Geologists Siege Yorktown

Yorktown’s most famous siege took place in 1781, when American and French troops surrounded General Cornwallis and the British forces. Ultimately, the British capitulated and the American Revolution was effectively won at Yorktown – it was a big deal. For more than a decade now, William & Mary geologists have repeatedly sieged Yorktown during the first field lab in the Earth Structure & Dynamics course.

On Monday and Tuesday, we were back in Yorktown on a two-fold mission to 1) practice doing geology in the field, and 2) learn about the geology underfoot on the Atlantic Coastal Plain.

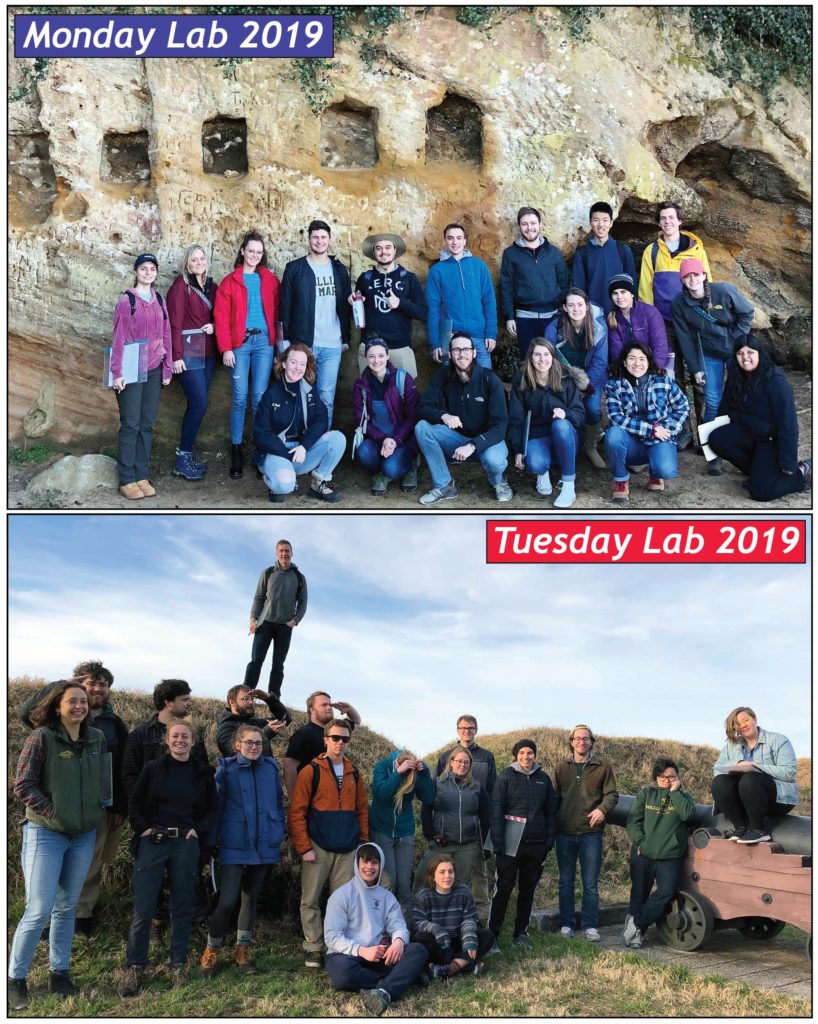

The 2019 William & Mary Earth Structure & Dynamics lab sections at Yorktown. The Monday lab at Cornwallis Cave and the Tuesday lab at the 2nd French Siege Line.

Our first activity involves measuring a set of compass bearings, and then using a bit of trigonometry to estimate the width of the broad York River estuary. Curiously, the trigonometry typically proves to be more challenging than the compass measurements.

Top – W&M geologists at work measuring bearings to determine the width of the York River estuary (2015). Bottom Left – The challenge of measuring a bearing on a rainy day (2013). Bottom Right – This is no event! Working out the trigonometry to estimate the width of the York River (2014).

We also descend upon a 21st century rip-rap revetment/breakwater. It’s an engineered structure placed along the watery edge of the beach, designed to slow shoreline erosion. These extraordinarily large blocks include a diverse suite of rocks and structures. The rip-rap was quarried from igneous and metamorphic rocks in the Piedmont and shipped by barge to the Yorktown waterfront. Perfect practice to ready ourselves for our field trip to the Appalachian Mountains in April.

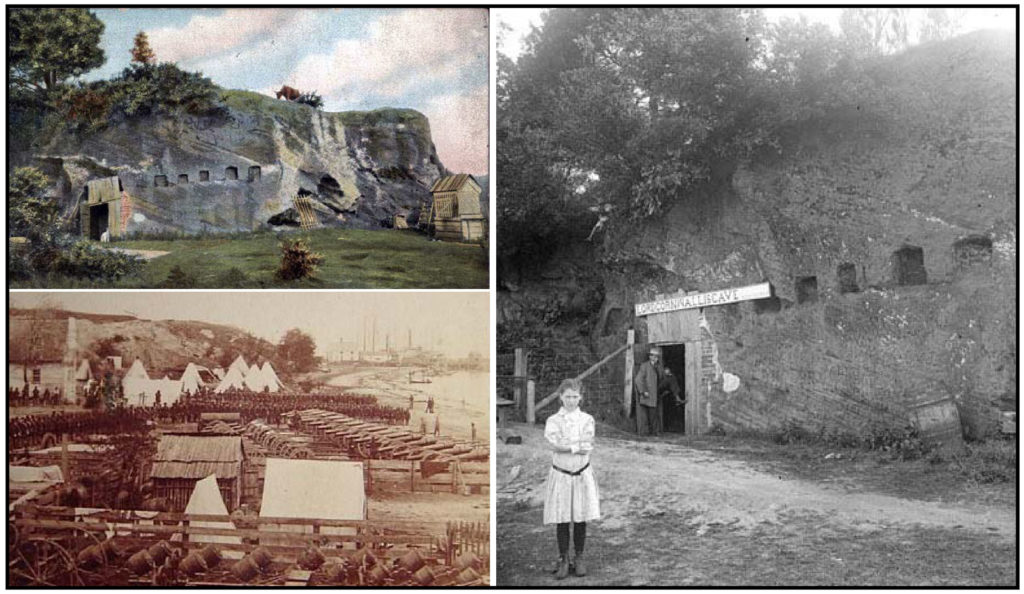

From the modern shoreline defenses, we roll onward to Cornwallis Cave, a historic natural outcrop on the Virginia Coastal Plain. The cave is a manmade chamber carved out of the rock. During the siege of Yorktown, the Allied artillery shelled the British positions, and as the story goes, General Cornwallis sought shelter in this grotto. However, National Park Service research suggests the Cornwallis story to be apocryphal. During the Civil War munitions were stored here, and large square recesses were cut to support a plank roof that extended outward from the cliff. In the early 20th century, Cornwallis Cave was something of a tourist attraction.

Top Left – An ‘old school’ postcard of Cornwallis Cave from the early 20th Century. Right – Lord Cornwallis Cave in 1915, note the inclined strata evident on the cliff face. Bottom Left – A Civil War view of Federal equipment at Yorktown, the view is to the northwest, Cornwallis Cave is at the base of the bluffs in the background.

The Coastal Plain is underlain principally by unconsolidated sediment, that is sediment which has not been cemented into rock. Thus, the exposure at Cornwallis Cave is unusual as the sediment actually holds together and is justly described as rock. It’s an indurated biofragmental sandstone, also known as coquina. The calcareous sand ranges from fine to granular and is composed primarily of fragmented bivalve shells (with an assortment of other organisms). The carbonate content in the rock is >90% with the remainder consisting of Fe-oxides, quartz, and clay minerals. The rock is porous and exceptionally permeable which 1) enables groundwater to easily percolate through the rock and 2) precipitate mineral deposits that cement the sediment together. In the colonial era, this rock was quarried for local building foundations. It’s not a particularly durable rock, but it was handy.

Katharine Celata and Monica Stone with compass plate and Brunton measuring the orientation of inclined strata at Cornwallis Cave (2012).

Sedimentary layers that underlie the Coastal Plain are typically flat-lying or horizontal, and faithfully reflect the orientation in which the strata were originally deposited. But at Cornwallis Cave, our attention is piqued as the coquina layers are moderately inclined. One of our main tasks at the outcrop involves measuring the three-dimensional orientation of the layers using the Brunton compass. The outcrop surface is a cliff and generally not parallel to the layers, so we use our field clipboards as compass plates, holding them parallel to layering and measuring the strike and dip of the field clipboard as a proxy.

Measuring rocks structures with a Brunton compass takes practice, and the 2019 class is still cutting its teeth. Improvement will follow.

After making observations and measuring geological structures, we come up with a set of hypotheses to explain the orientation of layering. As I noted above, all across the Coastal Plain the strata are nearly horizontal – why are the strata at Cornwallis Cave inclined?

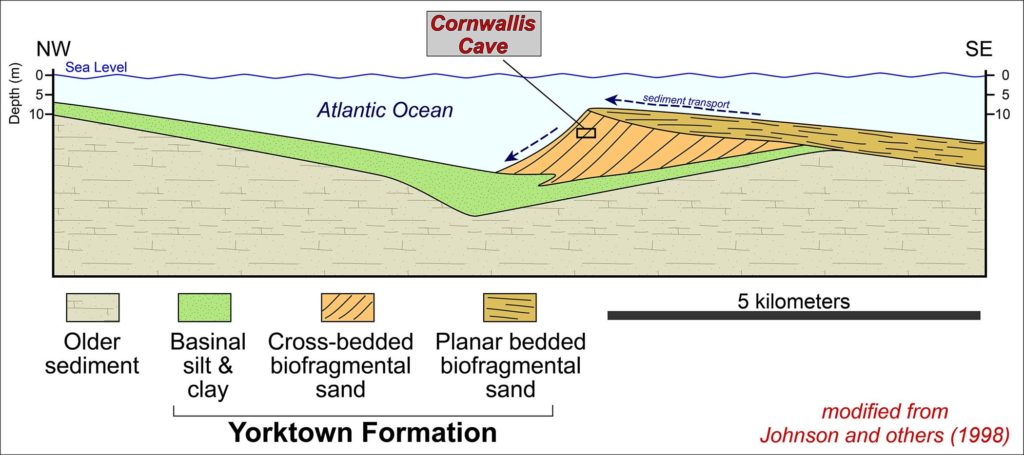

One hypothesis is that the layers of broken shells accumulated in a horizontal position and were later tilted by tectonic activity. A competing hypothesis posits that the strata were deposited on an incline and never tilted. In certain depositional settings, such as on large dunes or submarine shoals, layers may be deposited at angles upwards of 30˚. At the base of the dune or shoal, these cross-beds become less steeply inclined and pass into a nearly horizontal orientation.

How, in the field, do we evaluate these two hypotheses?

We look at the outcrop once more. A close examination of the outcrop reveals fossil burrows (Ophiomorpha) in a nearly vertical orientation. These burrows disrupt the inclined layering, and their vertical attitude indicates that the strata were deposited on a slope. If the layers had been tilted after deposition, we’d expect the Ophiomorpha burrows to not be vertical.

The inclined strata at Cornwallis Cave are part of a cross-bedded carbonate sequence that was deposited on the northwest edge of a submarine shoal or bar. Here in the shallow water, great quantities of shelly sediment were thrashed about and broken by waves with the sandy bits and pieces flushed over the shoal and down the steep leeward slope into deeper water.

Cross sectional interpretation of depositional environments associated with a submarine shoal during the deposition of the Yorktown Formation (modified from Johnson and others, 1998).

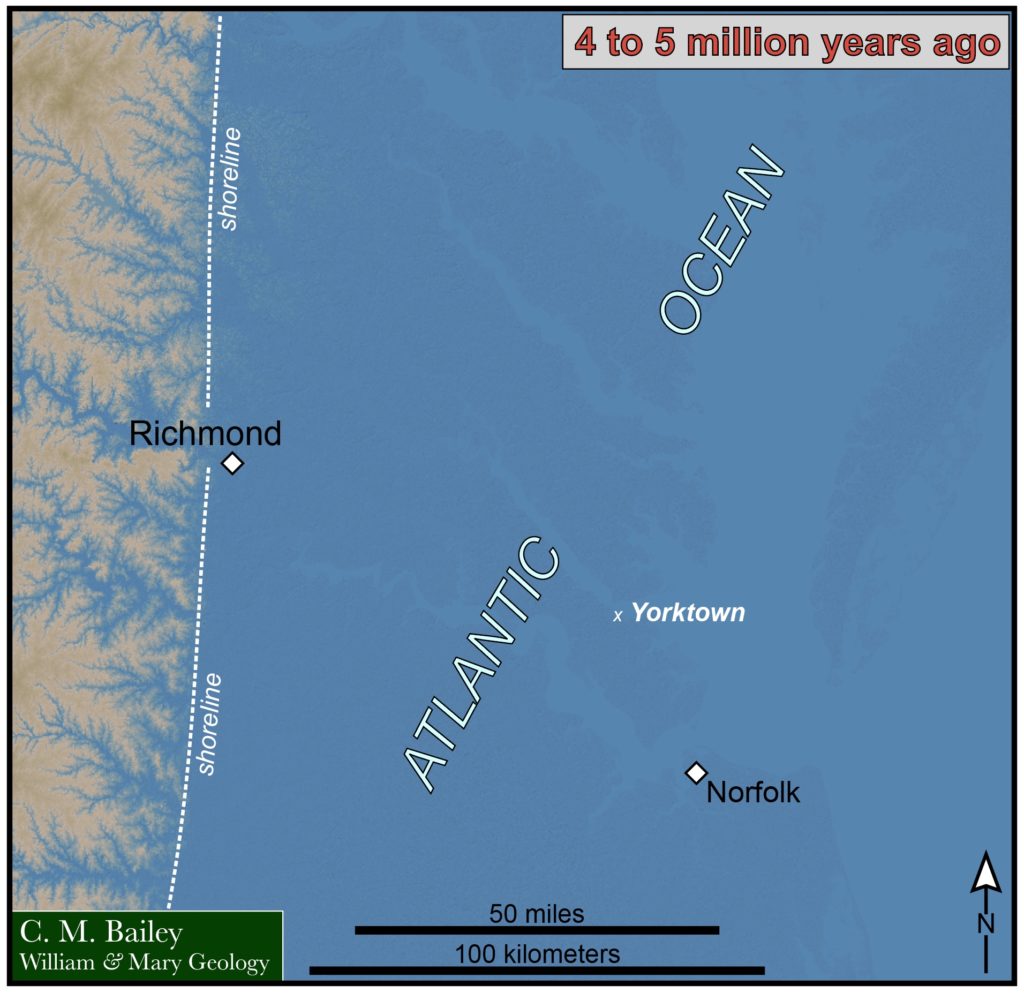

The strata exposed at Cornwallis Cave are part of the Yorktown Formation, a widespread Pliocene marine deposit that underlies most of the Virginia Coastal Plain. The Yorktown Formation was deposited between 4 and 5 million years, when the ancient Atlantic Ocean’s waters reached as far west as Richmond (well, the area that would eventually become Richmond). These were subtropical seas with a plethora of organisms flourishing in its warm shallow waters.

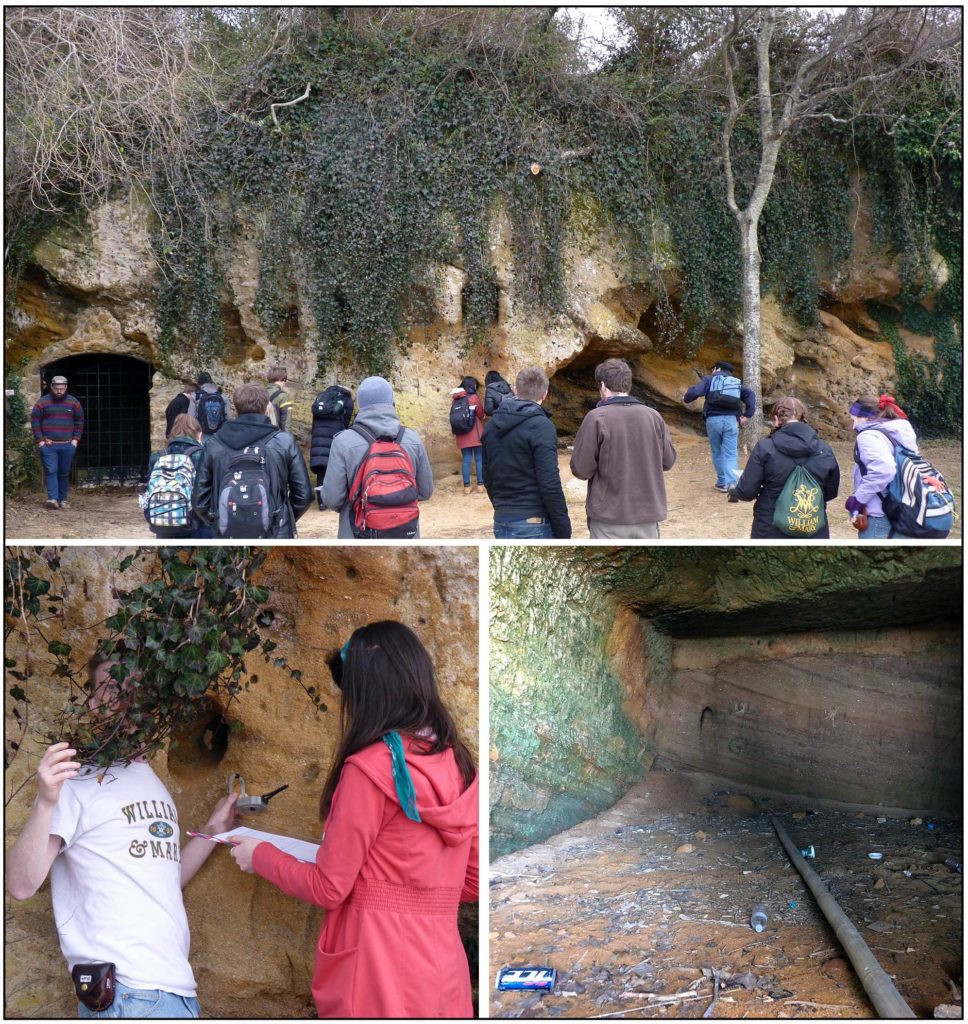

I now have a 12-year time series from our yearly trips to Cornwallis Cave. The photos illustrate that the outcrop is suffering from a number of ailments, the most obvious are the festoons of English Ivy (Hedera helix) that seemingly cascade down the cliff face. In this setting, English Ivy is an invasive species and it’s hastening the weathering and disintegration of the outcrop.

Top – A 2014 image of Cornwallis Cave. Note the invasive English Ivy (Hedera helix) cascading down the cliff face. Bottom Left – English Ivy consumes Ben Weinmann in 2015. Bottom Right – The interior of Cornwallis Cave in 2019, note the Bud Ice beer can for scale and the inclined strata.

Perhaps, General Cornwallis is exacting his revenge – English Ivy is destroying an important natural and historic American landmark at the very site where the United States won its independence. How cheeky!

Something should be done to remediate this abomination. A first order fix would be to turn some patriotic goats loose on the English Ivy and other encroaching vegetation. After the goat platoon finishes its job, it’d be reasonable to gently power wash the cliff to remove the clingy bits of ivy rootlets and the myriad of microbial mats that currently coat the outcrop.

The National Park Service maintains the Yorktown Battlefield as part of the Colonial National Historical Park, and is rightly concerned about deteriorating conditions on the inside of Cornwallis Cave (which is not accessible to the public). They should also be concerned about the exterior. Were this a historic building entrusted to the Park Service every effort would be made to preserve the structure for future generations, yet Cornwallis Cave suffers from benign neglect.

The exposures at Cornwallis Cave are an important and accessible piece of America’s geological heritage, one that’s also intertwined with the final chapter of the American Revolution and our awful Civil War. That is certainly worth preserving.

A few years hence, it’d be awesome to showcase photos of a crisp and clean Cornwallis Cave in all its geological splendor. We’d be keen to work with the Park Service on the preservation effort.

The last stop on our geological siege of Yorktown takes us to the 2nd French Siege Line where we delve into a bit of interdisciplinary learning. Just as we’ve done since the first Earth Structure & Dynamics field trip to Yorktown in 2007, long before the COLL curriculum or interdisciplinarity became cool at W&M, students put themselves into character as a young staff officer serving the French field commander the Marquis de Lafayette.

Marquis de Lafayette orders to his staff officers. Note the novel use of an American five dollar bill to measure the map scale!

Lafayette asks the officer for the range and bearing to British Redoubt #9, so as to better train the battery of French cannons on the enemy’s position. Once again we employ our compass and some geometric know-how to provide the solution for Lafayette. The fall of British Redoubts #9 and #10 to French and American infantry on October 14th 1781 was the master stroke of the battle, as the Allied forces could then shell Yorktown at will. Soon after the redoubts were captured, Cornwallis asked for surrender terms.

Our yearly siege of Yorktown is all about doing geology outside the classroom, but with a historic twist. For me it’s a late winter adventure that I look forward to because it builds community and we put into practice what we’ve worked to learn in the lab.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.

Another great blog. I would love to see that outcrop cleaned up of the ivy as well as the bamboo. I certainly remember having trouble with the trig. I later realized I had all trig functions at the back of my field book, since I bought the engineer’s field book instead if the geologist’s field book.

I’m so glad my bottle made it into the final draft 🙂