The Soapstone Special

Gabe Mojica ’21

Soapstone. What is it you might ask? No, it isn’t used for bathing, or at least not in the way you might imagine. Soapstone is a metamorphic rock that is composed primarily of the mineral talc – one of the softest minerals in the world. Soapstone’s softness allows it to be easily carved and shaped. This paired with its unique thermal properties and appealing look, make soapstone desirable for architectural and commercial uses. Soapstone has been carved by native peoples since prehistory, who used it for bowls, pipes, and statuary.

Figure 1. A large art deco eagle sculpted from Virginia soapstone that stands near the entrance to the Johnstown, Pennsylvania post office. Photo by Michael Minn.

In the late 19th century, the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in central Virginia became the center of America’s soapstone quarrying industry. In 1883, James Serene and several partners bought a 1,955-acre plot of land known as Beaver Dam Farm in Albemarle County, Virginia, which quickly became the Albemarle Soapstone Company. However, to give their stone a distinct identity, Daniel Carroll (one of Serene’s business partners) had the idea to rename the company Alberene Stone, a portmanteau combination of Albemarle and Serene; very original. This company flourished in the soapstone market, making countertops and benches for laboratories and hospitals, thermal insulators, doorknobs, pots, pans, and yes, even sinks and bathtubs.

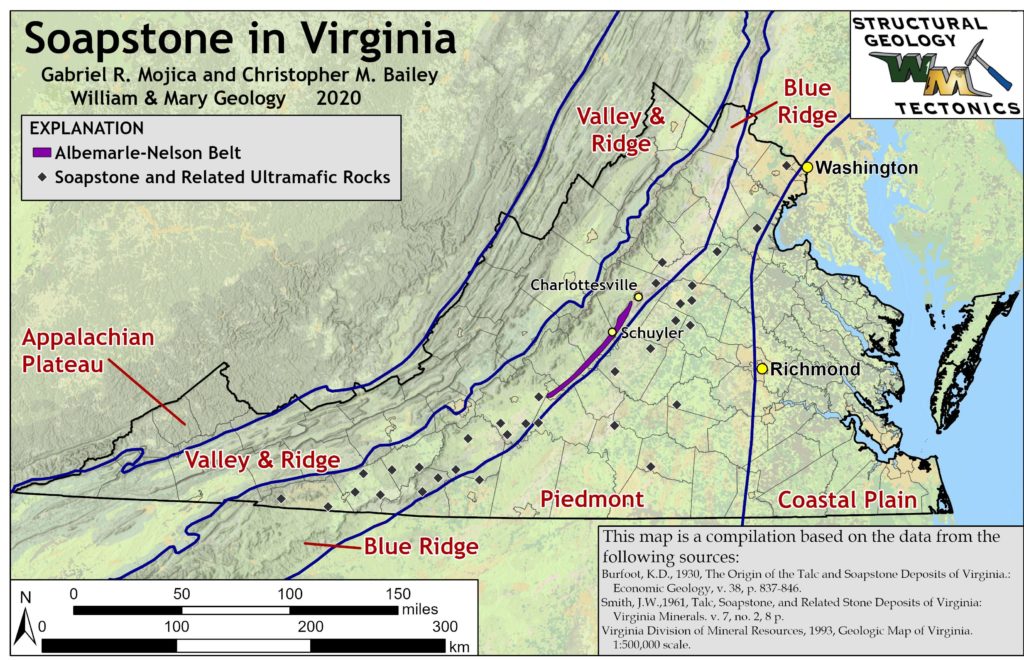

In Virginia, soapstone used to be a big deal. By the early 1900s the town of Schuyler, on the Albemarle-Nelson county line, had become the capital of soapstone. In 1922, the soapstone industry was booming as Alberene Stone had its biggest year yet, grossing more than 1.5 million dollars, and employing more than 1,500 workers. However, all good things must come to an end, and in the post-World War II years demand for soapstone declined with the innovation of cheaper petroleum-derived products.

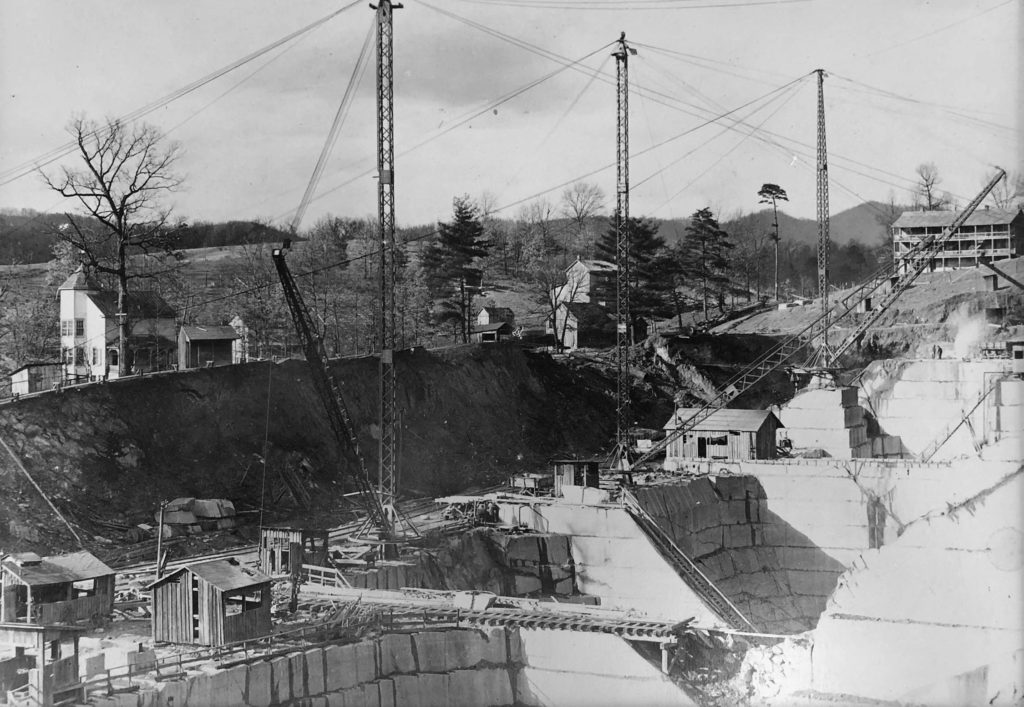

Figure 3. Old school view of soapstone quarries at Schuyler, Virginia from the early 20th century. Photo courtesy of Candice Clark, Polycor Inc.

In the 2010s, Polycor Inc., a dimension stone producer based out of Canada, restarted quarrying activities near Schuyler. They quarry large blocks which are then slabbed to make high-end kitchen countertops and other architectural uses. Today, Alberene Stone is the only soapstone produced in North America.

Figure 4. Virginia soapstone kitchen island (top) and sink (bottom). Images from: kitchen island and sink.

Let’s discuss the geology of Virginia soapstone. As previously mentioned, soapstone is a metamorphosed rock that originated as an igneous rock. Its protolith (the original rock) was likely an ultramafic rock such as a peridotite, which makes up much of the earth’s upper mantle. Ultramafic rocks are extremely dense and don’t typically occur in the less dense continental crust. So how does this ultramafic rock get in the Earth’s crust of central Virginia? At some point, likely long after the igneous rock formed, metamorphism ushered in a set of chemical and mineralogical changes that transformed the peridotite to soapstone.

My senior research is focused on understanding the structural geometry of the soapstone bodies. Ultimately, we aim to determine when both the protolith crystallized and the soapstone itself actually formed. I hypothesize that these rocks were emplaced as intrusive sills or perhaps lopoliths during a late phase of rifting that broke apart the Rodinian supercontinent and created the Iapetus Ocean (570 to 550 million years ago).

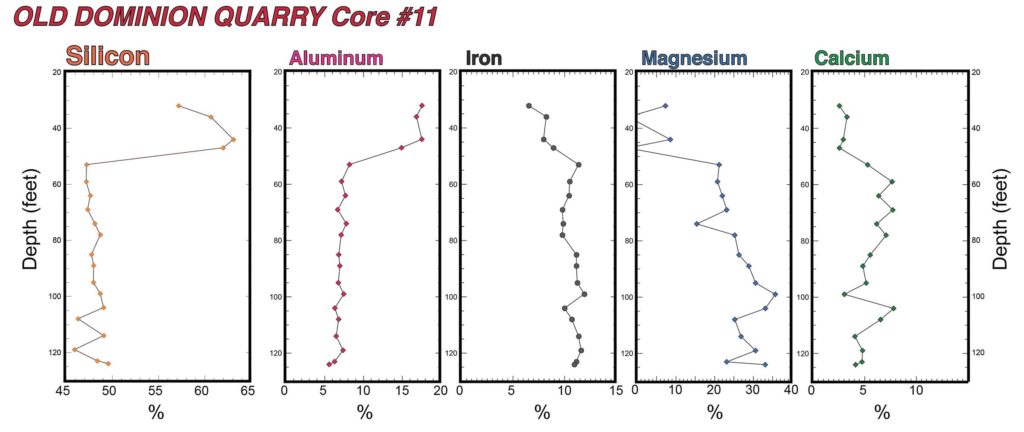

In June 2020, I made the first of my trips to quarries at and near Schuyler. We returned in late August to describe and log rock core drilled at one of the quarries. The logging process is a group endeavor, made all-the-more difficult by our COVID-19 protocols. First, we took notes on the rock’s color, texture, and mineralogy. Additionally, we used a portable X-Ray Fluorescence Analyzer (XRF) to determine the chemical composition of the rock core at ten-foot (3 m) intervals. With these data I’m looking for chemical trends that indicate magmatic differentiation, which would support my hypothesis of this body originating as a sill. In November, we’ll be back at Schuyler to log more rock core, as Polycor starts a new exploratory drilling program. These cores will provide a unique opportunity to examine the soapstone body from top to bottom. Hopefully, our work will help delineate possible soapstone resources for further expansion.

Figure 6. XRF chemical data for Si, Al, Fe, Mg, and Ca from a rock core drilled into a soapstone body near Schuyler, Virginia.

If you told me four years ago that I would be a geology major, I wouldn’t have believed you. I originally took geology as a placeholder class. But both the subject matter and dynamic environment in the W&M Geology department were like no other, and from there I was hooked. Now, I’m conducting original research and collaborating with Polycor to better understand a unique and historic mineral deposit – it’s a cool capstone to my William & Mary experience.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.

Great work, Gabe! I’m incredibly grateful to witness your hard work and so happy to see it come to fruition. Keep it up!

Wow, could you tell us more about the thermal properties of soapstone?

You did a great job! Such an interesting blog post!

Very nice

An excellent blog with an excellent map