Rabble with a Cause- W&M Geology at Menokin

Menokin is an 18th Century Georgian-style plantation house on Virginia’s Northern Neck, which was the residence of Francis Lightfoot Lee and Rebecca Tayloe Lee. Back in 1776 Francis Lightfoot Lee was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, but today his house lies partially in ruins, as much of the structure collapsed in the mid-20th Century. The Menokin Foundation has taken on the ambitious task of ultimately restoring this old stone house; they’ve got a great tagline – Rubble with a Cause.

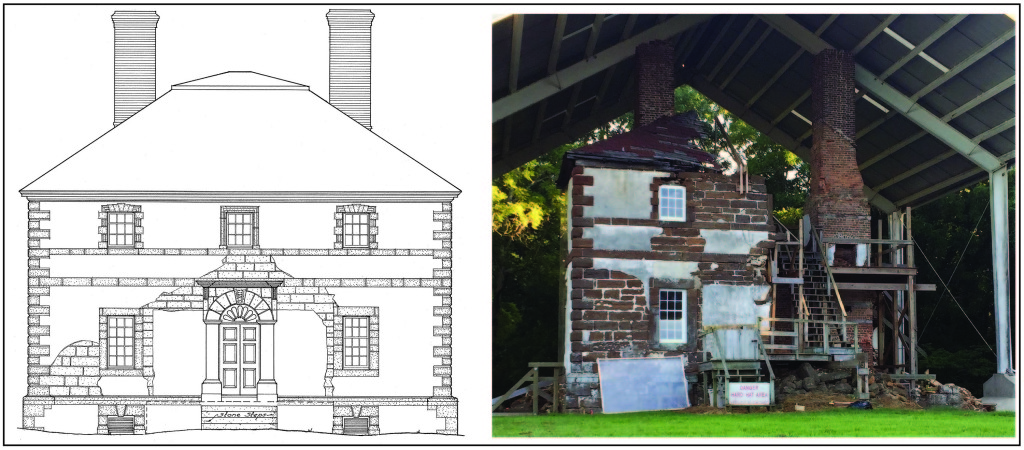

Left: North elevation of Menokin from a 1940 Historic American Building Survey. Right: Modern view of the Menokin ruins under shelter.

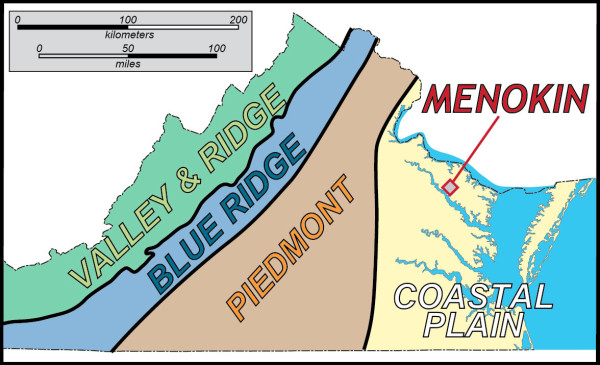

Menokin is built on an upland in the Atlantic Coastal Plain, a region of low topographic relief primarily underlain by sand, clay, and gravel deposited when sea level stood at higher levels than today.

When I first saw Menokin and its large blocks of hewn reddish brown sandstone, I was puzzled as to the source of the stone. In eastern Virginia stone houses are rare. Important colonial buildings in the Tidewater region are primarily constructed of brick. This makes sense, as the Atlantic Coastal Plain is rich with sand and clay, the main ingredients in bricks, and rocks are rare on the Coastal Plain.

Reputedly, Menokin was constructed from locally quarried stone that archaeologists refer to as the Choptank Sandstone. The Choptank Formation is a geologic unit first recognized in cliffs along the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay in southern Maryland. It’s a Miocene deposit of sand and mud that’s commonly chock-full of marine fossils. The Choptank Formation is not typically lithified, consisting usually of unconsolidated sediment- sand and mud rather than sandstone or mudstone. I examined recent drill logs from Richmond County, where Menokin is located, and lithified layers are not reported in the subsurface.

With this in mind, I thought Menokin would make an excellent venue for my Geologic Field Methods class to study. At Menokin we will try to determine:

- the depositional environment and geologic origin of the sandstone

- the location from which the stone was quarried

- where the sandstone fits in the regional geologic setting

On a mid-November Saturday the William & Mary geologists descended upon Menokin – Rabble with a Cause.

Our first task was to describe the sandstone. Much of the rock rubble from the collapsed house was sorted and cataloged and resides in bins near the Martin Kirwan King Conservation and Visitors Center; this stone will be used in the reconstruction effort.

Menokin is constructed from a ferruginous coarse-grained sandstone and conglomerate. It’s a clast-supported rock that is poorly cemented and relatively porous. The clasts are subangular to sub-rounded, and composed primarily of quartz (including gray, white, and blue varieties) with lesser amounts of feldspar and rock fragments. The cement is a mixture of reddish-brown hydrated iron-oxides. Primary depositional structures, such as planar beds and cross-bedding, are common.

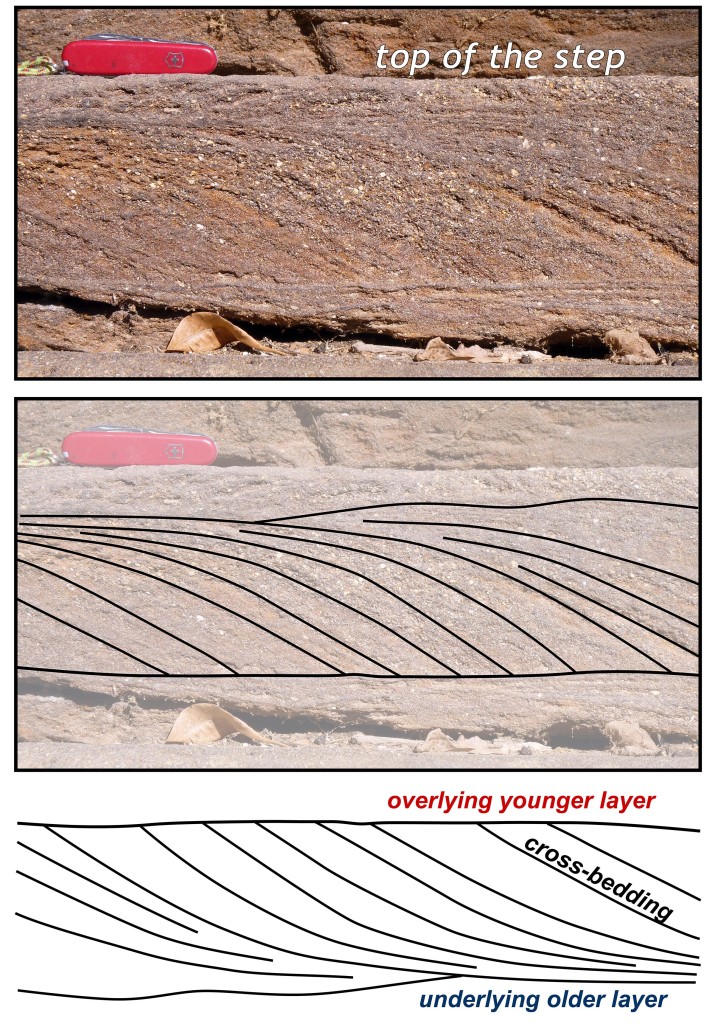

Cut block of sandstone that forms steps at the south entrance of Menokin. Note the well-developed cross-bedding and stratification (traced in the center image). The stone was laid ‘upside down’ such that the top of the stone block is the underlying older layer of sandstone. The bottom image shows the strata in their original ‘rightway up’ orientation. The cross-beds formed as flowing water transported sand (from left to right in the lower image) over a ripple.

We debated the depositional setting for these coarse-grained and somewhat immature sands– is this a shallow marine deposit or a fluvial deposit? We discussed what is necessary for ferruginous sandstone to occur. Iron must first be dissolved in groundwater and then precipitated to form the iron-rich cement that encases the sand grains. What chemical conditions are required to dissolve and then precipitate iron?

We concluded that the Menokin sandstone is not a marine sediment; rather, its subangular texture, mineral composition, and sedimentary structures point to deposition by vigorously flowing water in a stream or river (a fluvial environment).

We’re also confident that the sandstone at Menokin is not from the Choptank Formation. The Choptank Formation is a marine deposit that was laid down in a shallow sea approximately 11 million years ago, at a time when sea level stood perhaps 100 meters (330’) higher than today. During Choptank time the Atlantic shoreline lay to the west of Fredericksburg, and Menokin was a watery place located some 80 km (50 miles) seaward from the coast. The Menokin sandstone was likely deposited during a low stand of sea level when the Virginia Coastal Plain was emergent, and streams carrying their sediment load from the Blue Ridge highlands meandered across the landscape. As sea level later rose, these fluvial deposits were buried beneath a sequence of estuarine and ultimately marine sediments.

Menokin, and the remains of its northern elevation. Preservation architect John Fidler (with the white hard hat) discusses the Menokin ruins and restoration project.

Preservation architect John Fidler gave us a grand tour of Menokin, highlighting its architectural elements such as the ashlar blocks, quoins, and water table stone. Ultimately, Menokin will be partially rebuilt and partially encased in structural glass that will provide a unique perspective on its Colonial architecture. As the existing stone is not sufficient to complete the planned restoration, John would like to find the source of the sandstone.

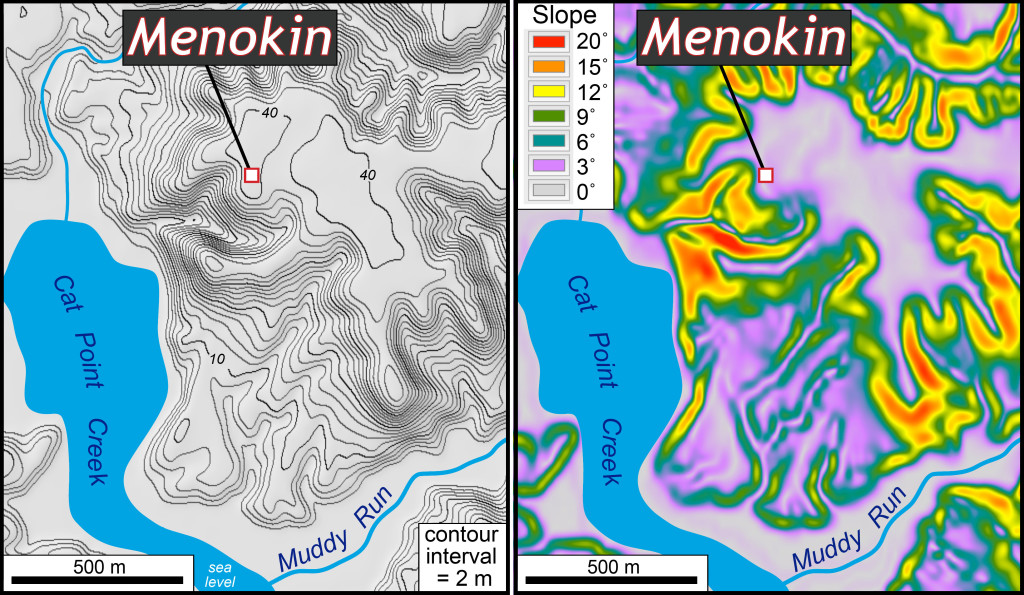

Menokin sits atop a flat upland, ~40 m above sea level, that is being dissected and eroded by small streams that cut steep valleys to nearby Cat Point Creek at sea level. The slopes in some of these ravines exceed 30 degrees, it’s hard to stand upright on these slopes.

Left: Topographic map of the Menokin area. Note the flat upland at ~40 m (130’). Right: Slope map of the Menokin area. The gray-purple areas are flat terrain, while the orange-red areas are steep slopes.

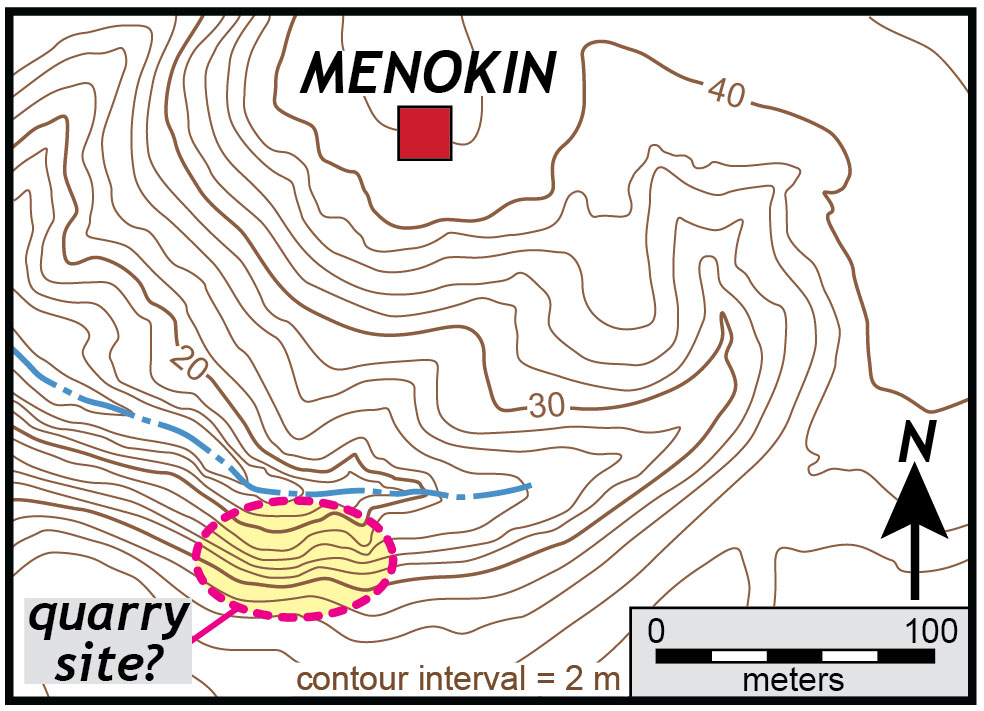

In one of the ravines to the south of Menokin we encountered large blocks of ferruginous sandstone on the slope and in low mounds–could this be an old quarry site? We never located any sandstone outcrop, just loose pieces (in the geologic parlance it’s known as float). Nevertheless, it’s worth further investigation; on future visits to Menokin we’ll auger and core through the sediment layers.

Detailed contour map of the area to the south of Menokin that may include the location of an old quarry site. Map prepared by W&M Research Fellow Megan Flansburg, based on LIDAR data.

In the late afternoon we visited Mount Airy Plantation, a neo-Palladian style house built in 1764 by Colonel John Tayloe II (Rebecca Tayloe Lee’s father). Mount Airy’s been in the same family since the 18th Century; Catherine and Tayloe Emery graciously hosted us, showing off both the house and property.

West corner of Mount Airy, note the large reddish sandstone blocks as well as the white Aquia Sandstone blocks in the quoins, water table stone, and around the window. This house was built in 1764.

Mount Airy is an impressive house; it’s constructed primarily from a ferruginous sandstone and accented with white Aquia Sandstone, a Cretaceous unit quarried near Aquia Creek in northern Virginia. The massive red sandstone at Mount Airy is similar to the stone at Menokin, although it’s of more uniform character and a finer grain size. Colonel Tayloe provided the land and financed the construction of Menokin for his daughter and son-in-law. Some have suggested that the stone used at Menokin was quarried at Mount Airy.

We explored a broad ravine to the northwest of the house and discovered low ledges of ferruginous sandstone, as well as tool marks indicating that the stone had been worked. This might well be the quarry from which the Mount Airy stone was extracted.

Our field day at Menokin was rewarding, but we’ll be back, as there is more still to discover. Genevieve Brei (’17) is continuing this research for her senior thesis; she plans on determining the physical and chemical processes responsible for transforming the sands into sandstone and elucidating just when the sand became sandstone (i.e. the timing of cementation). We’ve also yet to ascertain the specific geologic unit from which the Menokin sandstone is derived.

I’m looking forward to collaborating with Genevieve and the Menokin Foundation to tell the geologic story of this curious sandstone, and its intersection with 18th Century architecture in Colonial America.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.

With my heart pumping with a minor in Geology (University of Missouri-Rolla, now MS&T; major in Metallurgical Engineering) and Tayloe blood coursing through my veins, this research and discovery is amazing and wonderful to read, as to acquire more knowledge of both the geology of the area and of these historic structures, along with helping to paint deeper & more vidid colors into the past. Looking forward to further investigations.

What an exciting mystery! It will be interesting to learn more about when and how this rock formed from Genevieve. Since rock is uncommon in the coastal plain what was different about the depositional environment that caused ferruginous cement and lithification of the coarse grain fluvial sediment to occur?

I’m very interested in seeing where this goes. I frequently encountered similar chunks of sandstone embedded in Miocene deposits at nearby Westmoreland State Park (also home to some marvelous fossilized sharks’ teeth) and have wondered about its origin.