Field Methods 2014: Wrapping It Up

The last day of classes at William & Mary is traditionally a celebratory affair, and on the last day of class this fall we wrapped up the Field Methods course with a rowdy poster session where the results from our three field projects were presented.

As I noted earlier this semester, Geology 311- Field Methods in the Earth Sciences (pdf) is a class in which students do geology in the field while conducting original research to better understand the geology and landscape history at three different locales across Virginia.

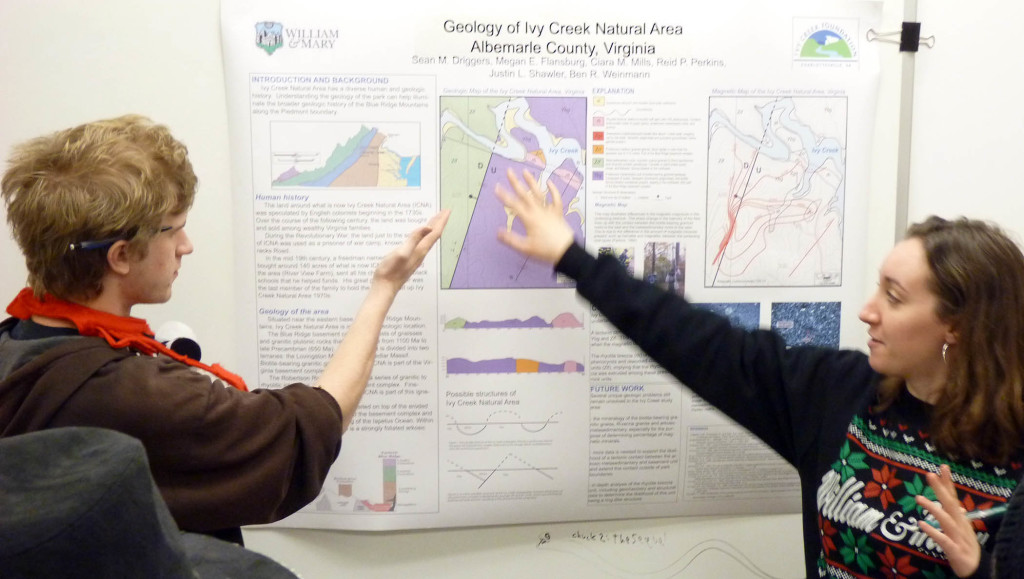

W&M Geology majors Reid Perkins and Ciara Mills have an animated and arm-waving discussion regarding their Field Methods research poster.

Rick Berquist (in the hard hat) has the Field Methods students mesmerized as they discuss sediment at the North Anna Battlefield Park.

During the semester we made four trips to the North Anna Battlefield Park, where 150 years earlier the Union and Confederate armies clashed in May 1864. The Confederate troops occupied entrenched positions on the sand and gravel deposits that cap the uplands. The southbound Union army had to cross the steeply incised valley of the North Anna River and then ascend steep terrain directly into the maw of the Confederate position with predictably gruesome results.

Our fieldwork better located the Fork Church fault and revealed four sets of incised sand and gravel deposits. With the help of Rick Berquist, Marcie Occhi, and the Virginia Division of Geology and Mineral Resources’ drill rig we obtained a 15 m (46’) core through the blanket of upland sediment and into the 5 to 7 million year old silty clay of the Eastover Formation. During the late Miocene the Atlantic Ocean reached this far inland.

On a gray and windy Saturday morning we descended upon the Ivy Creek Natural Area, a 215-acre preserve just north of Charlottesville, and met up with a group of Ivy Creek naturalists who gave us a gracious introduction to the preserve. My mother, a Charlottesville naturalist and native, made a timely delivery of pumpkin bread that preserved group morale. During the day we mapped the underlying bedrock and completed a magnetic survey. There’s some interesting geology at Ivy Creek; at the north end of the park a clast-rich rhyolite dike (possibly a volcanic ring dike) cuts the older basement rocks, and in all my years of examining Virginia’s geology I’ve never seen a volcanic rock that looks so young. At the park’s western edge arkosic metasandstones are strongly deformed and hint that there might be a tectonic boundary hidden in the subsurface.

Who can forget our late September foray to the Piney River (hineys in the Piney)? We returned on a brisk, but brilliant November day to finish mapping the geology along the Blue Ridge Railway Trail. At the trail’s western end we encountered anorthosite, a rare feldspar-rich igneous rock that was once mined for titanium in the Piney River area. Some 30 to 40 years after mining has ceased the environmental damage caused by the operation has mostly healed.

Classes are done, final exams are upon us, and I’ve got a pile of field books left to grade. One final semester task that remains for the junior geology majors is narrowing down a topic for their senior research projects. I hope that our field projects at North Anna, Ivy Creek, and Piney River whetted some geologic appetites for future geological research.

No comments.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.