A Frenzy of Fall Field Trips 3: Going to the South Side

Moby, the American musician with a wide-ranging and stylishly downtempo sound, released an exceptional album entitled Play in 1999. My favorite song is South Side, here’s a short snippet of the lyrics

… we ride all day

looking out for a sunny day

here we are now going to the South Side

Two decades later, the 2019 William & Mary Geology Fall Field trip rode all day looking for a sunny day and headed to the South Side – Southside Virginia that is for a field excursion that combined learning and fun.

Southside Virginia is a geographic region whose boundaries are not precisely defined. It encompasses the Piedmont province to the south of the James River, and from the Fall Zone in the east to nearly the Blue Ridge Mountains in the west. In the Colonial era, the Southside was Virginia’s first frontier as English settlement spread west from the Coastal Plain. Today it’s a rural region with a smattering of small towns and cities. It was once a major tobacco growing region, but the number of acres under cultivation has steadily declined since the 1970s, and much of the agricultural land has reverted to woodlands. The region’s manufacturing jobs have pretty much vanished, and consequently the modern population of Southside Virginia is approximately what it was in the mid-20th century.

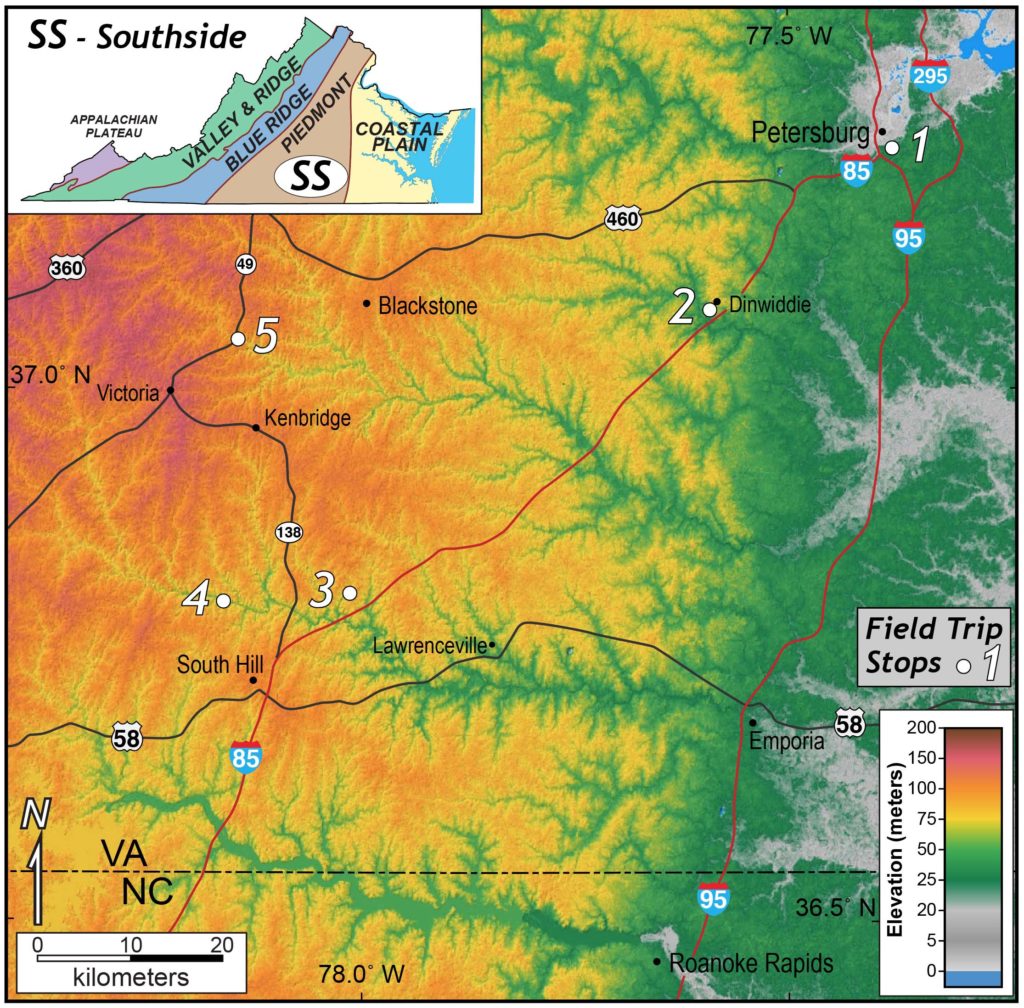

Shaded relief map of the Southside Virginia Piedmont (modified from Owens and Bailey, 2018).

Beneath this broad expanse of monotonous topography and thick soil is a complex, but wondrous, suite of bedrock. Professor Brent Owens and his students have doggedly worked to understand the enigmatic geology in this corner of Virginia for the past two decades. Our 2019 Fall departmental field trip set off to examine the region’s geology, its hydrology, and explore the connections between human history and geology.

At our first stop we circumnavigated the Crater at the Petersburg National Battlefield Park. Here in late July 1864, the Union army set off a mine after tunneling through Coastal Plain sediments and underneath the Confederate lines. What ensued was a terrible slaughter. In 2014, my research students working with Rick Berquist of the Virginia Division of Geology and Mineral Resources studied the geology at the battlefield and determined that the local stratigraphy played a significant role in the tunneling operation and the shape of the blast crater.

In Dinwiddie, we clamored over a whaleback-shaped outcrop of granite. Although, large bedrock outcrops are rare in the Southside Piedmont, at some locations surface processes conspire to create expansive outcrops with plenty to see.

Later in the morning, Geology senior Izzy Muller led us on a short hike into the forest, and amidst a riot of vegetation, she showed the assembled masses’ exposures of the Union Mill gneiss. Izzy’s petrologic and geochemical research is providing new insight into the origin of this enigmatic rock.

We lunched beside the historic Whittles Mill along the Meherrin River. Here we discussed and traced drainage basins/watersheds, and in a time-honored William & Mary geology field trip tradition, we estimated the discharge along the Meherrin. Outcrops along the northern bank of the river superbly expose a suite of younger granitic rocks that intruded into the Union Mill gneiss. Collectively, these rocks were later sheared and deformed as the Panagean supercontinent came together in the late Paleozoic.

Close-up of the outcrop at Whittles Mill. Note the lighter granitic rocks, and darker gray Union Mill gneiss. Both rocks have been strongly deformed.

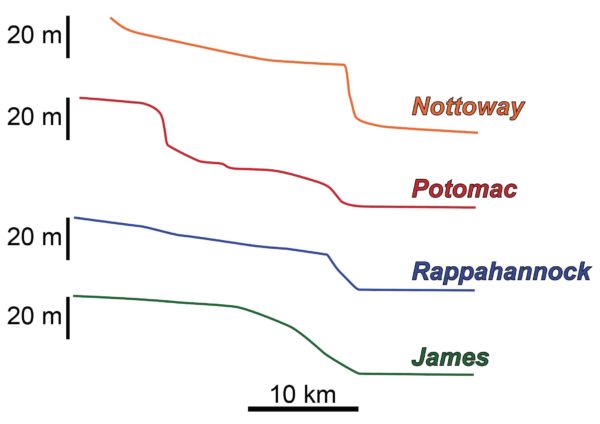

Our final stop at Nottoway Falls commenced with a discussion of why such a large knickpoint occurs here (its total drop is comparable with or larger than more well-known regional knickpoints such as Great Falls along the Potomac or the James River’s drop through the Fall Zone in Richmond).

Nottoway Falls knickpoint compared to other regional knickpoints in the Fall Zone (from Owens and Bailey, 2018).

The Nottoway knickpoint involves a series of cascading drops and pools, thus providing a set of first-rate swimming holes. Many of the W&M crew finished their field day with a well-deserved dip in the river.

For some this will be a one-and-off experience, but for others this trip may be the first of many field experiences with the William & Mary Geology department as we offer trips from the local (College Woods to Jamestown) to the far distant (Bahamas, Hawaii, Norway and Oman). Learning outside the classroom is a big deal, and the Geology department is proud of these unique experiences open to all William & Mary students.

Comments are currently closed. Comments are closed on all posts older than one year, and for those in our archive.

Did you know Gwen Stefani had recorded vocals to be included in “Southside”, but they had to be cut because of production problems? She did make it into the music video. Moby’s pretty good, but I’m more of an Aphex Twin guy myself.

If I had known we were going to a civil war battlefield, I may have woken up in time for the field trip. I had never heard the Civil War story of subterranean sabotage before reading your previous blog-post. My great-great-grandfather fought in JEB Stuart’s cavalry for the entire war. According to family legend, he was quite a mean man, and would regularly threaten to drown his children in the creek. I don’t know what kind of surface process that would be considered? Extended submersion?