Battling Boreas

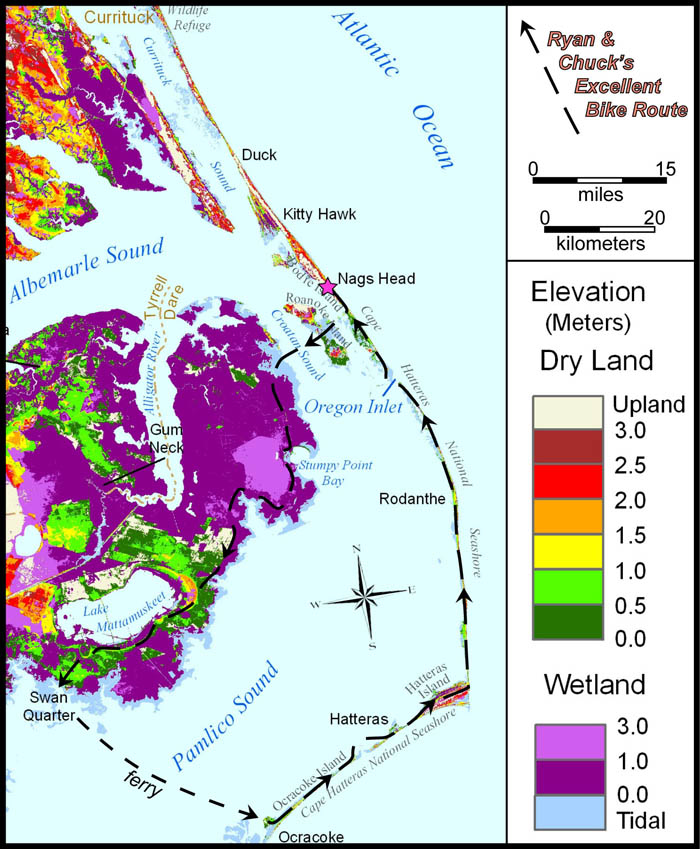

Elevation map of northeastern North Carolina and the Outer Banks with our bike route illustrated. Map modified from Titus and Wang (2008). Select image to view original.

William & Mary is in the midst of its Spring Break and many students have departed for destinations where learning, service, and leisure are on the menu. Professors also need a break from campus and many take their leave of Williamsburg during this week with no classes. I got away from campus with my colleague and fellow structural geologist Ryan Thigpen, we decided that a big loop ride around eastern North Carolina and the Outer Banks on our road bikes was the perfect ticket for Spring Break fun. We drove to Nags Head with the plan of riding 75 miles southwest to Swanquarter then taking the ferry to Ocracoke Island, and on the second day we’d ride from Ocracoke to Hatteras, north along the barrier island back to Nags Head, another 75 miles. During the week we watched the forecast, hoping the nasty winter would loosen its grip and let us roll easily through coastal Carolina. High pressure was in the forecast. High pressure- the bringer of clear and dry skies- things looked good.

The Man in Black, Professor Ryan Thigpen.

Friday dawned cool and clear. Suitably attired in spandex tights and windproof riding booties we saddled our bikes and pedaled into the new day. At Whalebone Junction we left the Outer Banks turning west to Roanoke Island, a short crossing of the island put us on the U.S. Route 64 bridge and squarely pointed towards the mainland. The bridge spans 4 miles of Croatan Sound and it was here that we were first introduced to Boreas, that ill-tempered Greek god of the north wind, blowing at 15 miles per hour and with plenty of fetch over the open water. Boreas served up a quartering headwind, a noticeable impediment to our progress, but no big deal. We rolled onto the mainland and soon turned southward through the Alligator River lowlands; now the wind was at our backs and the miles clicked off quickly and efficiently. Into the town of Engelhard for lunch, where we ate fish sandwiches on the dock while locals gave the two dudes in bike tights a wide berth. By 2 p.m., with 75 miles of asphalt behind us, we were at the ferry landing in Swanquarter; unfortunately the Ocracoke ferry departs at 5 p.m. Swanquarter is pleasant enough, but a challenging place to while away an afternoon. The ferry departed on time and plied its southeasterly course across Pamlico Sound. We landed on Ocracoke in the dark and with headlamps ablaze pedaled the last mile to our motel. Ocracoke had yet to awake from its winter slumber, but with effort we discovered that beer and pizza were to be had on the island.

Crossing Pamlico Sound en route from Swanquarter to Ocracoke.

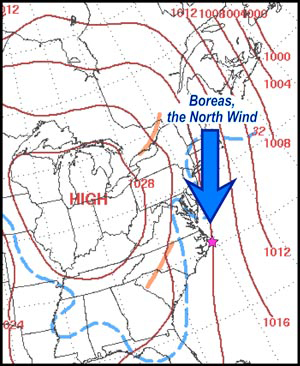

Annotated synoptic weather map of eastern North America for 7 a.m. (EST) March 6, 2010. Dashed blue line is 32˚ F (0˚ C). Reddish-brown lines are isobars, lines of equal atmospheric pressure.

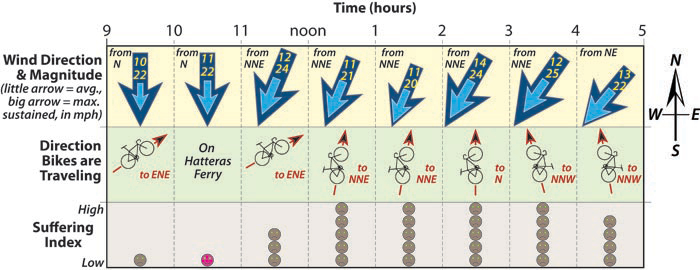

Saturday morning was bright and cold; the wind had an edge that was missing the day before. The high-pressure system was still situated over the Midwest and its clockwise flow of air continued to bring a north wind to the Outer Banks. The first leg was an east-northeasterly traverse of Ocracoke Island to the Hatteras Ferry. Boreas blew a quartering headwind on our left flank. While waiting to board the ferry Boreas chilled us, while on the ferry our fellow passengers shook their collective heads at our gambit. We rolled off the ferry in Hatteras on a downwind leg that was every bit of 100 yards long- then the road veered sharply left and we confronted the headwind. The ride from Hatteras to Frisco to Buxton was by no means fast, but forest and dune provided some shelter from Boreas.

At Buxton, Hatteras Island makes a pronounced dogleg and our course changed from northeasterly to northerly. Boreas was bringing his A game now- a full frontal headwind blowing with sustained winds of over 20 mph. There was nowhere to hide, we both pulled at the front and took turns tucked in behind the lead rider. Two riders don’t make a pelaton. It was hard riding and our speed sagged. Hatteras Island is a low barrier island- mile after mile of sand and spartan vegetation surrounded by salt water- no shelter from the storm here. We crawled slowly northward, first into Avon and later Rodanthe. We had to keep the proper perspective-we were doing this for fun, right? In the Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, sand and standing water were both bounding across the road. Boreas kept blowing- the suffering index was high.

Overview diagram of wind direction and magnitude, direction of our bikes, and suffering index plotted against time during the bike ride from Ocracoke to Nags Head, North Carolina on Saturday, March 6, 2010. Wind data from the Billy Mitchell airport, Hatteras Island.

Slow progress took us ever northward on North Carolina Route 12. As we approached Oregon Inlet and the 3-mile crossing over a high bridge, the sense of weariness and dread were consuming. Yet, the actual experience was sublime- a panorama of sky and sea with a wind that began to angle in from the northeast, offering us a needed respite. We eased into bigger gears as we pedaled onto Bodie Island, our workload slackened yet the pace picked up. We rolled into Nags Head windburned and sore, happy to have our 155-mile loop finished.

Last March I wrote a piece entitled Spring Break Sunshine, I was tempted to entitle this post Spring Break Stupidity, not solely as a tribute to our ill-timed bike ride, but also to highlight other human follies on barrier islands. Over the last 50 years large tracts of the Outer Banks have been developed; countless vacation homes for the well-to-do are built just behind the dunes. Barrier islands are dynamic environments, wind and water moves sediment, storms erode beaches and opens inlets. As the nor’easter (Nor-Ida in this case) of November 2009 demonstrated, human structures are vulnerable. Millions of dollars per year are spent to keep North Carolina Route 12 and its bridges open. Who pays that bill?

Left- The foam flies as waves cut thru the dunes while the North Carolina Department of Transportation attempts to shore up North Carolina Route 12 near Rodanthe during “Nor-Ida”, November 12th, 2009 (photo by Steve Earley, The Virginian-Pilot, http://hamptonroads.com/2009/11/photos-november-09-noreaster-outer-banks). Right- Atlantic Ocean waves beneath cottages in south Nags Head, North Carolina, November 13th, 2009 (http://camalines.files.wordpress.com/2009/11/nov09storm1.jpg)

High water and wind make for plenty of drama, but there is a longer-term problem. As the Titus and Wang map (top figure) so colorfully illustrates much of the Outer Banks and eastern North Carolina is less than a meter (~3 feet) above of sea level. Like it or not sea level is rising, during the 21st century great swathes of the region will be affected by sea level rise. Locations in the greens and purples are likely to become watery in the next two generations. How shall we ‘protect’ the shoreline? In their unfettered state barrier islands, gossamer as they are, move landward or seaward in accord with the rise and fall of sea level. But what is to be done when expensive homes, shopping centers, and golf courses are affixed to the islands? Seawalls and hard revetments protect property but destroy beaches- the very object that brings many of us to the shore. Dealing with coastal erosion is expensive. Who will pay the bill?

A short blog piece is no place to properly frame the consequences of sea level rise, shoreline erosion, and coastal hazards. For a thoughtful and, for some, alarming discussion read The Rising Sea by Orin Pilkey and Rob Young (W&M Geology class of 1987). Our Spring Break battle with Boreas was a bracing but beautiful adventure. The struggle with the rising sea will be a truly epic and consuming challenge for humanity.

The Rising Sea can be previewed at http://books.google.com/books?id=U4JV91-gZZUC&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+Rising+Sea&cd=1#v=onepage&q&f=false

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.

Stupid headwinds…making life difficult! But We think people should still be able to build houses on the Outer Banks so long as they are off the hundred year flood plain! (Safe enough perhaps?)

Sincerely,

the WM freshman 😉