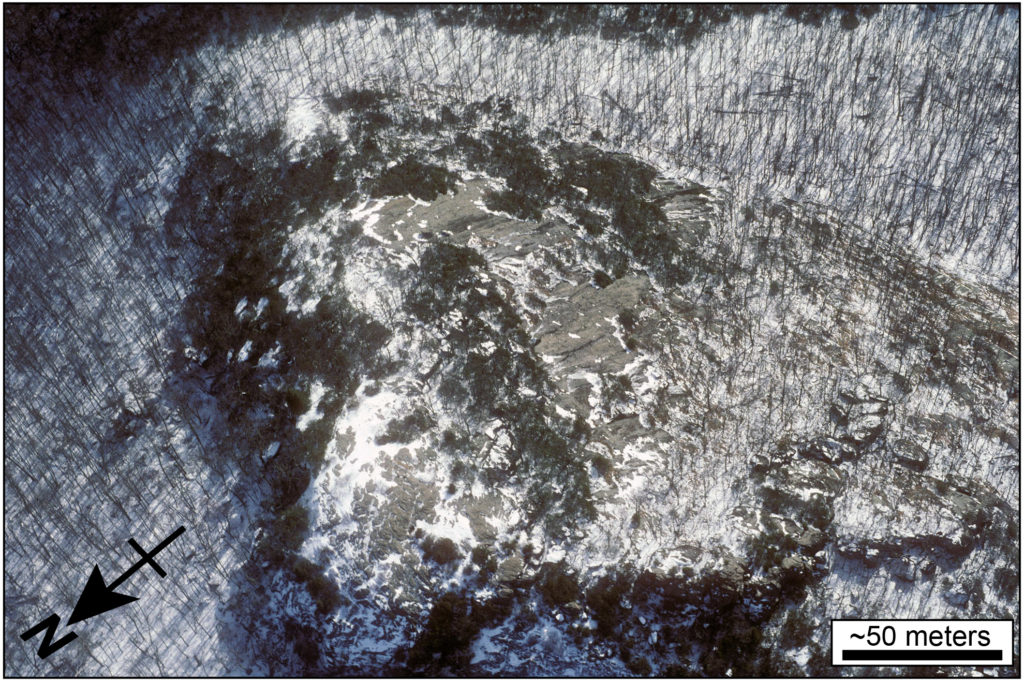

Spy Rock is an expansive patch of granite, or more specifically a charnockite (a pyroxene-bearing granite) that forms a rocky dome framed by gnarled oaks and grassy heath. It’s also home to a distinctive flora of herbs that are well-suited for the difficult life atop a rocky bald.

Low altitude aerial photo of Spy Rock (C. M. Bailey photo from Dec. 1996). Click on the photo for a larger image.

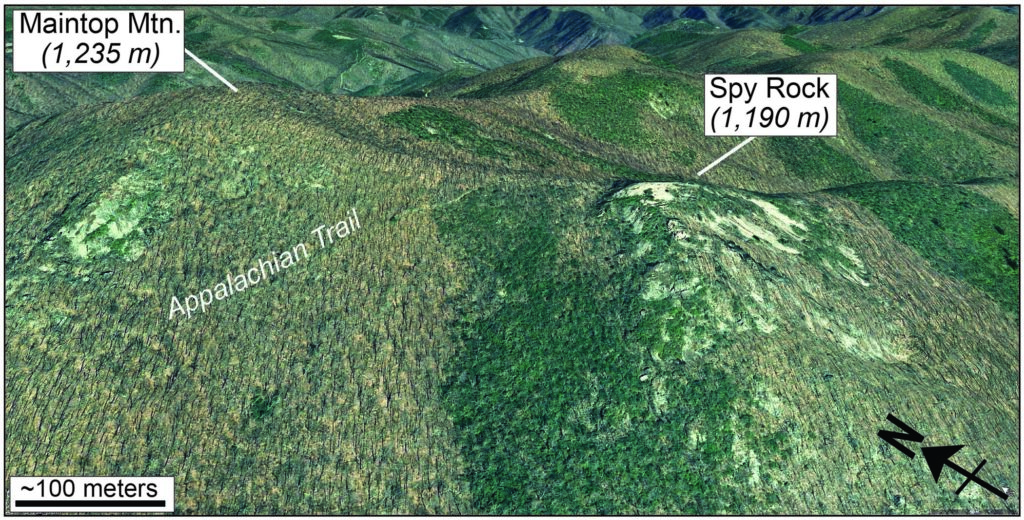

As we reveled in the crisp weather and magnificent views, I asked the class why Spy Rock is there in the first place. All around us we could see mountain after mountain covered by forest. Even in this steep landscape, rock outcrops make up a small proportion of the landscape.

Some students suggested that the rocks at Spy Rock are especially difficult to erode, while others argued that, perhaps there was some event which removed the regolith and exposed the bedrock.

Oblique Google earth view of Maintop Mtn. and Spyrock. Note all the forest cover with lesser expanses of bedrock. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Debris flow scars from the August 1969 Hurricane Camille event in Nelson County (photo by Virginia Division of Mineral Resources).

What kind of event could bring on such change? Glaciers are effective agents at removing regolith and exposing the underlying bedrock, but not even the highest peaks in the Virginia Appalachians were glaciated during the last Ice Age. Maybe mass wasting was the responsible process? 50 years ago, the remnants of Hurricane Camille dumped >50 cm (>20” inches) of rain on the Blue Ridge foothills in eight hours causing thousands of debris flows that exposed bedrock in steep first-order hollows.

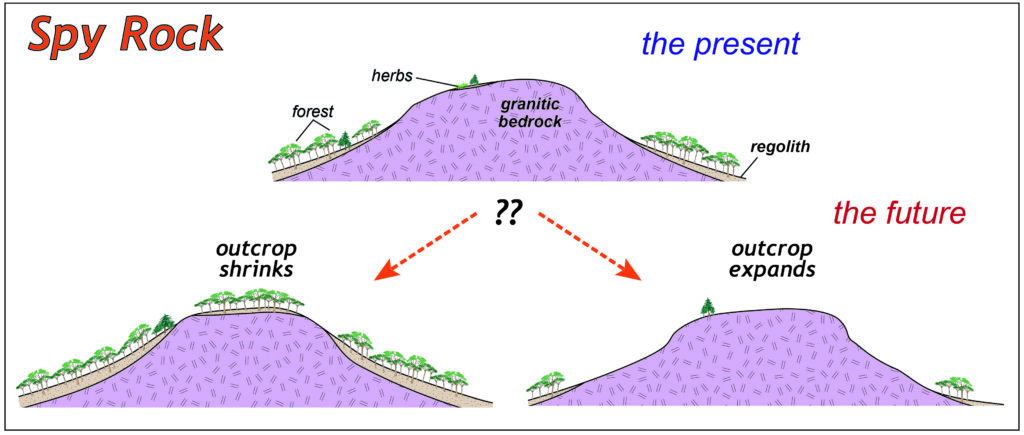

I then pitched another question: is Spy Rock expanding or shrinking? Put another way, if one were to come back to Spy Rock in a century, would its rocky footprint have grown or would plant succession have successfully cloaked Spy Rock with forest?

No consensus was reached regarding the origin or fate of Spy Rock. 🙁

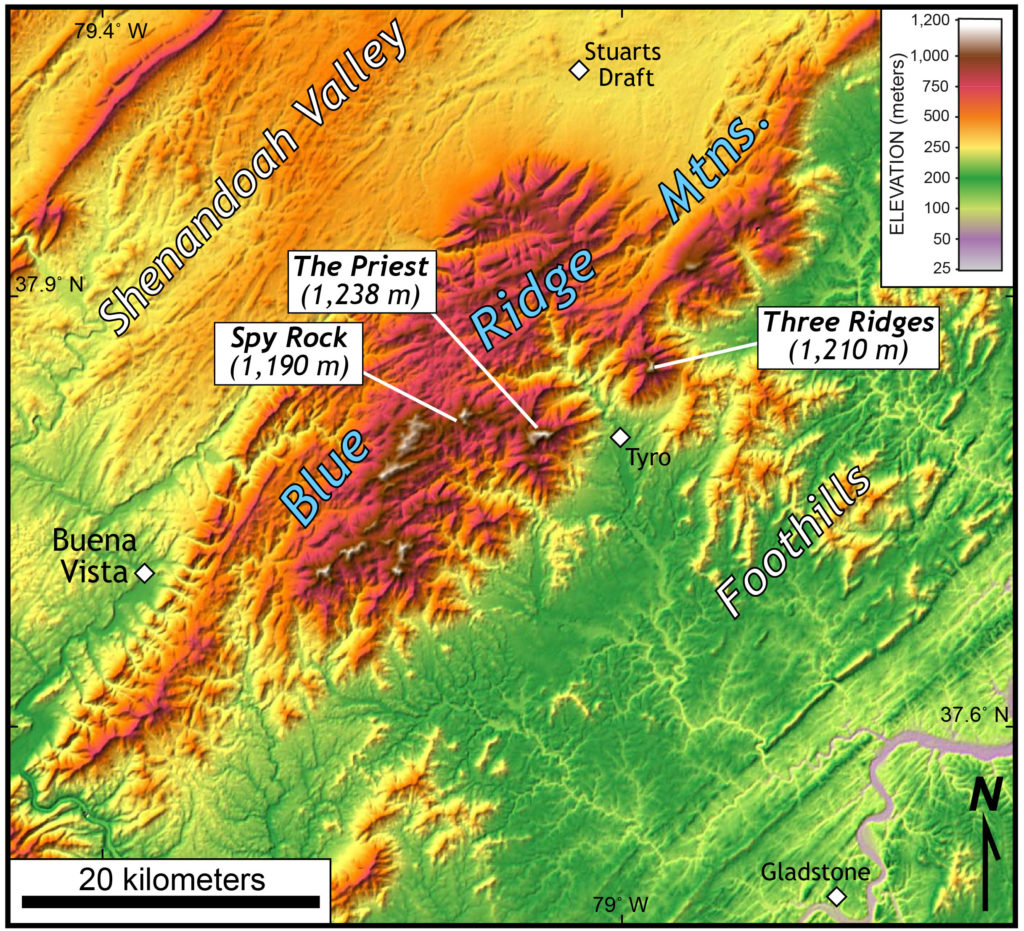

We traveled from the crest of the Blue Ridge to the base of the range along the Tye River valley near Tyro. In central Virginia, the tallest peaks in the Blue Ridge top out at just over 1,200 m (4,070’). From the high summits of the Priest and Three Ridges the terrain drops more than a kilometer (>3,300’) to the Tye River valley- this scenic region has some of the greatest topographic relief in the Appalachian Mountains.

Shaded relief map of the central Virginia Blue Ridge, Foothills, and the Shenandoah Valley. Note the dramatic change in elevation between the Priest and Tyro.

How was this much topographic relief generated? We contemplated two hypotheses: active tectonics and differential erosion. We also pondered whether the topographic relief is increasing or decreasing. Again no consensus was reached. 🙁

Oblique aerial photo (view to the southwest) of the central Virginia Blue Ridge. Note the dramatic relief between the crest of the mountains and the Tye River valley (C. M. Bailey photo from Dec. 1996).

We go to the field seeking data to answer geological questions, yet many times we come away from the field with more questions than answers. The samples we collected will ultimately inform us about the exhumation history of these ancient rocks, and hopefully shed light on the timing of mountain formation and topographic relief generation in the Blue Ridge.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.

One of the best/worst/most frustrating/most motivating things about learning from you was that I always got the sense you had a really convincing answer to all your questions that eventually you would share with us. And that all your devil’s advocacy was designed to lead us to that answer. 15 years later, I FINALLY am starting to grasp that you just love a good controversy. Haha.

P.S. I vote for outcrop shrinkage

Indeed, a good controversy is great! I agree that Spy Rock is likely to shrink with time, episodically shrink as primary and succession work. All that topographic relief is likely due to a combination of 1) the legacy of the Atlantic rift-shoulder migrating westward, 2) differential erosion, and 3) perhaps a little nudge from mantle flow in the Cenozoic. However, I’m not fully confident that these factors have to be the cause of Blue Ridge relief.

Our low-temperature thermochronology data should help to define a exhumation path and erosion history for this region.

A mostly un-qualified answer! Wow! 😉

Looks like you all are having a great semester.